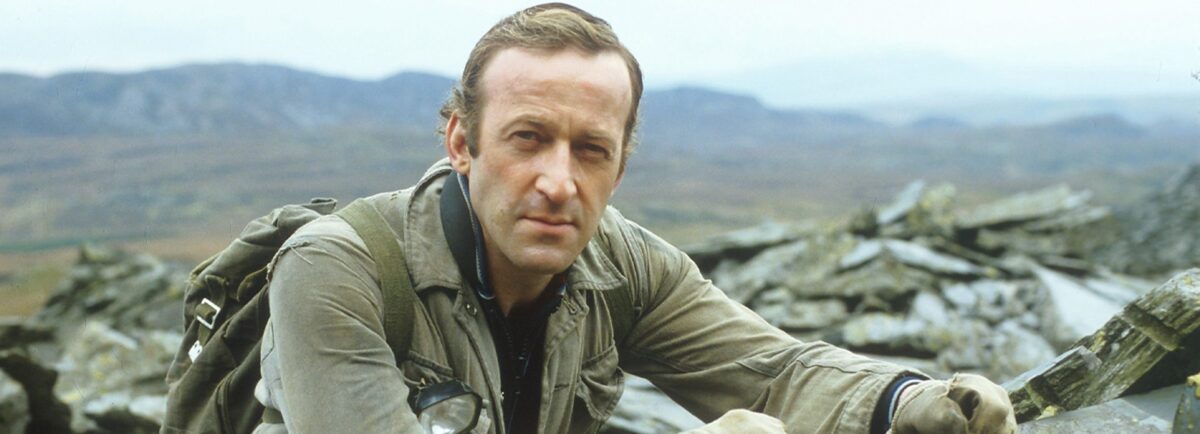

Forty years ago, on Monday 4 November 1985, BBC2 started broadcasting a six-part drama serial called Edge of Darkness. Written by Troy Kennedy Martin, the creator of Z-Cars and writer of Reilly, Ace of Spies and The Italian Job, and directed by Martin Campbell, it starred the 40-year-old Bob Peck as a policeman driven to find the truth behind his daughter’s murder. From that starting point, however, unfurled a dark and convoluted series of shadowy conspiracies and double-dealing in high places, with Peck’s Ronnie Craven driven to dig further and further, whatever the cost.

At the heart of Edge of Darkness was a plot by the nuclear industry, with the complicity of governments in Britain and America, to suppress the work of environmental activists and conceal the intimate relationship between the industry and what we might now think of as ‘the deep state’. Such sinister co-operation was hardly a new trope even 40 years ago, but what Kennedy Martin did so skilfully was to frame a familiar storyline within contemporary fears of corporate power and nuclear energy, use ever-present Cold War fears of nuclear war and bring in James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis.

First formulated in the 1960s, this posited that the Earth was a complex, self-regulating system which acted to sustain life. Named Gaia after the ancient Greek personification of the Earth at the suggestion of novelist William Golding, Lovelock’s idea allowed Kennedy Martin to use nature almost as a character in the drama in its own right. The unseen but pervasive existence of this characterisation was an ingenious counterpoint to the dark forces of government and the agencies of the state, and opened up what could have been an unremarkable story of spies, soldiers and brave idealists into something much more complex, sophisticated and frightening.

Troy Kennedy Martin’s creative and screenwriting credentials were an impressive foundation. Z-Cars, which now seems relatively wholesome and almost quaint, was strikingly innovative when it began in 1962; based in a fictional town in the North West, its specific regional setting, relatively balanced (in the sense of un-fawning) depiction of police officers and its charting of rapidly changing social attitudes broke much new ground. He had also written for The Sweeney, the gritty mid-1970s Flying Squad drama created by his brother, Ian Kennedy Martin, and his big-screen credits alongside The Italian Job (1969) included Kelly’s Heroes (1970), the strange, troubled and troubling political thriller The Jerusalem File (1972) and Sweeney 2 (1978).

His stock was high after the success of 1983’s eminently watchable, pacey and well-received Reilly, Ace of Spies, which had provided international recognition for New Zealander Sam Neill in a fine performance as the eponymous Sidney Reilly, a swashbuckling Russian-born British intelligence agent in the early decades of the 20th century. The series of 12 episodes, made by Euston Films for Thames Television, had also seen Martin Campbell share directing duties with Jim Goddard, an experienced television director who had worked on The Avengers, The Sweeney and Boys from the Blackstuff.

The cast assembled for Edge of Darkness was not star-studded, many of the actors having enjoyed relatively limited or only supporting exposure until then, but it was first-rate. Bob Peck, at that point principally known as a stage actor, was compelling as the bereaved and grief-maddened Ronnie Craven, while the role of his daughter Emma went to Joanne Whalley; she was only 24 but a veteran of child roles who had acted in Coronation Street, Crown Court, Emmerdale Farm, Juliet Bravo and Bergerac as well as Reilly, Ace of Spies. Although by necessity of plot her character dies in the first episode, she created a kind of moral lynchpin for the narrative arc, a spectral companion for Peck on his exhausting and perilous quest for the truth.

As the disillusioned CIA officer Darius Jedburgh who becomes Craven’s accomplice and comrade, the producers cast Joe Don Baker, a Texan in his late 40s who had played hard-bitten tough guy roles in Bonanza, Gunsmoke, Lancer, The High Chaparral and other American TV staples, as well as starring in the crime drama Eischied (broadcast in the UK as Chief of Detectives). Baker had enjoyed a degree of cinema success too but was not a household name or face in Britain, but his combination of physicality, fatalism and black humour was a perfect fit for the role.

The implacable, imperturbable face of the deep state, courteous but chilling, was provided by Charles Kay as Pendleton, a bland official “attached to the Prime Minister’s office”, and relative newcomer Ian McNeice as his junior colleague Harcourt. Kay (who died earlier this year aged 94) was already in his 50s and an established character actor with roles in the 1974 BBC drama Fall of Eagles, playing Tsar Nicholas II, as Senator Gaius Asinius Gallus in I, Claudius (1976) and Amadeus (1984) as Count Orsini-Rosenberg. He was also a seasoned stage actor with a strong Shakespearean record. As Pendleton, he showed the British state as some still feared it to be in the 1980s: stiff, formal, discreet and by its own lights dutiful but efficient and, when necessary, without scruple.

Ian McNeice, who came from a theatrical family which inculcated in him a passion for performing, showed a different aspect of the Whitehall archetype as the younger Harcourt (he recalled it here for BBC Four years later). He was a close friend and housemate of Bob Peck’s and forged an instant and warm relationship with Charles Kay, partly founded on their shared grounding in theatre. Less forbidding and severe than Kay’s Pendleton, the younger man swooped from supercilious and slightly smug to dejectedly irritated, and carried himself with a certain untidiness. At his core, however, just as at Pendleton’s, it was always clear that these were unswervingly ruthless servants of the régime for whom the end justified any means.

Propping up the leads was a succession of hard-working actors who were familiar fixtures in supporting casts: John Woodvine, Hugh Fraser, Jack Watson, Allan Cuthbertson and a young Tim McInnerny as Emma Craven’s boyfriend Terry Shields. The series also saw appearances as their real selves by broadcasters Sue Cook and Kenneth Kendall, meteorologist Bill Giles and left-wing Labour MP Michael Meacher.

All of these elements came together with outstanding cinematography by Andrew Dunn and a tense, nerve-jangling score by Eric Clapton and Michael Kamen, and produced a gripping drama which was unpredictable, far from implausible and somehow claustrophobic and stifling in its tension. That all the elements were working at such a high level was demonstrated by Edge of Darkness winning in six categories at 1986’s BAFTA Awards: Best Drama Series or Serial, Best Actor (Peck), Best Original Television Music, Best Film Cameraman (Dunn), Best Film Editor (Ardan Fisher and Dan Rae) and Best Film Sound (Dickie Bird, Rob James, Christopher Swanton and Tony Quinn). In addition, Baker was nominated for Best Actor, Whalley for Best Actress and there were also nominations for Best Makeup, Graphics and Design.

That clutch of BAFTAs was no small achievement. Bob Peck saw off not only co-star Joe Don Baker but Ben Kingsley (for Silas Marner) and Sir Alec Guinness (Monsignor Quixote) to win Best Actor, while Whalley was nominated alongsidem eventual winner Claire Bloom (Shadowlands), Frances De La Tour (Duet for One) and Mary Steenburgen (Tender Is The Night). Edge of Darkness won out for Best Drama over Bleak House, taut kidnap thriller The Price and the ever-reliable Minder. There was no suggestion it had been a lean year.

Kennedy Martin’s brilliance was to create a drama which felt freshly and precisely contemporary, suffused by the zeitgeist, yet had enduring appeal. The environmental movement was by the mid-1980s becoming mainstream: the same year as Edge of Darkness was broadcast, the previously fringe and unsuccessful Ecology Party, itself springing from PEOPLE, established in 1972, rebranded itself as the Green Party and began modestly to capitalise on a growing awareness of and concern about environmental issues.

In 1983, the United Nations had set up the independent World Commission on Environment and Development, chaired by former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland. It arrived against a backdrop of environmental disasters: 80 million gallons of oil had spilled into the Persian Gulf in March 1983 after accidents in the Nowruz oil field; the loss of the oil tanker MV Castillo de Belver near Cape Town that August also a major spillage; 500-600 were killed and thousands injured in a series of fire and explosions at the San Juaniuco liquefied petroleum gas storage facility in Mexico in November 1984; the following month, a methyl isocyanate leak at the Union Carbide pesticide plant at Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh killed 22,000.

A colder war

It was not just accidents which threatened annihilation. The Women’s Peace Camp at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire had been set up in 1981 to protest against the storage of nearly 100 nuclear warheads and BGM-109G Gryphon ground-launched cruise missiles by the United States Air Force and attracted tens of thousands of supporters throughout the 1980s. This was mirrored by other protests across Europe, and coincided with an alarming period of instability in the leadership of the Soviet Union.

Communist Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev died in November 1982 after a long period of ill health and decline, and he was succeeded by the ageing former head of the KGB Yuri Andropov, who himself died within 18 months. The Politburo then installed the terminally ill Konstantin Chernenko, already 72 and paying the price for a lifetime of heavy smoking. This rapid turnover of weak leaders alarmed Western analysts at a time when arms control talks had stalled and East-West relations had grown more tense after the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 is often regarded as the zenith of fears of a nuclear armageddon but the shadow of the mushroom cloud was still very much present in the mid-1980s. In September 1984, the BBC had broadcast the Barry Hines-penned apocalyptic drama Threads, which portrayed in horrifically plausible detail the effects of a nuclear strike against Sheffield as part of a general global conflict; it came 10 months after 100 million Americans had watched The Day After on ABC, which examined the same kind of scenario through the experience of the residents of Lawrence, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri. By the time Edge of Darkness was broadcast, a nuclear confrontation was no longer an abstract geopolitical eventuality for ordinary people. They had been confronted with its potential reality in their towns and cities.

(For my money, neither is as terrifying or profoundly disordering as The War Game, a pseudo-documentary about the aftermath of a nuclear attack on Britain, made by the BBC in 1965, written, directed and produced by Peter Watkins. The BBC subsequently decided, with the strong agreement of the government, that it was too disturbing to be screened on national television; it had a limited theatrical release at the National Film Theatre and at international festivals, but would not be screened on television until 31 July 1985, as part of a series of programmes in the run-up to the 40th anniversary of the use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Threads was repeated the following day as part of the same collection.)

This is what Troy Kennedy Martin saw. Distrust of a Consevative government under Margaret Thatcher which, by 1985, was beginning to struggle in the opinion polls against Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party and the SDP-Liberal Alliance which, despite its deeply disappointing results in the 1983 general election, was still regularly polling around 30 per cent support. A Cold War which, so far from seeming a handful of years from thawing, as it turned out seemed perfectly capable of turning white-hot if a crisis got out of hand.

There was also a sense that the more shadowy elements of the state were hand-in-hand with the corporate world and regarded themselves as untouchable in pursuing their own narrow interests: the CIA was actively supporting régime change in Nicaragua, the US had invaded Grenada in 1983 on dubious legal grounds to oust a Marxist-Leninist government and was generously funding the Mujihadeen resistance to Soviet occupation forces in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, though it had made vehement protests in private against the invasion of Grenada, a Commonwealth realm, the British government was publicly as closely aligned with Washington as it had ever been. The ideological and personal rapport between President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was clear for all to see.

The growth of environmental movement provided the final contextual ingredient. Young, idealistic and sometimes naïve men and women, warning that an exchange of nuclear weapons was not the only way in which humanity might destroy itself, were the perfect dramatic counterpoint. The drama could call on recollections of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo in 1961 (in whose death Britain might have been as intimately involved as the US), former Bolivian president Juan José Torres in 1976 and long-standing rumours of collusion between British security forces in Northern Ireland and Loyalist paramilitaries: the idea that the state might resort to murder did not stretch the bounds of credibility.

None of this would have been as effective without an outstanding ensemble cast and first-rate writing and cinematography. Edge of Darkness emerged as the rare kind of drama in which everything fits together seamlessly, and the whole is more than the sum of its parts. If there is one outstanding element, it must be Bob Peck’s mesmerising performance as Ronnie Craven.

The dour Yorkshireman gives a superbly measured portrayal of a grieving widower beginning to piece a life back together when the murder of his daughter opens the door to new levels of existential despair; you can see a man who knows he is not always acting rationally or wisely, who knows the end of the journey may be dark and still has the ability to perceive alternative routes but can no longer will himself to take them and to change course.

Tragedy need not always be unexpected: Craven’s is the oncoming train, inexorable, agonising. In Peck’s deeply etched mask of grief there is something of Homer’s portrayal of the Trojan hero Hector, parting from his wife Andromache. She has begged him not to return to the fighting, afraid of what might befall him. He knows, of course, he has always known.

There is no man who has escaped his fate, neither a cowardly man, nor even a good one, from the first moment when he has been born.

Now Peck’s brilliance carries the sad aura of a similarly shortened life: he was rightly lauded for Edge of Darkness and achieved a greater measure of the fame he deserved. As gamekeeper Robert Muldoon, he raised the tone of the enjoyable hokum of Jurassic Park (1993), and had continued a superb television and stage career, playing Major Mike Norman, commanding officer of the Royal Marines landing party in Stanley, in the BBC’s Falklands drama An Ungentlemanly Act (1992), and Shylock in Channel 4’s 1996 production of The Merchant of Venice.

Fate was already in train, however. Peck had been diagnosed with cancer in 1994 and underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, his agent reassuring people he was beginning a recovery. But he died at his home in Kingston-on-Thames on 4 April 1999, aged only 53. Ian McNeice read a eulogy at the funeral service.

It is easy to be nostalgic and think “They don’t make television like that any more”. The truth is they never did, or hardly did: one of the reasons Edge of Darkness stands out now is that it stood out then, noticeably brilliant on its first showing and attracting four million viewers to the unfamiliar territory of BBC2. Michael Grade, then Controller of BBC1, sensed its potential and it was repeated less than a fortnight later in three double episodes on BBC1 on three consecutive nights, from 19 to 21 December. Grade’s instinct was sound: the audience doubled to eight million.

Four decades on, Edge of Darkness remains compelling and timeless. It is untarnished by the dismal 2010 Hollywood adaptation starring Mel Gibson, an actor as limited as Peck was extravagantly talented, and the equally monotone Ray Winstone as Darius Jedburgh. The public delivered a crushing verdict: the film made $81.1 million at the box office, and had cost the producers $80 million: a hard and elaborate way to make a million dollars.

If you have seen the series, mark the anniversary by rewatching it. If you haven’t, a televisual gem, polished to a hard, high sheen awaits you.

Edge of Darkness is currently available to watch free on the BBC iPlayer.

Image top : Bob Peck in Edge of Darkness