In her day, the Amsterdam painter Thérèse Schwartze (1851-1918) was a celebrated portraitist who combined talent and expertise with a head for business. She produced likenesses of the Dutch elite and members of the royal family in a notably un-Dutch style, becoming a millionaire in the process. Schwartze also established an international reputation, with countless exhibitions and commissions throughout Europe and the United States. The seemingly effortless brilliance with which she turned out elegant (and sometimes flattering) likenesses of her wealthy clients earned Schwartze much success, but also harsh criticism, especially from advocates for democratization and the renewal of society and art.

Of crucial importance were the upbringing and training she received from her father, Johan George Schwartze (1814-1874). Truly a “citizen of the world,” born in Amsterdam to German parents but raised in Philadelphia, he had studied painting with no less a master than Emanuel Leutze before moving to Düsseldorf for further study. Like a modern “tennis father,” Johan began drilling Thérèse from the age of five; at 16, she promised to try even harder, so as “to be able to earn my living by painting.” Their shared objective was highly unusual in an era when middle-class women were expected to marry early and well, relying only on their husband’s income. Thérèse’s artist-friend Wally Moes recalled that, “Because of her father, there was an American element in her character: she did everything on a grand scale and had a certain audacity that Dutch people tend to lack… If painting had not been in her blood, she would have undertaken something else and made a success of it with the same conviction and passion.”

In 1919, the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant made a conservative estimate that Thérèse had produced approximately 1,000 works of art. This is a substantial number, even bearing in mind that her career spanned forty-odd years. Since this translates into an average of more than 20 works per year, we can assume that each commission took Schwartze approximately one or two weeks to complete. Such productivity appears to have been driven in part by her unflagging desire to provide for her extended family, especially since she had no husband. Her determination is revealed by an experience in 1884, when Schwartze and Wally Moes spent four months in Paris painting, exhibiting at the Salon, and networking. On one visit, Thérèse used a moment of inattentiveness on the part of their host to ensure that they would not be late for another important visit. “On impulse,” recalled Moes, “without giving the matter a second thought, Thérèse swiftly crossed the room to the mantelpiece and put the clock an hour forward. Great astonishment on the part of the host, and profuse apologies for being so late.”

Even after she had become a millionaire, Schwartze continued working with undiminished energy. Her reasons may have been determined partly by her family’s history of immigrant entrepreneurship in the Netherlands, Germany, and the U.S. A strong will to succeed − and recognition of the very real possibility of failure or bankruptcy − were among their defining traits. This makes it easier to understand why Schwartze focused primarily on commissioned portraits, the sale and price of which were always fixed in advance.

Dutch Portraiture

The economic and cultural passivity that gripped early 19th-century Holland was reflected in the period’s paintings. According to the historians Jan en Annie Romein “the renewed middle class of the 19th century, with it’s atmosphere of domesticity and its lack of fresh air, did not give rise to any fascinating new aesthetics.” The relatively modest demand for portraits was met by the sedate, skillfully painted images produced by the likes of Cornelis Kruseman (1797-1857) or his second cousin Jan Adam Kruseman (1804-1862), or by Jan Willem Pieneman (1810-1860). These were Schwartze’s precursors.

In the 1860s, however, the Netherlands entered an era of economic recovery, with a rapid expansion of trade and industry, banking, and the transport network. The country started to recover some of its faded international prestige, and the nouveaux riches sought to affirm their new status just as those with “old money” had done back in the 18th century – by commissioning more dynamic portraits. The time was ripe for an artist with Schwartze’s talents: her cosmopolitan background, combined with a flair for pictorial elegance and even ostentation, opened a new chapter in Dutch portraiture.

Schwartze’s early portraits are fairly subdued. Her stylistic development can generally be described as progressing from a meticulous technique using darker colors, borrowed from German role models like Franz von Lenbach and Karl von Piloty, toward a lighter tone and more vigorous brushwork influenced by French and Dutch Impressionism. Until 1885 she worked exclusively in oils, then gravitated toward pastels, with which she began experimenting in 1881, and which further encouraged her lightening of tone. Even Schwartze’s fiercest critics have praised her pastel works for their virtuoso technique. Oddly, we do not know who taught her to use pastels, and it is just possible that she taught herself by studying the works of earlier pastelists. Her first biographer, Willem Martin, points toward several British and French masters from the 18th century, whose portraits Schwartze “must have seen hanging in numerous family homes.” She surely appreciated the fact that pastels are easy to transport and require neither a palette nor a waiting period to dry.

Style to Order

Because she painted for a living, Schwartze had few qualms about bowing to her clients’ preferences. This obliging attitude is well illustrated by the 1916 portrait of the six Boissevain girls, illustrated here. When the parents asked Schwartze to depict their daughters, they were already familiar with her 1906 portrait of Aleida Gijsberta Maria van Ogtrop-Hanlo with her five children.

The latter still makes a lively, modern impression thanks to its light coloring and loose brushstrokes, as well as the almost nonchalant poses and arrangement of its figures. This approach did not suit the Boissevains, however, who asked Schwartze to produce a more classical portrait. The result thus makes a more old-fashioned impression, with its darker colors, precise draftsmanship, and conservative composition. Here Schwartze quotes several renowned precursors: Velasquez in the girl who stands furthest to the left by the curtain, and Raphael in the angelic child resting her arms on the balustrade. Clearly Schwartze knew well the precedents of such forerunners as Titian, Rubens, van Dyck, Rembrandt, and Gainsborough, and could quote them when necessary.

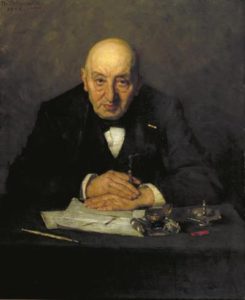

A fine example of a male sitter’s portrait is illustrated here: as director of a textile wholesaling firm, Mozes de Vries van Buuren introduced employee benefits such as health insurance and pension funds, making him a much-loved employer in the age before statutory social security provisions. His company also loomed large in the socio-cultural fabric of Amsterdam’s Jewish community: besides providing employment, it functioned as an informal marriage market. Here, as in so many of Schwartze’s commissioned portraits, the sitter gazes straight at us with confidence, enhancing our respect for him and implicitly reminding us of historical portraits of monarchs and nobles.

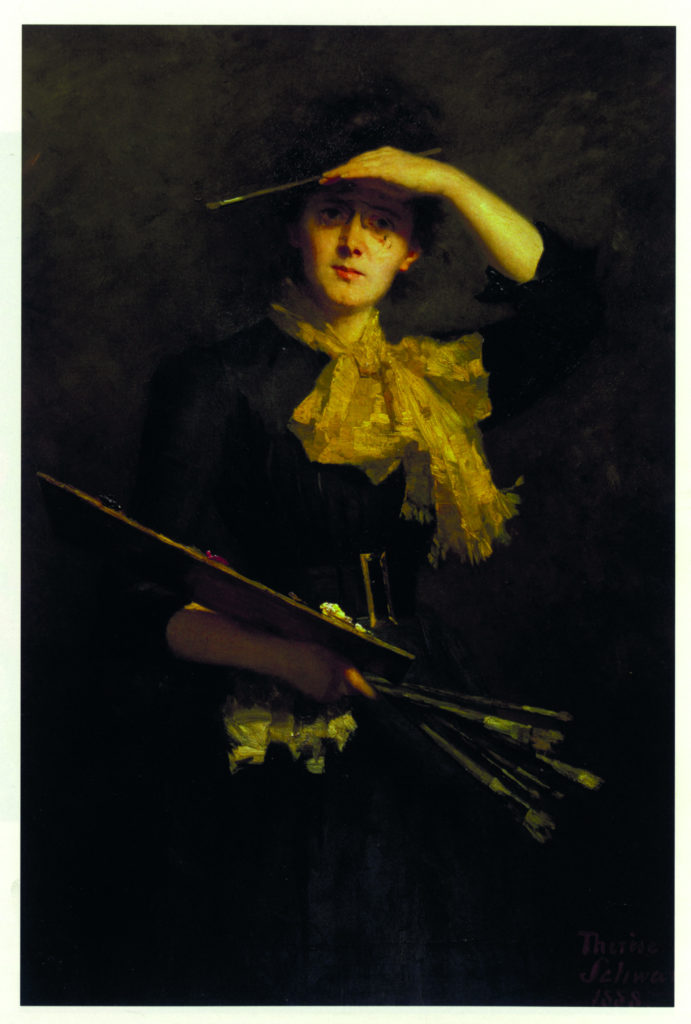

Schwartze’s self-portraits are something completely different. In 1888 she received the signal honor of being commissioned to paint one for Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, which still exhibits its collection of international self-portraits in the Vasari Corridor that crosses the River Arno. It makes sense that this canvas earned Schwartze a silver medal at the 1889 Paris world’s fair, given the meticulous planning of its composition, in which the diagonals of her palette and paintbrushes, along with the shadow created by her upraised hand, create a memorable sense of movement and contrast. Willem Martin observed that Schwartze “had (and this is extremely clear from the portrait) a very uncomplicated nature: she was not someone who was tossed hither and thither by doubts.” Her self-portraits functioned as a kind of advertisement, which was partly why Schwartze included them in various exhibitions. She circulated engraved and lithographed reproductions of the Uffizi picture, and also commissioned photographs of herself for publication in newspapers and magazines.

Schwartze’s portraits of her friends and relatives were not commissioned, and thus reveal much more variety in the sitters’ poses and the taking of artistic liberties that could not be risked with paying clients. These are seldom presented from a frontal perspective, and often the face is half hidden in shadow; they also are more likely to feature loose Impressionistic brushwork. A fine example in this regard is the portrait illustrated here of Schwartze’s niece, Theresia Ansingh, who later became a member of the Amsterdam school of female painters known as the Joffers, many of them inspired by Schwartze’s professional success.

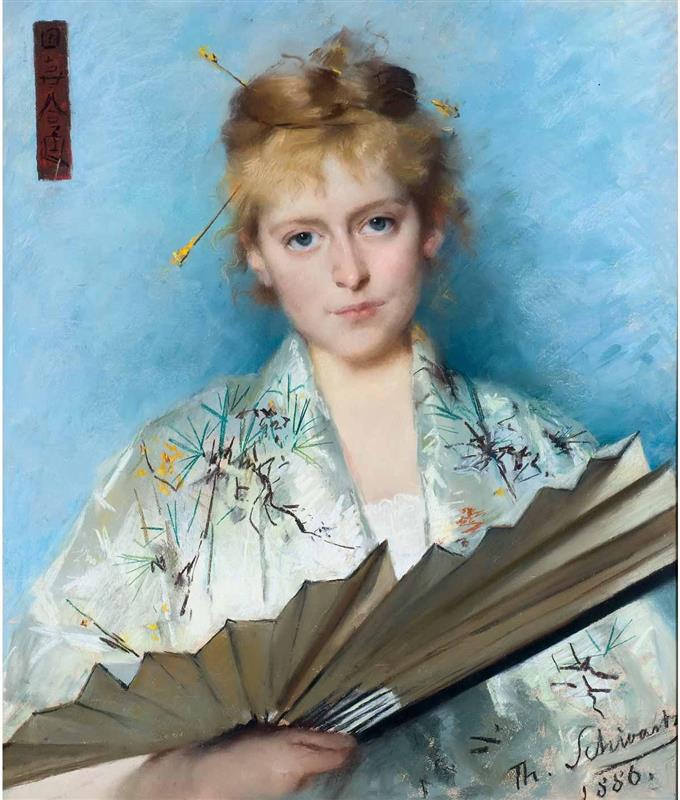

One fascinating portrait that straddles the boundary between formal and informal is that of Mia Cuypers (1864-1944), a daughter of the architect Pierre Cuypers, who designed such famous buildings as the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam’s Central Station. In 1883, she fell in love, to the dismay of her family and the astonishment of “high society,” with the Chinese-British merchant Frederick Taen-Err Toung from Berlin, who was in Amsterdam selling his Oriental merchandise at the International Colonial Exposition. Mia weathered the social commotion and married Toung in 1886. A close acquaintance of the Cuypers family, Schwartze was commissioned by the groom-to-be to make this wedding portrait, which supposedly took her only one and a half days to complete. The Chinese characters in the upper left corner mean “rice field,” “longevity”/”delighted,” and “coming together.”

Although she worked primarily on commission, Schwartze also produced independent pieces for the trade – largely figurative paintings, but also landscapes and still lifes. Many of Schwartze’s figurative pieces feature young girls and women. Those from higher social classes are armed with a book, mirror, guitar, or harp. Those from humbler origins often appear in traditional dress and without such attributes. Among Schwartze’s favorite sitters were girls from the Amsterdam Orphanage, who wore decorative red, white, and black uniforms, and also girls making their first communions and confirmations, where the white veils connote purity. A fine example in this genre is Mother and Her Children in Church, which made its way to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts via the prestigious collection of the Scottish-born, Canadian-based entrepreneur Lord Strathcona.

Time Is Money

Working at high speed was one of Schwartze’s defining traits. In oils, she used the “wet-in-wet” method: the sections she was working on had to be completed while the paint was still wet, within no more than three days. The fresh appearance of her most successful portraits is partly attributable to this intensive method, and indeed many portraits were completed in a matter of days. Schwartze often referred to professionally made photographs of her sitters as aides-memoires, yet she always enhanced his or her dynamism to make the image her own. Though many late 19th-century artists consulted photographs, few admitted doing so because “purists” dismissed them as a crutch.

Willem Martin notes that “The initial sketch would be laid in quickly amid continuous chatter, in which the painter herself would join in, with the somewhat absent-minded attention that followed from the nature of her work, or while [someone] read from an exciting novel or even the newspaper.” Schwartze was eager to ensure her sitter was never bored, so speed and cheerfulness were deployed to help foster an animated likeness. These qualities also seem to have been integral to her character: her contemporaries describe her as witty and entertaining, though to what extent she cultivated this impression is hard to say.

Because working in pastels is faster, Schwartze initially sought less money for portraits done in that medium. But soon after the enormous success of her 1888 pastel depicting the seven-year-old Crown Princess Wilhelmina, she changed her policy. Every self-respecting citizen now wanted his or her children to be regally immortalized in pastels. Naturally, Schwartze responded by raising her prices. Whatever the medium, busts cost less than three-quarter lengths, which were cheaper than full-lengths, and hands cost extra. The royal court always sought to pay a little more than the average client, which means that 1910 was a particularly profitable year: Schwartze raked in princely sums for a portrait of Princess Juliana as a baby and also a full-length of Queen Wilhelmina. (Schwartze painted so many members of the royal family that she became almost a member of their household.)

Schwartze’s high prices, flair for public relations, and active role in public life through various official posts elicited both admiration and resentment. She remained much in demand as the Dutch elite’s leading portraitist right up to her death in 1918, by which time—of course—World War I had changed the tenor of European art forever.

Cora Hollema holds a master’s degree in sociology. She works as a freelance writer and has curated numerous exhibitions, including a Schwartze show at Zeist Castle (1989-90). Having already published a Schwartze monograph in Dutch, she has produced an English-language version, Thérèse Schwartze: Painting for a Living, Printed in a limited hardcover edition, this 196-page volume (ISBN 978-90-824064-1-2) can be ordered for US$70 with free shipping via www.thereseschwartze.com. Image TOP: Maria Catharina Ursula (Mia) Cuypers, 1886, pastel on paper, 28 x 22 in., private collection, photo: Thijs Quispel