‘Resonance’ is the theme of the London Design Biennale being held this year at Somerset House. Unfortunately this phenomenon of increased amplitude does not permeate, masked by too many banal echoes and off-key syncopations. “Can we design a better world?” asks the literature. The most resonating answer appears to be “Not really, the world is in crisis but we’re pretty much fresh out of ideas.”

I was fortunate enough to attend the London Design Biennale in 2016. Charged with design around Utopia, that inaugural exhibition was a riot of ideas and interactions—creating social fusion via border cities, critiquing the refugee crisis and celebrating different cultures in mesmeric colour. The theme, like this year’s, was a deliberately broad one which brought out the best in international artists and designers, and which gave a reassuring complement to London’s status as a global city during a year of awkward social and political reckonings.

That same celebration of international talent is on display here but not with the resonance the exhibition would have hoped to achieve. Bluntly, there is too much recognition of where resonance might be experienced in the issues we all face and not enough creativity in addressing those issues.

That said, there are stand-out exhibits. Finland’s Enni-Kuppa Tuomala has designed an Empathy Echo Chamber in which participants can ask about and explain their feelings. Part-chillout room, part-biohazard decontamination tent, there’s a sense it’s commodifying our sensitivities. That’s not a problem: Tuomala argues it provides a space to recognise and deal with them, and explains how the questions you are asked are themselves designed carefully to encourage emotional resonance between the two participants.

Latvia’s entry also has direct participation. Inspired by the literature of the Baltic State, their newsletter, The Introverted Times, declares “Latvia is one of the world’s most introverted countries in the world and we take pride in that… Literature is the perfect place for introverts.” There is a refreshing and unpretentious mischief here. Visitors can say anything they like into a small speaker. They will then receive an ‘answer’ from the contemporary writer working away behind the scenes.

“If I get a tattoo, what should it say?” I ask.

A small slip of paper is returned in the draw:

“A person has the right to be bad.”

There’s certainly a degree of individual resonance there then…

Not a token gesture

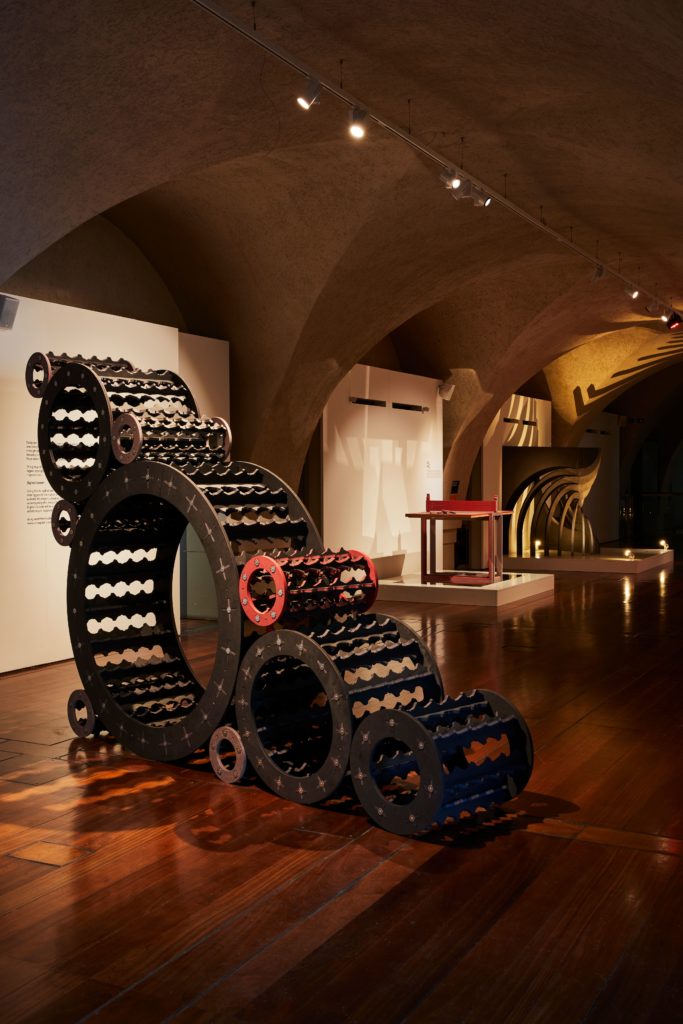

If there is one exhibition which did feel resonant with these changing times, it was the Austrian installation. Tokens for Climate Care allows you to create a uniquely designed token based on the three principles you choose to uphold in the name of climate care. Such projects do already exist left field, but this installation explains and personalises the power of digital design and technology. It engages the individual in changing the world, albeit from a small permanence, and utilises a cutting-edge design approach that is lacking in many of the more staid approaches that mark cultures without disseminating ideas.

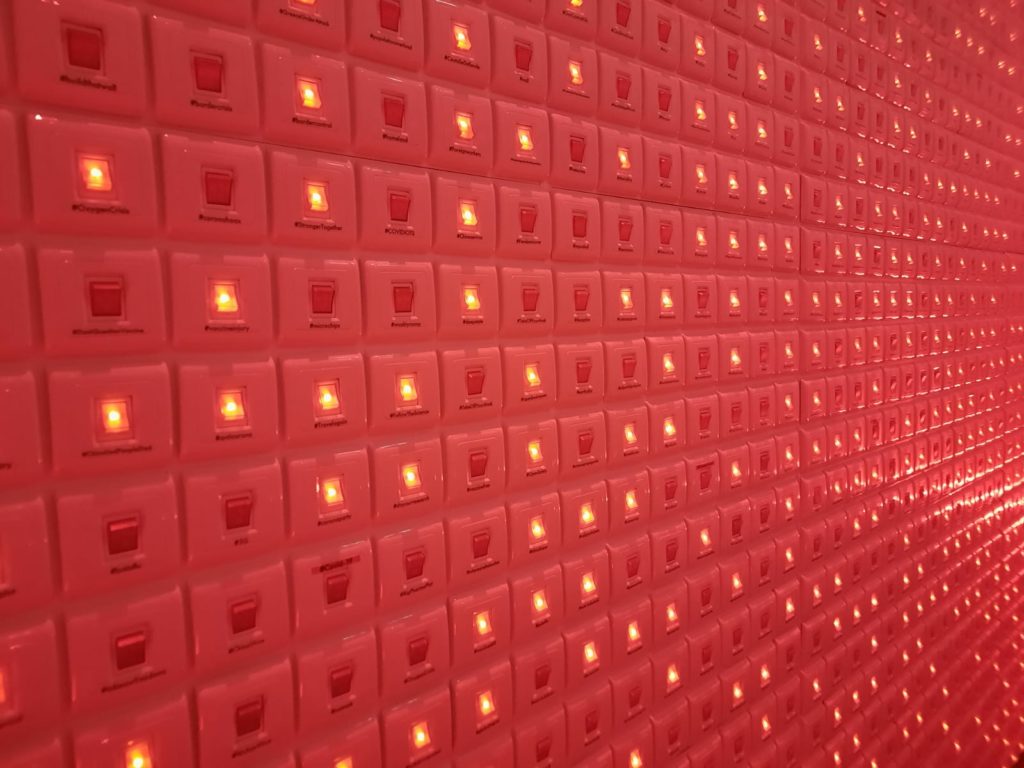

There are other memorable entrants: Israel critiques the on/off trigger points of outrage and anger that social media engenders, while the collective from the Levant and Middle East, Designers in the Middle, finds common ground in reimagining the everyday, from language to table tennis.

But there are too many simplistic ideas expressed through clumsy echoes of the status quo. Canada’s ‘Duc(k)t’ asks us to duck under a duct to think about energy consumption; Antarctica is represented by algorithmic footage of an iceberg to show that it is melting; Greece’s reflection of the image of an olive tree in a mirror is pretty but banal. This is sixth-form commentary, not award-category international design. Designers do themselves no favours in asking their audience to ‘consider’ or reflect on what they have most likely known all their lives. They risk disengagement by such meek efforts, suggesting design does not have the ideas, let alone the answers. The Global Goals forest centre-stage in the courtyard is joyous to experience but struggles to resonate, feeling more like a tired echo of so many urban initiatives, rather than the engine of change that design can be.

It feels unfair to come down on the biennale given the small miracles performed by the organisers and exhibitors to make it happen at all during a global pandemic – like so many major events, it was initially scheduled for 2020. However, this is only its third edition, following two creative and meaningful chapters. Given the gamut of culture UK residents might be expecting this summer, standards are more important that ever. As the biennale’s artistic director, ES Devlin, notes: “We live in an age of hyper resonance, the consequences of which are both exhilarating and devastating. Everything we design and everything we produce resonates.”

In trying to realise what this really means, especially in the context of the crisis we are living in, the exhibits here have made their mission for resonance tautological, not transcendent. Ultimately, the resonance is of a quiet mismatch of endeavour and clarity that exposes, not espouses, too much of the design on display.

The London Design Biennale is at Somerset House until June 27