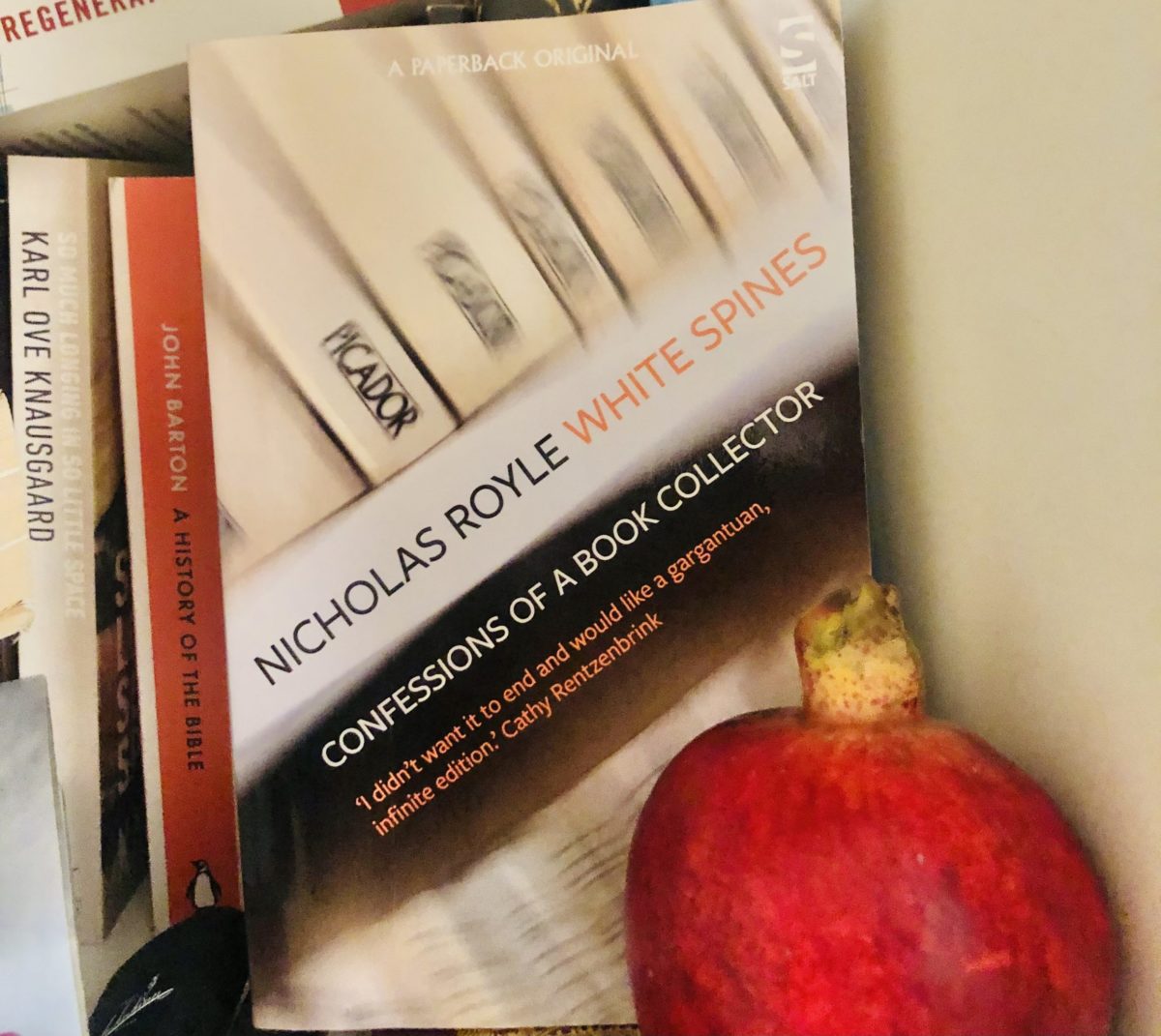

When you describe someone as bookish, you either mean devoted to study or else enamoured of books themselves: Nicholas Royle, writer of White Spines: Confessions of a Book Collector falls predominantly into the latter camp: he is enviably knowledgeable about books; he hunts books down; he collects them for their own sake rather than their monetary value or to exchange with other people. His enthusiasm is both invigorating and infectious.

Lockdown meant that everyone was reduced to scrolling endlessly through Amazon in order to buy books: Royle’s passion for second-hand bookshops will make you want to give up the ease of the e-order in favour of physical, in-person book-buying. Didsbury Village Bookshop is a “narrow, labyrinthine, bare-boarded room” with books “piled up on the floor or spilling out of boxes”; Church Street Bookshop in Stoke Newington, north London, is “a wonderful little one-room shop with clearly laid-out sections”. Bookshop proprietors are by turns friendly, funny and informative; books either elude the grasp of the narrator or are found, to Royle’s annoyance, to be available for purchase but only in an edition that is not desired. But this renders the hunt for the right editions all the more urgent and gratifying, and the thrill of the chase all the more vivid. On page 80, Royle thinks in a moment of introspection that he is “perhaps overly concerned with [books’] appearance, but [he] also respects and can become deeply involved with their contents”. Picador books published between the 1970s and 1990s are coveted and sought after, to be found in many shops dotted up-and-down across the country.

Royle admits to occasionally buying a “non-Picador second-hand book” that he doesn’t really want, but only if it has a “sufficiently interesting inclusion”. These come, sometimes, in the form of personal letters stashed away in the pages of the second-hand books: vignettes into the lives of strangers from which one can draw impressions while knowing nothing of the writers. As Royle writes, they “tantalise with partial information”; they suggest mysteries; they ask the question “who was this person and why did they give away or sell this book?”

Non-writers will wish they were writers on reading White Spines: it’s full of charming anecdotes, such as that of Saturday 11 February 2017, when Royle sets out to find a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which he needs for a story he’s writing about hoopoes. We readers follow him and live his book-finding adventures vicariously, charging along with him down the motorway in a car in search of another Picador tome, or walking gamely across shop floors, smug at the thrift of having saved money on an edition found for several pounds less in a second-hand shop than elsewhere.

At one point Royle goes for coffee in Coffee Circus in Crouch End and overhears a couple in their thirties discussing their mutual friend: whether Royle enjoys his coffee or indeed which coffee he opts for is not mentioned, but the hum and the feel of the afternoon air is captured perfectly by Royle’s pen: throughout the book, snippets of conversations pepper the book-search and are humorous and lively. Book collections are about far more than having a Zoom background that suggests intellectual prowess: Royle makes the case for collecting stories for their own sake; for the connectivity they evoke between us as people.

White Spines: Confessions of a Book Collector by Nicholas Royle is available from Salt Publishing