When it comes to my books, I always say I don’t choose my subjects; they choose me. That was true for Maria Callas (1923-1977), the most famous Greek-American opera singer of all time. There must be a hundred books on Callas, translated into every language, mainly repeating the usual trivia. So many people claim to have been her best friend, her most loyal supporter, but none to date has said anything new.

A few remain behind, clinging to that bond. To tell the truth, I was always sceptical: I have been an admirer of Callas for over a decade and I wondered how the same nonsense was published time and time again, the same old documentaries being aired. Frankly, Callas is big business.

In today’s climate, the retelling of Callas’s story offers no room for clichés or victim-shaming. Beginning with her childhood, I was horrified to learn of her parents’ abuse, and their total disregard for their child simply because she was female. Here was a girl, not only with a tremendous voice, but fighting for survival, against her mother’s attempts to exploit her, and the lecherous men she encountered at the conservatoire.

When a teacher attempted to rape her, her mother said, “A pity he didn’t manage it. We could have made him marry you, and that would have been that.” In those days, she could not report here attacker nor speak out, so she channelled that rage into her operatic roles. Even today, some are horribly gratified by her suffering.

In the past two years, three enormous collections have been bequeathed to American archives. They have never been published before, and I was the first to see and use them. Researching Callas was always going to be tricky: her story intimidates people. Even her estate is formed by the vaguest of connections who, although they threaten it, have no power. (It’s formed by her deceased brother-in-law’s six friends, none of whom Callas ever met, and a trademark case, from the mid-2000s, claimed her brother-in-law had no real authority over Callas.) Although people have been happy to profit from Callas, there has been no attempt to safeguard her.

The greatest discovery, for me, was the truth about her relationships with Battista Meneghini, her husband, and Aristotle Onassis, her partner. I was given access to Meneghini’s papers, which are in a private collection, and it painted a picture of Callas as a devoted and loving wife to her much-older husband. A previously unseen letter to her solicitor revealed Meneghini as emotionally abusive and someone who stole one-third of her fortune.

As for Onassis, the private letters to Callas’s best friend were difficult to read. Today, we use terms such as “date rape” to describe much of what Onassis did to her—more of that in the book. When she confided in friends, they dismissed her claims. “A woman like Callas wouldn’t put up with that!” And so, she remained unsupported, as were many women of that era.

My research into her cultural identity and the social practices of contemporary Greece and Italy reinforced how incredible she was. In her environment, she had no rights and was first her father’s property and then her husband’s. Under Italian law—she lived in Italy from 1947 to 1962—she could not divorce her husband and in fact risked being imprisoned for committing adultery.

So she was earning millions and dominating the operatic stages, yet she remained bound to patriarchal laws. Even Onassis adhered to the customs of Ancient Greece, namely the Solonian Constitution, whereby any woman who offered pre-marital sex placed herself outside of the Oikos (the family, the family’s property, and the family home). He said that was why he could not marry her, if she were free of Meneghini. Her entire life was a paradox.

Another revealing moment for me was discovering the truth behind Callas’s physical transformation: she lost half of her body weight in 1953. Research has shown she undertook dangerous and experimental treatments by a pioneering doctor in Switzerland, which had grave consequences on her health. By the mid-1950s, she had burned out, and sought advice from Doctor Feelgood (the German quack Dr Max Jacobson) who gave her “liquid vitamins”. These turned out to be vitamin B, amphetamine and methamphetamine—the powerful stimulants speed and meth.

Who was helping this woman? Not her husband/manager. Her health reports, to which I was given access, revealed she had a nervous breakdown in early 1958 and risked being institutionalised, not only for her mental health but an eating disorder—in those days, both misunderstood. I hope others will understand she was a woman at odds with herself.

In terms of her health, she wrote of odd symptoms which manifested in the early 1950s, and continued until her death. Obviously, this will be revealed in the book, but it also proves she was a victim of medical negligence. “You women are crazy,” her doctor said. Having suffered from issues that fall under women’s health, her male doctor finally did investigative surgery and inserted polypropylene mesh into her pelvis. The practice is controversial today, and many women are suing their health practitioners, as the mesh has affected their quality of life. Perhaps I am too attached to Callas, but when I watch old footage, I can see her pain.

There were also neurological issues: the reason for the cancelled performances and the unpredictable nature of her voice. To think, with medication, she could have been spared public ridicule and the private fear she was losing her grip on reality. This was proven in letters from 1974-76, in which she listed her symptoms: labyrinth vertigo, temporary blindness, low blood pressure, numbness, and dexterity issues. She named the neurologist who treated her and I managed to track him down in Rome; he died only a few months ago. In her last days, she self-medicated to ease her pain and died suddenly at the age of fifty-three.

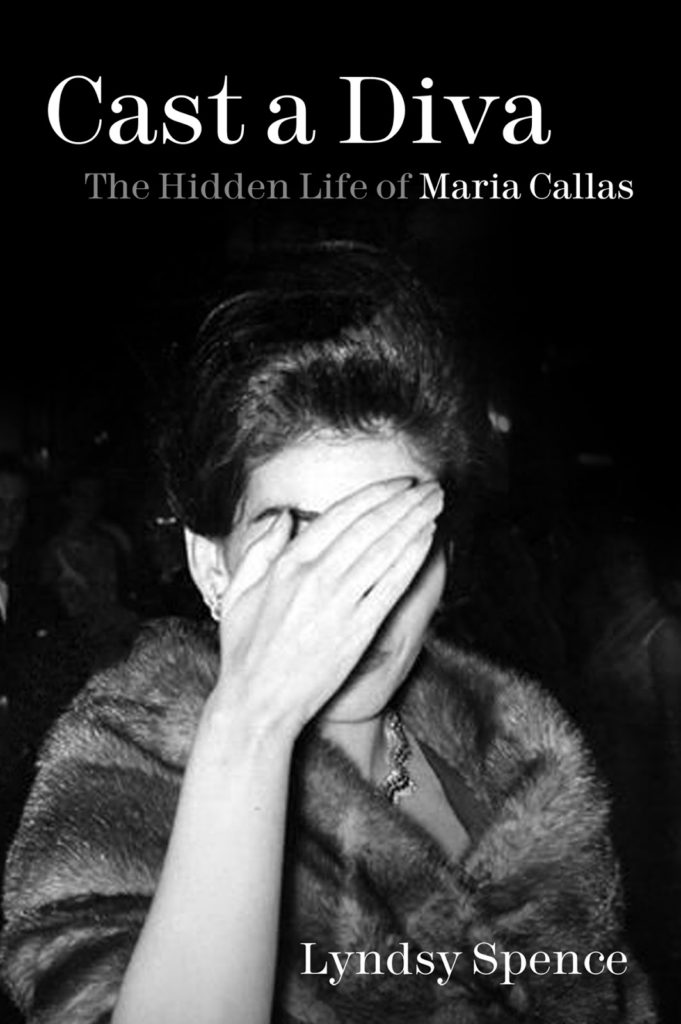

Of course, there is a lot more to Callas’s story and my book is formed from unseen sources. My title, Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas, hints at the contradiction between the artist and the private woman. She said, “I have lived a hidden life,” but that is not to imply it was a shameful life.

“How much of it is hidden?” asked my publisher, before agreeing to the subtitle.

“All of it,” I replied. I hope my book will give a voice to the voice.

Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas by Lyndsy Spence will be published by The History Press in June