Why should I bin my beloved self-help books, cast aside my celebrated business manuals and nonchalantly rehome my self-development pocket editions, and instead look at stories from the tragic plays of fifth century Athens for strategy ideas and cultural instruction, an astute-minded business professional may well ask. Why indeed?

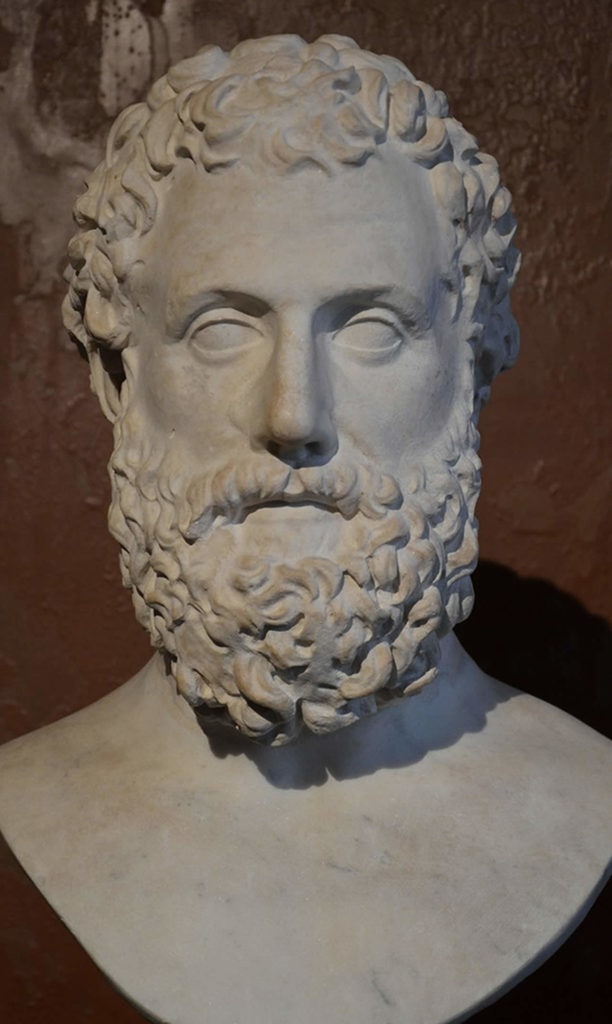

It is widely acknowledged that the three greatest Greek tragedians were Aeschylus (c.525-c.456 BC), Sophocles (c.497-c.405 BC) and Euripides (c.480-c.406 BC). Far from being our cultural contemporaries, the playwrights lived in a society almost completely unlike our own — a society in thrall to myths and legends; a warrior culture; a god-fearing culture — and yet plays from this period are still regularly performed today. Why?

Many classicists, including Daniel Mendelsohn, have argued that the Greeks saw tragedy not just as a form of popular entertainment in which myths were re-enacted, but also “as a form of political dialogue” in which the nature of power was explored and contested. As the nature of power is widely debated in the business books of today, it’s worth having a look at the debate’s historical and cultural precedents.

Try to empathise with your business adversaries: a lesson from The Persians

The Persians, Aeschylus’ oldest surviving play, was first performed in 472 BC. The war with Persia was still in progress, so this really was the cutting-edge drama of the time, relevant to everyday concerns and thoughts. It tells the story of the Persian fleet’s defeat at Salamis and narrates how the ghost of the late Persian King Darius accuses his son, Xerxes, of hubris against the Greeks for having waged war upon them in the first place.

In creating such a play, Aeschylus is asking his Athenian audience to look at the Persian fleet’s defeat at Salamis through Persian eyes: in doing so, he attempts to elicit great sympathy for the Persians, including Xerxes. It’s a lesson that can be used to good effect in business: don’t blindside yourself. Try to see any problems from your competitors’ or detractors’ viewpoint, in order to gain a more holistic sense of the issue at hand and to move forward in a constructive way. Likewise, those brands that have modelled and understood competitors can understand how to talk to their markets too….

Don’t impose your personality on your organisation, let people be themselves: a lesson from The Bacchae

Euripides wrote 92 plays (maybe more), of which only 17 survive. To Aristotle, the work of Euripides is the most tragic of the three tragedians; his appeal to our sympathy is strong because his characters seem human. Euripides depicts mythical heroes not as insurmountable ideals, but as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, while showing sympathy for all victims of society and circumstance.

The Bacchae can be viewed as a cautionary tale against hubris, or the undesirable trait of overweening pride. King Pentheus of Thebes refuses to acknowledge Dionysus as a god, and therefore refuses to worship him. The women of Thebes (including Pentheus’ mother) have run off to the mountainside, shirking their household duties, in order to become Maenads and to act wildly, in worship of wine god Dionysus. Pentheus, keen to uphold order, tries to imprison Dionysus but is tricked by the god into clandestinely viewing the maenads, dressed as one of them and infiltrating their ranks. They catch sight of the king and tear him limb from limb, his mother Agaue holding his head aloft in the mistaken belief that she holds the head of a lion. When the grim truth dawns on her she is banished: Dionysus is triumphant.

The Bacchae can be seen as a struggle between the forces of control (here represented by King Pentheus) and of freedom (that of the liberated Maenads and of Dionysus). In a modern business sense, let’s say that Pentheus represents the patriarchal business leader, keen to project their own values and sense of self onto an organisation. Dionysus and his maenads, then, represent the wider workforce, each with their own ideals and values of their own. If the views of the business leader and those of the wider workforce are not aligned, chaos may ensue: these things must be kept in balance. We’re not suggesting any CEOs will get pulled apart by raving and rebellious staff but control shouldn’t be at the cost of creativity. In recent years, especially in the tech sector, we’ve seen the winning companies nurture individual agency via ‘intrapreneurship’ where individuals are encouraged to see their ideas through to fruition. These are just two examples, but many more lessons are to be drawn from the rich and fruitful world of Greek tragedy. It’s worth revisiting or discovering anew the revered tragic plays of fifth century Athens: while society differed greatly to our own, facets of the human condition and more precisely, the nature of power, can be used profitably to understand and reinvigorate modern day work culture.