The Penacho de Moctezuma, an Aztec headdress synonymous with Mexico’s history, continues to hold political and diplomatic resonance today. Since September 2020 Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and his wife Beatriz Gutiérrez Muller, who holds the presidency of the Honorary Council of the Historical and Cultural Coordination of Memory, have challenged heads of state around the world to loan back to Mexico objects integral to Mexican history. The most iconic of these archeological pre-hispanic pieces is the renowned Moctezuma plume.

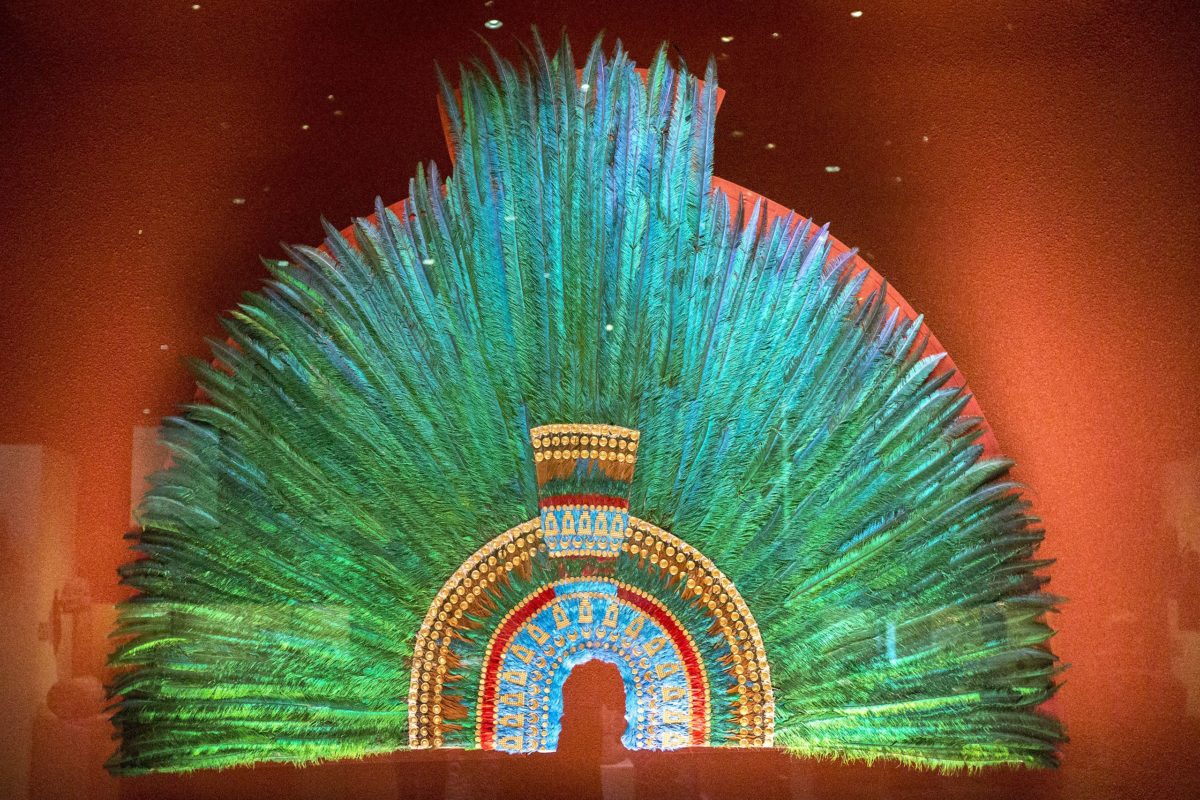

The creation of the headdress and its expatriation has parallels with Mexico’s own difficult origins in the confluence pre-Colombian and colonial narratives. Measuring 1.3m by 1.78m, it combines the feathers of four birds: the green quetzal, the blue cotinga, the pink spatula bird and the red brown squirrel cuckoo, mounted on a base of gold and precious stones in the early 16th century.

Its name originates with the most widespread theory about its origin: that the plume was a gift from Moctezuma to Hernán Cortés when the Spaniard arrived on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico at the beginning of the 16th century. However, there are no indications that the precious object was used by the Tlatoani (Aztec ruler) Moctezuma, as this type of headdress was more commonly used by priests for ceremonial rites.

Mexico has sought the repatriation of the plume for decades, without any success. However, these recent attempts by the current administration to secure its return loan coincide with 2021 — a year marking the most significant milestones in Mexican history: the 200th anniversary of independence, the 500th anniversary of the Spanish conquest and 700 years since the founding of Tenochitlán, the heart of the Mexica Empire.

Earlier this year Gutierrez Muller’s visited the Austrian President Alexander Van der Bellen, to request the loan of the penacho, as in 1991, this was denied. Austria asserts that the plume is not in the condition to withstand a transatlantic trip. Any vibration during flight and any journey on the road could irreparably damage the plume.

No small pawn

European ownership of so much pre-Colombia heritage encapsulates the difficult history of post-colonialism and few would argue the penacho should call Austria its rightful home. That said, if it is recognised as one of the most valuable objects of Mexican art then why risk losing it completely?

There are other politics at play here too. There is little doubt the denial of the loan by Austria was made with full knowledge of a Mexican law that states that if Mexican archaeological objects were to pass through Mexican territory, their repatriation would automatically be generated.

As a Mexican, I cannot agree with the demands of the Mexican president, who demands the headdress back without taking into account the consequences that the trip could have on it. He has even created a rhetoric where Austria is a thief by keeping the penacho under their custody, when the headdress almost certainly made its way back to Europe as a gift.

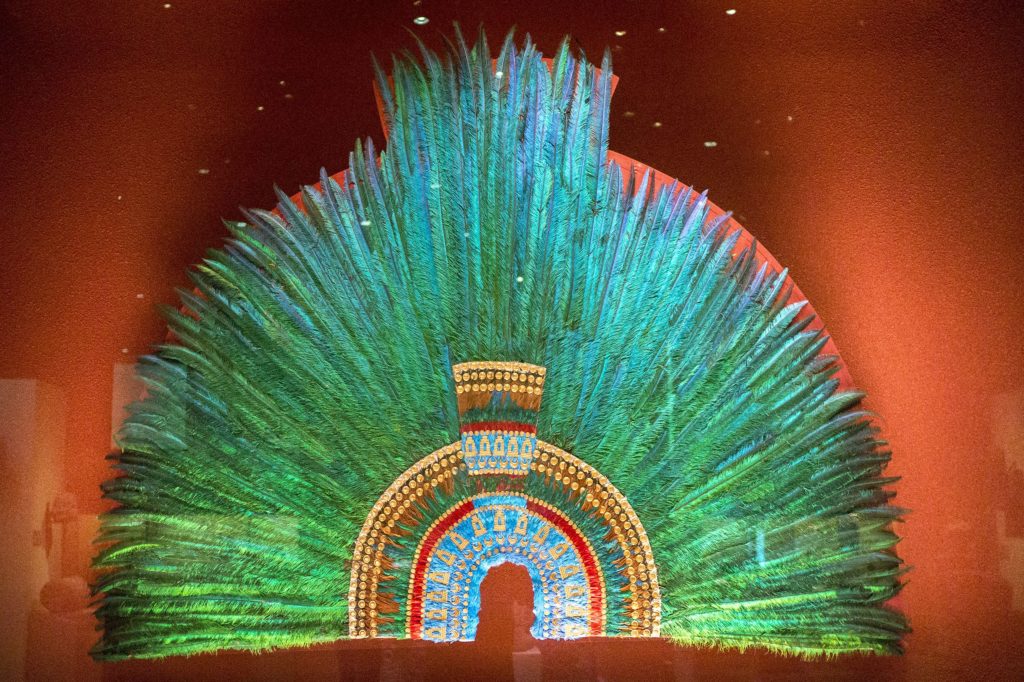

The Penacho at Austria’s Museum of Ethnology c.1955

Having previously worked on numerous international exhibitions of Mexican art, I feel compelled to ask ‘why don’t we think about a bigger and broader vision?’ The recent challenges of covid have proven digital curation and given us time to reflect and celebrate cultures beyond their traditional silos. So why isn’t Mexico speaking about collaboration with states who own key Mexican pieces to create worldwide exhibitions whose central objects are “the jewels” requested by Lopez Obrador? Objects found outside of our country are our most fervent and loyal ambassadors, always talking highly about our culture and our massive wealth of heritage. Why not let them do it one more time in 2021 and let everyone around the globe explore the depth of the pre-hispanic cultures who settled in what is now Mexico.