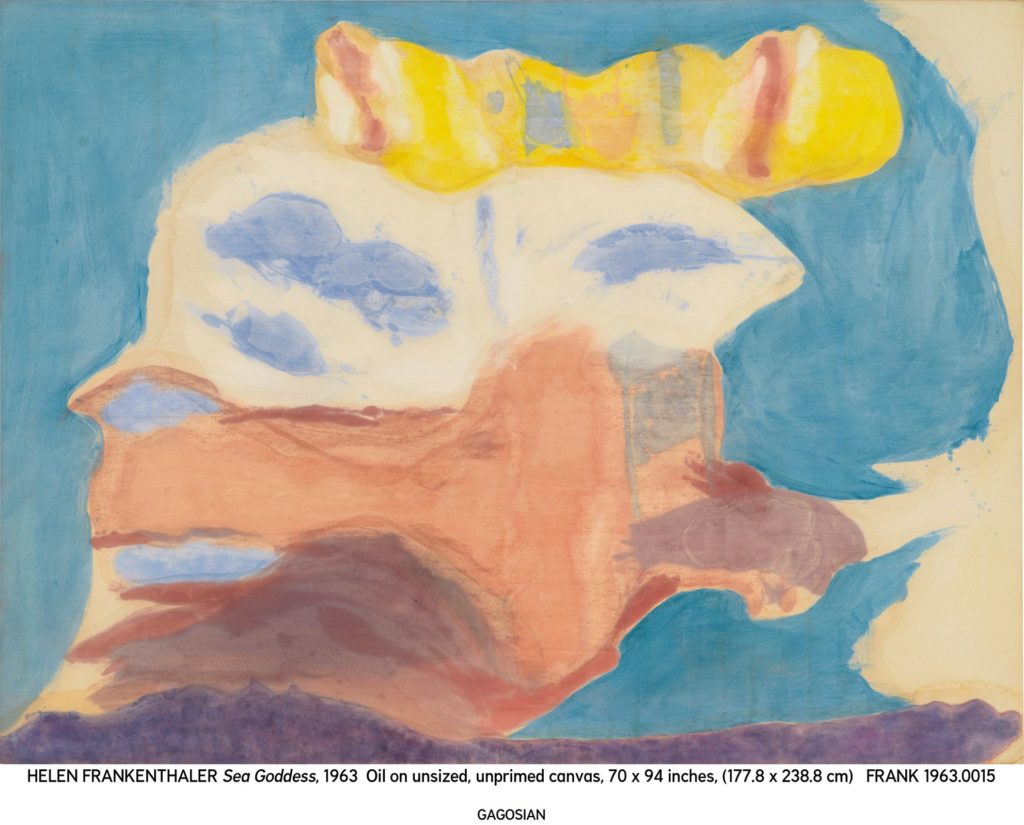

Looking closely at the works of Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) can be an gratifyingly emotional experience. These are big works: the canvases are imposingly ginormous. They present an immersion of colour—the longer you look, the more you’ll be swept in; the more you’ll sink languorously into multi-hued pools. Truly, they are statement pieces: unapologetic, bold and resolutely feminine. As Linda Nochlin wrote in Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (1988), “if daintiness, delicacy, and preciousness are to be counted as earmarks of a feminine style, there is nothing fragile about Rosa Bonheur’s Horse Fair, nor dainty and introverted about Helen Frankenthaler’s giant canvases”.

An exhibition of fourteen paintings from the collection of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, several of which have never been exhibited before, is running at Gagosian (20 Grosvenor Hill, London) until 27 August 2021. This is great, because the colours of the Color Field really need to be viewed in person for their full impact, as to see smaller reproductions in books or, worse still, on screens, is to lose out on the majesty of Frankenthaler’s visual statements. For people who’ve been cooped up in lockdown, unable to leave their homes, unable to travel to see family, unable to conceive of voyaging to new places—or else, locked in a routine of commuting to jobs they hate, unable to think of new pastures—these landscape paintings feel unusually freeing.

This sense of being freed is important. You get the sense that for Frankenthaler, the daughter of Alfred Frankenthaler, a respected New York State Supreme Court judge and Martha (Lowenstein), who had emigrated with her family from Germany to the United States, the act of painting gave her freedoms she otherwise lacked. Painting allowed Frankenthaler to express herself in a world where her privileges—a wealthy upbringing and the cultural, intellectual and social progressiveness of her family—made contemporaneous writings focus on who Frankenthaler was, rather than what she did. There’s a sense of coldness in contemporaneous press: take, for example, Time of 28 March 1969, in which Frankenthaler is “Heiress to a New Tradition”. Words carefully calculated, it would seem, to alienate readers from the artist (then only 41 but with two retrospectives to her name).

However, Frankenthaler was, by all accounts, a characterful, considered and wholehearted person, aware of her own strengths and limitations. Of her childhood, she said in a 1968 interview conducted by Barbara Rose:

I mean my parents since I was a third daughter and I was probably loaded with both real love and real joy thought I was the most wonderful, gifted, complicated, hopeful creature in the world. I mean my father would walk behind me with my mother and say to her sometimes audibly to me, but she would tell me about this years later: “Watch that child. She is fantastic.” And I think in a way I was fantastic. But if somebody, if you have something in you and you have parents who project it, then you’re armed in many ways, that you have some special quality, and they also think you’re a super child, it follows, it also does terrible things.

Oral history interview with Helen Frankenthaler, 1968. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

This super child with self-esteem buoyed by the confidence instilled by her parents must have had a great deal of resilience for the barrage of criticisms she’d face throughout her decades-spanning career, such as the New Yorker referring to her works as “boardroom paintings” and her personality as possessing “high-priestess airs”. Frankenthaler liked to socialise—her renown for being a party hostess was “legendary”, writes Anna C. Chave in Frankenthaler’s Fortunes: On Class Privilege and the Artist’s Reception, and her New York Times obituary, no less, relayed an account by the British sculptor Anthony Caro of being welcomed to New York in 1959 for a dinner party for “some 100 guests,” at which he got “seated between David Smith and the actress Hedy Lamarr”—but to focus on this is to neglect Frankenthaler’s worth as an artist.

I looked at the fourteen paintings of the exhibition thinking of what I’d ask Frankenthaler, had I had the chance. Does colour influence the soul? Wassily Kandinsky believed so, but also believed that through calculated use of colour there were ways of provoking certain responses in people:

Yellow is the typical earthly colour. It can never have profound meaning. An intermixture of blue makes it a sickly colour… Vermillion is a red with a feeling of sharpness, like glowing steel which can be cooled by water… Orange is like a man, convinced of his powers… Violet is… rather sad and ailing.

Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912), Wassily Kandinsky (1866 – 1944)

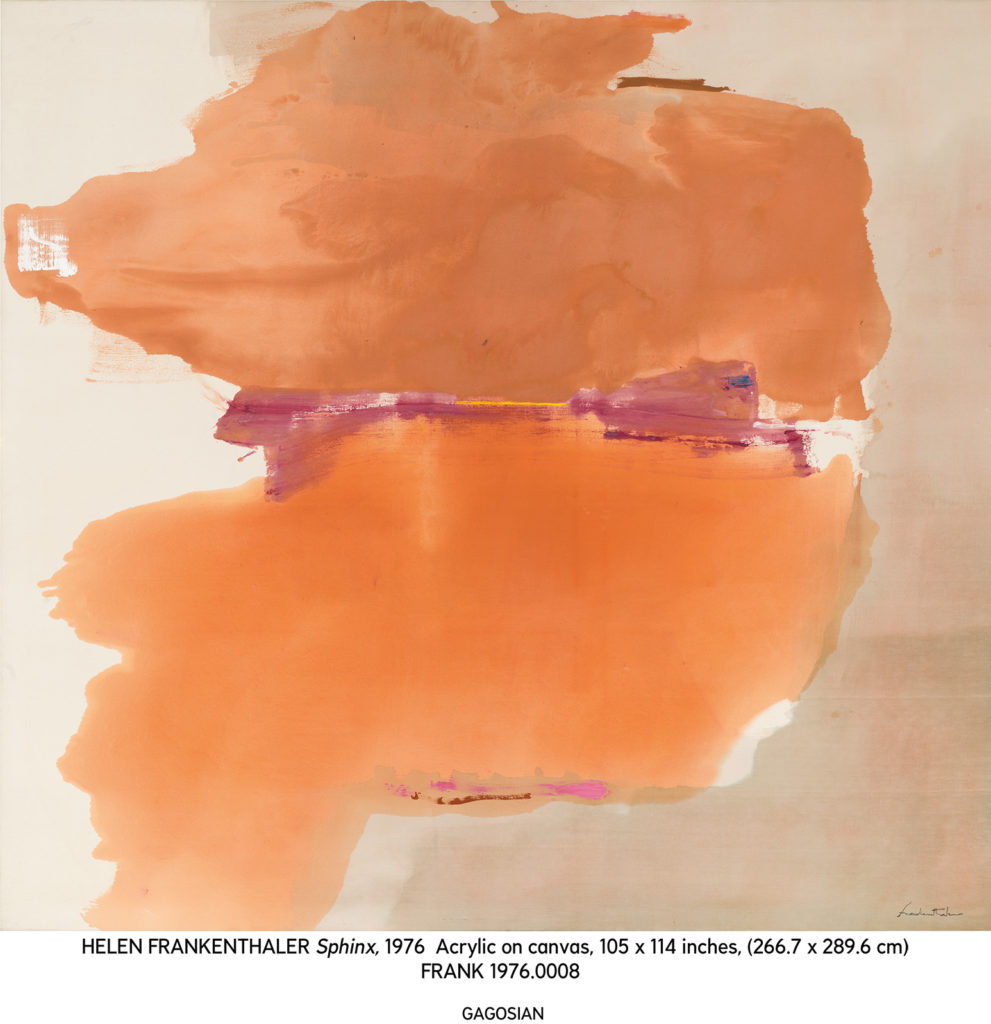

I wonder what Frankenthaler would say in response to this. Her Sphinx (acrylic on canvas, 1976) contains a great deal of orange; was she, in painting it, thinking of a man ‘convinced of his powers’? Or perhaps thinking of Sphinx at Giza, hazy in the sun? I’d love to have asked her. She certainly had strong views about how colour should be placed:

Color doesn’t work unless it works in space […] Color alone is just decoration—you might as well be making a shower curtain.

Helen Frankenthaler as cited by Deborah Solomon: “Artful Survivor” [profile of Helen Frankenthaler] in New York Times Magazine (May 14,, 1989)

Do you think of yourself as a feminist? John Gruen in his 1972 book The Party’s Over Now reports that Frankenthaler once said that for her, “being a ‘lady painter’ was never an issue”, that she didn’t “resent” being a female painter. “I don’t exploit it. I paint.” Maybe that’s not the question to ask. Again, it would asking Frankenthaler to define herself by external terms and boxes, when her focus was on creating meaning through the act of painting.

A line, color, shapes, spaces, all do one thing for and within themselves, and yet do something else, in relation to everything that is going on within the four sides [of the canvas]. A line is a line, but [also] is a color. . . . It does this here, but that there. The canvas surface is flat and yet the space extends for miles. What a lie, what trickery—how beautiful is the very idea of painting.

Helen Frankenthaler

Those wishing to see more of Frankenthaler’s work should note in their diaries that there’s a room of her paintings at the Tate Modern until November 2021, and Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty, the first major UK exhibition of Frankenthaler’s woodcut prints, will open at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, on September 15, 2021.

IMAGINING LANDSCAPES: Paintings by Helen Frankenthaler, 1952–1976 runs from June 17–August 27, 2021 at Gagosian Grosvenor Hill, London. IMAGE TOP: Frankenthaler in her studio on East 83rd Street, New York, 1974. Photo: Alexander Liberman, © J. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles