In December 2021, I was lucky enough to see Ralph Fiennes’ live recitation of TS Eliot’s Four Quartets at the Harold Pinter Theatre in the West End of London: the opening lines, uttered with an arresting solemnity by Fiennes, are:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

TS Eliot

The words are as startling and as unsettling now, in the 2020s, as they must have been when the Quartets were first composed between 1932 and 1943: while at the time, the Second World War hadn’t ended, we now live in no less troubled times, in a world that has seen the atomic Bomb; Man’s inhumanity to Man; the advent of computer technology and the internet; the march of progressive politics only set back by the emergence of populist regimes; the death toll of Covid and its effect upon world economies, and a billion individual tragedies unfolding day by day. Time unredeemable unfurls regardless.

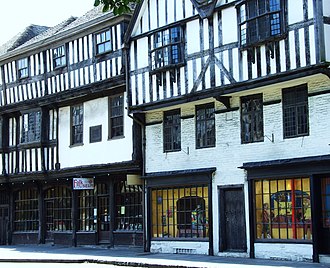

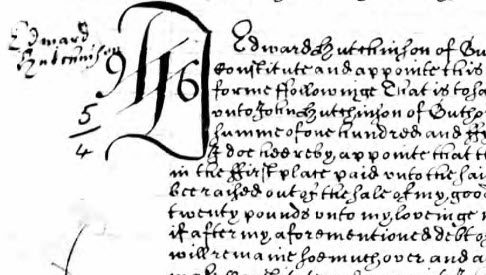

A decade ago I took a module in the history of the English Reformation, taught by Professor Ronald Hutton: when it came to the essay, I chose to focus on analysing Tudor wills. I travelled to Gloucester Archives (recently rebranded as “Gloucester Heritage Hub”) in order to consult sixteenth-century churchwardens’ accounts. I read contemporaneous wills of gentry, all written in ornate and flowery cursive by law writers or else parish clerks, at a small desk, searching for clues. The gentry of the time were the only social class to leave wills: anyone of the lower social orders would either have nothing of value to leave to others in the event of their deaths, or else the price of the legal fees for drawing up such a will would outweigh the value of the objects mentioned therein.

The wills would start with the standard wording and legalese – a testament that the testator was “in sounde minde” and therefore having capacity to think through their worldly goods and the beneficiaries into whose hands the possessions would be endowed. There would follow a usually scant list of items – one thinks of Shakespeare leaving his wife Anne Hathaway only his “second-best bed” – furniture, bed linen, a few kitchen essentials would be typical, providing a stark contrast to all the clutter that twenty-first century westerners accumulate during their lifetimes. The mention of the items was really, it emerged, a serviceable preamble to the matter of true importance within the will: the commendation of the soul.

I drew various wills together to seek an answer to the question of whether Tudor wills truly represented the religious views of the testator, whether they be Protestant or Catholic, or whether the wording merely followed convention and did not make a window into the will-maker’s heart. I looked at, for example, the will of a widow drawn up in 1546, who left her soul “to almighty God, trustinge to be saved only by the Deathe and passione of our savioure Jesus christ”, which seemed altogether Protestant rather than Catholic, in that it did not mention the saints and the holy company, in contrast with the will of 1549 of another widow, whose soul she commended “to almighty God and to the company and fellowship of all the blessed saints and angels in heaven”, a Catholic will. I compared the wordings; I found mostly that the testators’ true feelings were shrouded by the mists of time and therefore largely inscrutable.

I enjoyed the journey to Gloucester Archives. My mother was good enough to accompany me, sitting with me in the cafe beforehand and marshalling the help of a local amateur historian, who kindly offered advice on how to interpret churchwardens’ accounts. An octogenarian, his gait was slow and his hearing sometimes failed him. I spotted him often on the bus going about his business and sometimes in the Archives; he was always alone and I wish now that I’d made more of an effort to be friendly; to break the bonds of British reticence.

One day when my research was done I left Gloucester Archives and headed home: my essay received a distinction. I have not since had any reason to return there, following graduation and a geographical move and change of profession. My time at the Archives is now, of course, time past, just as the lives of the will testators of Tudor Gloucestershire are now time past… and yet, in both cases, remembrance makes them time present. Perhaps the solemnity of Eliot’s words are lost on me in my facile interpretation of them, but opening up the Tudor wills and trying to imagine the lives and psychologies of the will-makers made me, their future, briefly alive in their time past. I’m sad sometimes when I think that my simple, bright spring days of masters degree research are forever over, but perhaps I can take solace in TS Eliot:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

TS Eliot

Image top: Hans Holbein’s The Ambassador’s (1533), a well known allegory to life, death and time. Wikicommons