Ahead of the new series of Lost Relic Hunters, Janina Ramirez explains how we should re-evaluate the Middle Ages and what their female artists and anchoresses can teach us today.

Which mediaeval artist should be as well known as the Renaissance giants but isn’t?

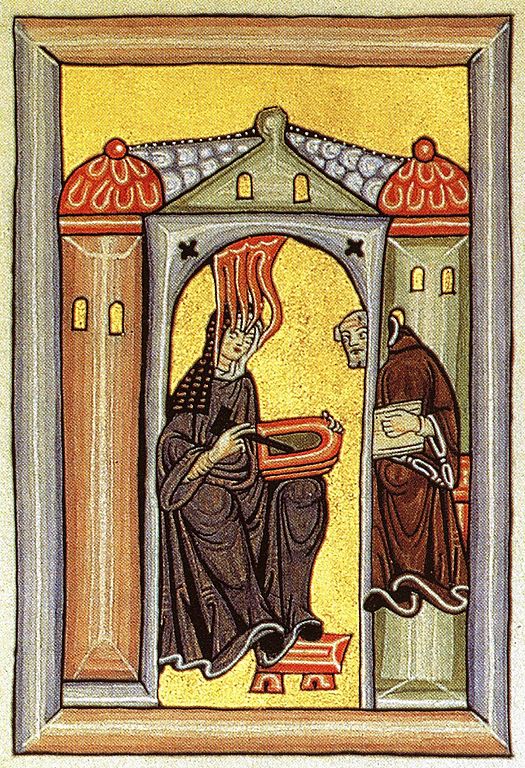

I am on a bit of a mission to have women written back into historical documents, so for me it is Hildegard of Bingen, tentatively of the 11th century. She is extraordinary at everything. I mean she is Leonardo da Vinci born four hundred years before Leonardo da Vinci. She is the most extraordinary woman. She is known as the first natural historian: she was a scientist, she does astrology, she creates a language from scratch, she is a linguist. She’s also a musician: her music still survives and it’s unusually original in that it is polyphonic, it’s so beautiful, she is all these things. She is a writer – a multi best selling international superstar writer, who goes on book tours around the whole of Christendom and commands audiences who just sit and listen transfixed to her latest work.

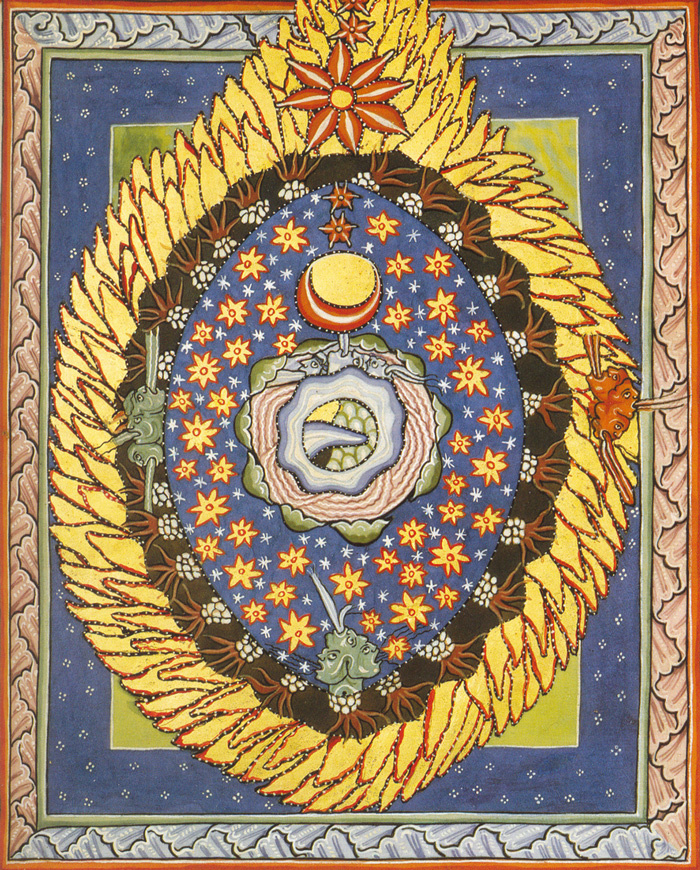

In all of this she is an artist and she illustrates her own works. They are some of the most mind bending images; my new book, Femina has one of her illustrations on the front. These images come from her visions. As a visionary, she had visions from the age of 6, and today we might describe them as migraines or headaches but in these visions she sees psychedelic images of the universe and the one I picked for the one in the front of the book, it sort of looks like a celestial explosion with stars all around, but it is very clear, once you look closely, that it is a vulva and she actually provides the first and only medieval account of female orgasms so she was hugely interested in being quite feminist, quite radical, quite powerful. Her art is, I think, some of the most beautiful medieval art that survives. So Hildegard, not just for her art but for everything that she was and everything that she did.

How was she received by the patriarchy?

Honestly she faired incredibly well. She got her own abbey in Bingen; she created this absolute community of intellectually superior women that nobody could really rival. And she just had so many of the religious men around her who worshiped her, wrote her stuff down and couldn’t get enough of her. She is one of those unusual stories you don’t hear about. She had a good time, she got about as powerful as a woman could get in the medieval period.

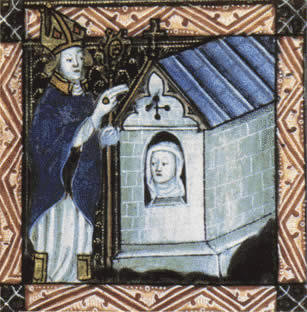

What would the female hermit, Julian of Norwich’s life advice be for people living in 2021?

I think you could say the same thing. When I wrote the book on Julian [Julian of Norwich a Very Brief History], I was rereading Revelations, it was just at the point that Trump had been elected and Boris Johnson and all these changes were happening. There was a real sense of gear shift in the world and I was reading her and I couldn’t believe how relevant it felt. It felt so useful.

The phrase she is known for is “All shall be well, all shall be well and all manner of things shall be well.” which sounds like a cliché but with her it is not. It is so carefully thought out, and those words are genuinely consoling because they are quiet, they are meditative, they are almost mantra-like. They are meant to bring genuine solace. Everything she surrounds those words with in the book is all in this striving for love, striving for something better, striving for kindness.

She saw much worse than we have had. She saw the Black Death and subsequent plagues and she probably lost all members of her family to the plague. She saw heresy trials and where her cell was was right next to where heretics were burnt and she would have heard the screams of heretics – essentially who had been accused of committing a thought crime…

She saw war, she saw schism, she saw the church rip apart. All this in her lifetime and yet she writes this book: there is no ego in it, there is no personality in it, it’s just consolation, consolation, consolation. And we need her now. God, do we need someone like her right now! So I think her words are just as relevant and I think she would keep saying the same things now.

Why have we seen a resurgence of interest in Medieval history – are they getting a new ‘afterlife’?

I’d like to think that it is very different. I don’t think it is just the Medieval period, I think historians in general and the way we study history and the way we talk about it has shifted radically. I point to things like Hallie Rubenhold’s book on Jack the Ripper’s victims The Five, David Olusoga’s work on A House Through Time, and the idea that we are not just looking for the great kings, queens, officers, generals. We want to find ourselves in the past. And a lot of that has been the result of the internet: people searching their own genealogies, people are going back to local records that they have never probably been able to access before.

There is a humanising of history that has been taking place. For a long time history wanted to be seen as part of the social sciences: that it was empirical, that it dealt with facts, data, and dates. Now it is more part of humanities. It is about human stories, it is about the sort of thing I do, which is more “culture history” or storytelling, and I think it is a wonderful thing. The Medieval period is right for it because, out of all the periods we study, it’s been so poorly manipulated in the last few centuries.

That’s the reason I’m writing Femina, because I just think we have an entirely wrong inherited view of the Medieval period. And for anyone that is curious wouldn’t you want to right that wrong? There’s got to be intellectuals out there, across the world who could see that there are errors to be corrected and they desperately want to do it. So that’s why there is definitely rising interest in the Medieval period. There is so much to discover with fresh eyes. Everyday I discover something new and it is just a joy.

On the definition of ‘Medieval’, are there ongoing strands that connect pre-Christian and post-Roman Britain to the High Middle Ages?

All the things that make us human, the things that carry through time. I am currently working on a book Goddess: 50 Goddesses, Spirits, Saints and Other Female Figures Who Have Shaped Belief, and what you tend to see is that everyone of them is unique and individual and distinctive in their human qualities. They largely represent the feminine and all the different manifestations of that – as well as real richness in intellectual conceptualism during this time and all the things that really ties us together: love, childhood, belief in something and intellectual curiosity.

People talk about the Renaissance being a sudden explosion of intellectual activities, as if everyone is dumb before that, as if nobody is using their brains at all. Nonsense! You know, intellectual curiosity just works with the tools it has and I am constantly staggered by the leaps of ingenuity that people are making during this time and there are so many misconceptions still today.

I just had a long conversation today with someone about monasticism and our modern notion of a monk. If one of our friends turned around to us today and said ‘I’m becoming a monk,’ you might think they are religiously on the extreme, under the spectrum and perhaps socially awkward – they’re going to shut themselves in a room and have no sex…

That is so far from the concept of a medieval monk that it is beyond belief. It was a really attractive career prospect for any young man who wanted to be fed or be taken care of while they exercised their brain. They were not blind servants. Monasteries are where you would find the dissidence, that’s where you find the thinkers, the scholars, the scientists, the doctors. Again, we just use our modern terminology incorrectly because we inherited it in the imperial age. I think there is so much to be discovered looking at people with fresh eyes and looking at them like they would have seen themselves.

That Victorian, imperial lense you mention, we’ve broken that?

No. It’s staggering. The number of misconceptions I clear up on a daily basis, it depresses me. We’ve inherited so many bad ideas: the idea of skin colour racism, the idea of class systems, the idea of misogyny, they are so recent, they are a couple of hundred years old. It really depresses me because it is so contrived, so clearly engineered as a mode of control and as a mode of expansion and the imperial imposition of ideas. I think bringing the Medieval period back to a real sense will help us actually as a part of a mental rehabilitation. If we have a more accurate view of where we come from it should encourage us in the future to go forward more boldly. I am a woman, I want to know that we’ve not always been a second class citizen, and that we haven’t always been subjugated and told to be quiet. I can show you that we haven’t and I can go on, into the future, knowing that. It’s a moment of great pivotal change and an important time to be looking at history.

Dr Janina Ramirez appears in the latest series of Lost Relic Hunters, airing on Sky History on Mondays at 9pm

Her forthcoming book Femina is available to pre-order here.

Image top shows a contemporised take on Hildegard of Bingen