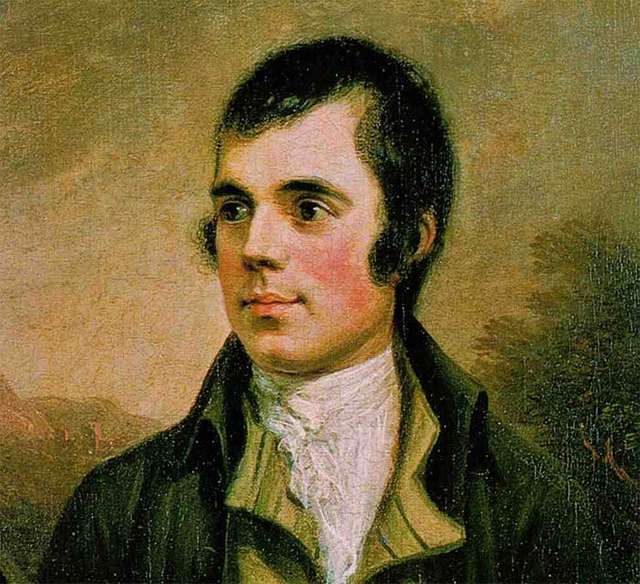

We have recently marked Burns Night, the annual celebration of the life and poetry of Robert Burns (1759-96) held on his birthday, 25 January. The editorial team of CulturAll spent the evening at a restaurant in west London in a diverse group with representation from the United States, Australia, Germany, Mexico and England as well as bonnie Scotland: haggis was consumed, whisky was savoured and verse was recited. If it lacks the frantic energy and commercial might of St Patrick’s Day, Burns Night is an occasion on which everyone can be a little bit Scottish.

The birth of a tradition

The Burns supper, for all that it is milked for its financial opportunities, is an authentic tradition. The first was held on 21 July 1801, the fifth anniversary of the poet’s early death aged only 37: nine of Burns’s friends gathered in the cottage in Alloway in which he had been born to remember him and his work. Led by the Reverend Hamilton Paul, they ate haggis and sheep’s head, recited his Address to a Haggis, a good-natured and richly demotic paean to offal, and sang some of his popular songs. It is a fair assumption that, as the prim phrase has it, “drink was taken”.

If Burns’s friends were loyal, they were not as organised as they could be. Deciding to meet again on his birthday, they got the date wrong and gathered on 29 January 1802, and it was not until the following year that they celebrated Burns Night on the date we now mark. But they had set in motion something which proved popular; the same night as their first dinner, the Greenock Burns Club and Ayrshire Society was founded at the Henry Bell Tavern in Greenock. It survives to this day and is known as “The Mother Club”, with a network of more than 250 similar clubs around the world, not only in Britain but as far afield as Atlanta and Winnipeg. Where the Scots diaspora has gone, Burns often follows in its footsteps.

For some, this curation of the poet’s legacy is a profoundly serious business. There is a Robert Burns World Federation, founded in 1885, which not only links Burns Clubs across the globe but provides a network for serious academic scholarship and more generally the promotion of Scots culture and literature. At the same time, Burns Night is for many, especially those in whose veins Scottish blood runs relatively diluted, an opportunity for a slightly offbeat but entertaining occasion.

Kilts are pulled from the darker recesses of wardrobes, those who normally would not choose to drink it will theatrically accept a “dram” (or more) of whisky and ripely overdone Scottish brogues will be adopted to declaim the set-piece verses like the Selkirk Grace and the Address to a Haggis. Afterwards chosen loquacious guests will deliver “the Immortal Memory”, a speech touching on some aspect of Burns’s life or work, followed by the Address to the Lassies, a light-hearted thanks to the women who have supposedly been responsible for providing the food and drink. A female guest will respond with an equally jocular Reply to the Laddies. Generally there is then a free-for-all for anyone who wants to recite a poem or even sing one of Burns’s songs put to music.

The formulaic nature of a Burns Night is not unlike a wedding. There is an accepted framework, a general sense of wellbeing and good wishes, an opportunity to dress up and a tacit licence to overindulge. The timing of the celebration is fortuitous, too. By the time of Burns Night, Christmas is a full month in the past, New Year’s Eve & Hogmanay have been and gone, leaving many of us with a determination to be better or healthier or more virtuous in some other way. But reality is beginning to assert itself and January is a month of cold, dark consequences for festive gluttony and luxuriousness. We can be forgiven for seizing a chance to break the monotony of virtue.

Burns and the shaping of Scottish identity

I have a sense, purely anecdotal and instinctive, that celebrating Burns Night has become more popular and more prominent since my childhood. Neither of my Scottish parents would have made any effort to do so, though my father, a psychologist, felt no urge towards poetry of any kind, while my mother, an English teacher, vigorously disliked Scotland and Scottishness and never regretted leaving the country in her 20s.

Now, however, London will offer myriad outlets for any desire to remember the Ploughman Poet, the Bard of Ayrshire and Scotland’s favourite son. There is no doubt a potent commercial drive: anything that can be packaged and marketed will fall into the hands of the hospitality industry. St George’s Day, once a national feast on a par with Christmas for mediaeval Englishmen and women, provokes annual controversy and introspection but is increasingly marked in some way; Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party wanted 23 April to be a public holiday, which is a sure sign of progressive acceptance.

Scottish identity is changing too, in ways which are good and bad. Last year marked the 25th anniversary of the creation of the Scottish Parliament, and it is worth remembering that when the assembly was officially opened on 1 July 1999 by Queen Elizabeth II, the traditional singer Sheena Wellington gave a rendition of Burns’s A Man’s a Man for A’ That as part of the ceremony.

The song’s defiant egalitarianism found resonance with New Labour and with the Scottish National Party, seeming to set the nation itself up as a champion of equality and fairness. It would be performed again 18 months later in Glasgow Cathedral at the funeral of Donald Dewar, the inaugural First Minister of Scotland, and rock veteran Midge Ure revived it for the opening of the fifth session of the Parliament in July 2016.

A romantic rogue, or beyond the Pale?

It is only fair to say that the dewy-eyed and uncritical adoration of Burns is easy to mock. He lived a short, rackety and often impecunious life, and his romantic and sexual exploits were often messy and unthinkingly unkind. Although preparing formally to marry Jean Armour, by whom he had already fathered four children and then abandoned, he had a passionate but unconsummated affair with Agnes Maclehose, known as Nancy, in 1787/88. They exchanged fiercely emotional letters and poems, which did not prevent Burns from fathering a child by Nancy’s maid.

Burns and Nancy met again after his marriage, in Edinburgh on 6 December 1791. It would be their last encounter: although Burns would be dead within five years, Nancy lived until 1841. In her diary on that date, she wrote:

“This day I can never forget. Parted with Burns, in the year 1791, never more to meet in this world. Oh, may we meet in Heaven!”

The parting does not seem to have affected the poet quite as deeply.

Inevitably, given the tenor of our age, there is also controversy attached to Burns over the issue of slavery. In 1786, short of money as he frequently was, he accepted a position as “book-keeper” at the Ayr Mount sugar plantation in Jamaica. It was owned by Dr Patrick Douglas of Garrallan near New Cumnock but managed in person by his brother Charles. Although the post was framed as an administrative one, it would also have required Burns to act as an overseer of the slaves working in the fields (he described it as being a “poor Negro driver”).

Burns never went to Jamaica. Two ships on which he was scheduled to travel sailed without him as he found the prospect less and less appetising, but he was saved by the sudden, unexpected and considerable financial success of a collection of his work entitled Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (known because of its place of publication as “the Kilmarnock volume”). It was well received critically and made Burns a national figure, but it also gave him the financial stability to abandon the job in Jamaica.

For some, the fact that Burns even contemplated accepting employment in the sugar industry is damning, reliant as it was on slavery. One academic noted with distaste that Burns was “strangely silent on the question of chattel slavery compared to other contemporary poets” and that his name nowhere appears on any petition in favour of the abolition of slavery. She did allow that there might have been mitigating circumstances, but added that his supposed authorship of The Slave’s Lament (1792), an empathetic treatment of the misery of slavery, is now questioned.

Placing an 18th-century figure beyond the pale for his perceived failure to be sufficiently vehement in condemning an economic system that was still hard-wired into Britain’s place in the world may seem unduly and unreasonably harsh to apologists, but each of us must make our own judgement.

Burns in context: the Scottish Enlightenment

Burns exists in a much broader sense, and it is here that we can appreciate his importance, and perhaps understand his growing appeal. One fundamental element is that Burns’s poetry is often quite staggeringly good. He grew up in back-breaking rural poverty in Ayrshire, his father a self-educated tenant farmer, and the education he received was intermittent and varying. As well as schooling from his father, he spent a few years at an unregulated “adventure school” in Alloway as well as a brief period at the parish school when he was 13 and 14. But by the age of 15 his formal education was more or less over and he was the principal labourer on his family’s 70-acre farm.

This was real intellectual deprivation. It was the time of the Scottish Enlightenment: the country had five universities to England’s two, more accessible that most European institutions and at the cutting edge of many subjects; there was a blossoming of intellectual clubs or salons like the Select Society in Edinburgh and Glasgow’s Political Economy Club, of which Adam Smith was an early member; it was also the era of David Hume, James Boswell, Adam Ferguson, Thomas Reid and Tobias Smollett. There was a heady cultural, literary and scientific milieu, but Burns was not a creature of Edinburgh, the ‘Athens of the North’, or the booming tobacco port of Glasgow, but the rural south-west.

Sir Walter Scott was 16 when he met Burns in the late 1780s. He described the poet’s “manners rustic, not clownish, a sort of dignified plainness and simplicity”, and was impressed by his composure, but it was taken as read that he was an outsider in Scottish high society. Yet Burns was able to draw on an astonishingly broad range of influences, intimately familiar with classical literature, the Bible and the canon of Anglophone writing. He also turned to the Scottish vernacular makar [royal bard] tradition of poetry embodied by people like William Dunbar, Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount and William Drummond of Hawthornden.

The true genius lay in what Burns did with these various strands. Using both Scots and the dialect forms of English spoken in Scotland, he created a body of work which had a spontaneity and directness which no other writer could match, and which encompassed political and philosophical issues, class, gender and socio-economic status, religion, sexuality and the most fundamental emotional and romantic aspects of life.

Burns could be funny, both wry and jocularly crude, as well as bitingly satirical. Tam O’Shanter is a richly comic tale of a drunk making his way home past a haunted church and encountering supernatural visions, while The Holy Fair dissects the human frailties, absurdities and cant on display at a local celebration. There were potent political messages in A Man’s a Man for a’That, Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation and Scots Wha Hae.

It is in his romantic poetry, perhaps, that Burns is at his most intense. I suggested earlier that he had found his parting from Nancy Maclehose easier than she would do, and certainly he had a much shorter life to endure its consequences. But read Ae Fond Kiss, the verse he composed to immortalise their separation, or, better still, listen to it sung by Eddi Reader, Karen Matheson and Paul Brady or Robyn Stapleton. This is heartbreak of an agonising and profound nature, the knowledge that a man and a woman who have an indescribably intense romantic bond will never meet again.

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae fareweel, and then for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

Burns may have been a recklessly affectionate lover and certainly left emotional casualties in his wake. It is impossible to deny, however, the power of his distillation of everything he had read and thought and felt into words which could carry a shattering feeling in a popular and demotic form.

Scotland in transition

We also need to think about Burns in his historical context. He was writing and being published in the 1780s and 1790s, and he was doing so in a distinctively and deliberately Scottish way. This timing is important: as I said earlier, it was the heyday of the Scottish Enlightenment but it was also a period in which Scotland was trying to find a new sense of identity and place in the world.

England and Scotland had been united as Great Britain in 1707—in theory a merger, though for unavoidable reasons of size and wealth, England dominated the new polity as it still does—and the Parliament of Scotland had ceased to exist. (Burns wrote in Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation that the country had been ‘bought and sold for English gold’, a reference to the bribery of Scottish legislators to agree to the Act of Union.) Although 45 MPs sat in the new House of Commons for Scottish constituencies and the peerage of Scotland elected 16 of their number to sit in the House of Lords, political power was now concentrated in London.

The government of Scotland between the union of the crowns in 1603 and the formal Act of Union in 1707 had been very much the junior partner to its English counterpart. Nevertheless, it had maintained a separate existence: a Lord Chancellor, a Privy Council, two Secretaries of State and a Treasurer.

It is true that the Act of Union preserved Scotland’s separate legal and judicial system, so Edinburgh remained home to the College of Justice, comprising the Court of Session under the Lord President, the High Court of Justiciary under the Lord Justice General, the Faculty of Advocates and the Society of Writers to His Majesty’s Signet (the equivalent of English barristers and solicitors). In many ways the legal system became a proxy for a separate political existence, and it is significant that Parliament House on the Royal Mile, where the legislature had sat until 1707, became home to the courts and the Faculty of Advocates.

The Church of Scotland remained a separate institution too. Attempts by James VI & I and Charles I to impose Anglicanism on the kirk had been disastrous and were abandoned, with episcopacy being abolished and a Presbyterian system of governance reaffirmed after 1690. It was acknowledged as the national church, though did not have the established status that the Church of England enjoyed south of the border; nor did it want it. The Church of Scotland was governed by its General Assembly which met every year, presided over by an elected Moderator, while the Crown was represented by the Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly, whose role was, and is, largely ceremonial.

This ambiguity embodied the fact that Scotland was now a nation but not a state, and finding ways to express its identity proved challenging. That became more true after the attempted Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745-46; there were punitive measures against those involved after both insurrections, but those introduced after ‘The Forty-Five’, in the years immediately before Burns’s birth, were especially stringent. The Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746 broke the judicial power of the clan chiefs over their tenants, while the Act of Proscription 1746 increased the penalties for bearing arms in specific parts of Scotland and the Dress Act 1746 restricted the wearing of Highland dress, especially the kilt.

By the fourth quarter of the 18th century, as Burns was flourishing, the intellectual achievements of the Enlightenment did provide some sense of a Scottish identity. David Hume, who died in 1776, was a figure of international stature in terms of philosophy, morals and ethics, while the same year saw the first publication of Kirkcaldy-born Adam Smith’s massively influential Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, a foundational text of modern economics. Scotland also enjoyed a formidable reputation in science, medicine and engineering, as the home of James Ferguson, William Cullen, James Hutton, Joseph Black, James Watt, Francis Masson, John MacAdam, Thomas Telford and William Playfair.

These remained principally the achievements of an urban and property-owning elite. Advances in agricultural and industrial technology were beginning to transform the lives of ordinary men and women, with the Carron Iron Works founded near Falkirk in 1759 and the cotton mills of New Lanark opening in 1786. But Burns did something else, something different. He used his upbringing in rural poverty, a condition common to the vast majority of Scotland’s 1.3 million inhabitants in the mid-18th century, to construct a rich cultural identity which drew on varied sources but was rooted in Scotland and expressed in uniquely Scottish terms. As political autonomy faded from living memory and the trauma of the Jacobite uprisings began to heal—the Act of Proscription was repealed in 1782—a new sense of Scottishness began to emerge, culminating in the pomp and circumstance of George IV’s visit to Scotland in 1822, stage-managed by Sir Walter Scott who had been so struck by his meeting with Burns as a teenager.

The evolution of Scottish identity

Of course this has developed an element of cliché. Some of the features of Burns’s work, the straightforward, generous, romantic and egalitarian sensibilities which run through so many of his poems, are taken as emblematic of an enduring Scottish character. To celebrate Burns Night is to enshrine these as totemic, and Scots happily for a time set aside equally important elements: dour, scolding, often misogynist Presbyterianism, grinding industrial and post-industrial poverty, sectarian hatred and violence, poor public health fuelled by bad diet and substance abuse and an ever-present, lurking, sense of embittered victimhood.

Scotland is not unique in this. Any celebration of national culture and values will always prioritise the good over the bad and minimise uncomfortable historical and social truths, as St Patrick’s Day, the Fourth of July, Australia Day, Victory Day in Russia, Bastille Day and The Twelfth in Northern Ireland amply demonstrate. It may be that this tendency is all the more pronounced when such celebrations take place outside their native land. The narrator of Hugo Rifkind’s recent novel Rabbits, an Edinburgh schoolboy who eventually moves south first to Cambridge as an undergraduate and then to the capital, describes himself eventually as “a London Scot, a Burns Night Scot”. There is something in that, a notion of an identity which is assumed for high days and holy days.

I think we can be too cynical about Burns Night. It is, in its own way, a profoundly Scottish reaction to treat with cynicism a celebration into which we then fling ourselves with uncritical and mawkish enthusiasm, but layers of unfamiliarity, awkwardness, self-conscious irony and retrospective historiographical disapproval cannot obscure the significance of Robert Burns. Despite the international reach of Burns Clubs, it is ambitious to argue that the Ploughman Poet is a figure of the first global rank; any comparison, for example, with Shakespeare is a doomed exercise in folie de grandeur.

On the other hand, Burns was a remarkable, innovative and enduring poet. He sprang from a country which, if counted separately, would still only be something like the 117th largest in the world: Scotland’s population is smaller than that of Paraguay or Togo, less than half that of Belgium. More than 250 years after his birth, he still speaks to the human condition in a universal way, but the context of his life and work also contributed to the shaping of Scotland and Scottishness, squarely in that transitionary period between Scotland’s existence as an independent kingdom and its new status as part of a burgeoning imperial power on which, for a time, the sun would never set.

To be Scottish in the modern world is to owe something to Robert Burns. If he is not an avatar of his nation, nevertheless his work and his way of looking at the world is a thread running through its identity. It seems the least that Scots can do: a warm invitation to friends from beyond Scotland, to spend a cold, dark January evening eating hearty food, taking a glass of whisky and discovering or rediscovering the Bard of Ayrshire.