Venice is an impossible city. Not just metaphorically: though it is impossibly beautiful, impossibly romantic, impossibly unique. But it is also literally impossible. Refugees from nearby cities like Padua, Treviso and Altino fled into the lagoon islands in the fifth century and their descendents elected the first doge, Paolo Lucio Anafesto, in AD 697. Their settlements, safe from Germanic and Hunnic invaders, still exist, and the ‘Queen of the Adriatic’ is now a world-famous city—but barely 55,000 people live in the Centro Storico, the central city.

That is, by European standards, tiny. It’s the size of Margate, or Bangor, or Widnes. Yet it is one of the world’s top 50 tourist destinations, welcoming more than five million visitors each year before the covid pandemic. It tops bucket lists for countless couples, and it hosts one of the most significant international cultural fairs, the Venice Biennale.

The Biennale started in 1895, and its last pre-pandemic edition was May You Live In Interesting Times, curated by the American artist Ralph Rugoff. The scheduled 2021 exhibition fell victim to covid, so this year’s gathering was the subject of intense interest, a demonstration that the art world was back and open for business. (Business is the operative word: although sales have been prohibited since the 1960s, it remains a key event for artistic promotion and coincides every other year with Art Basel, the biggest modern and contemporary art sales fair in the world.)

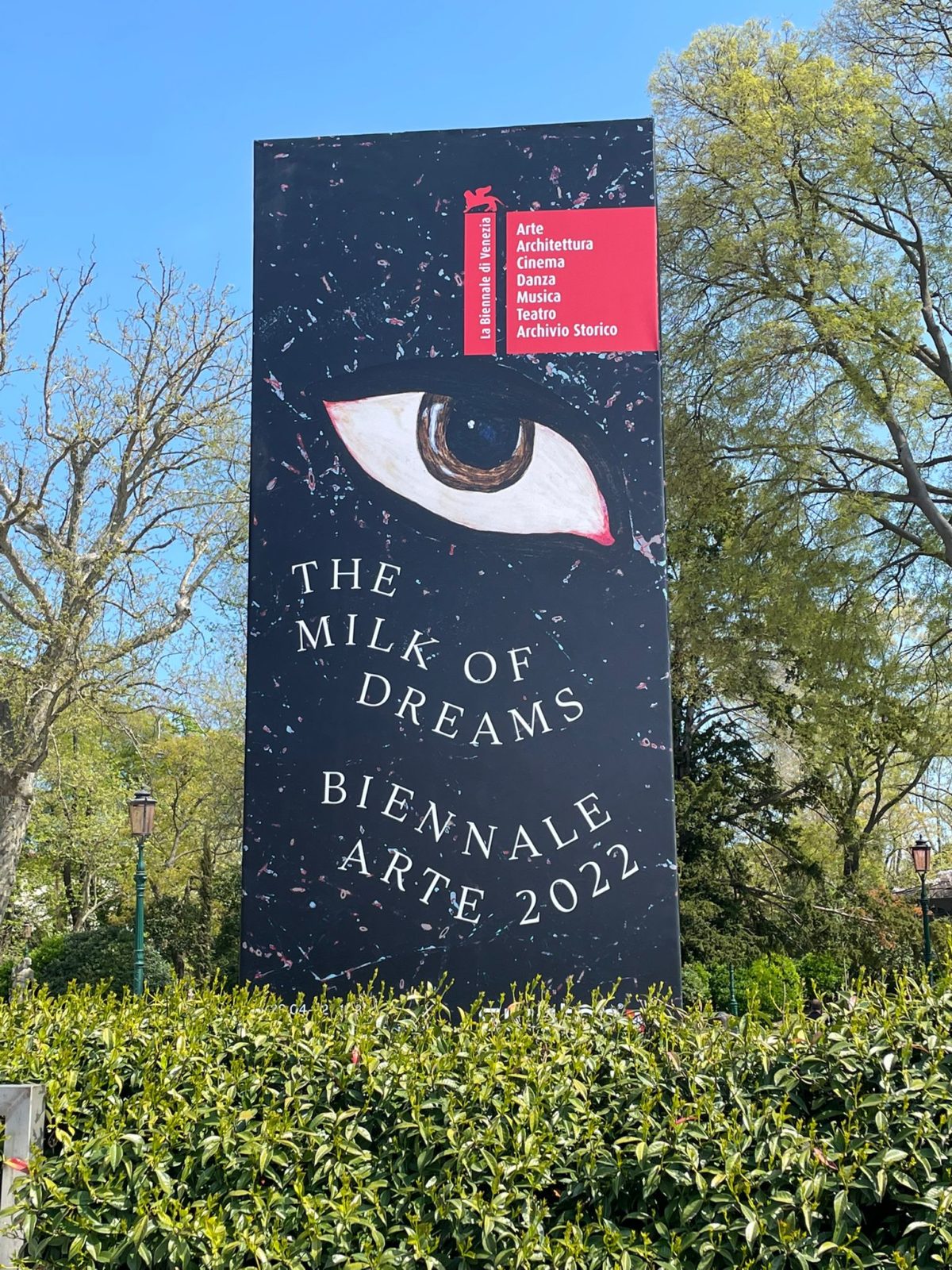

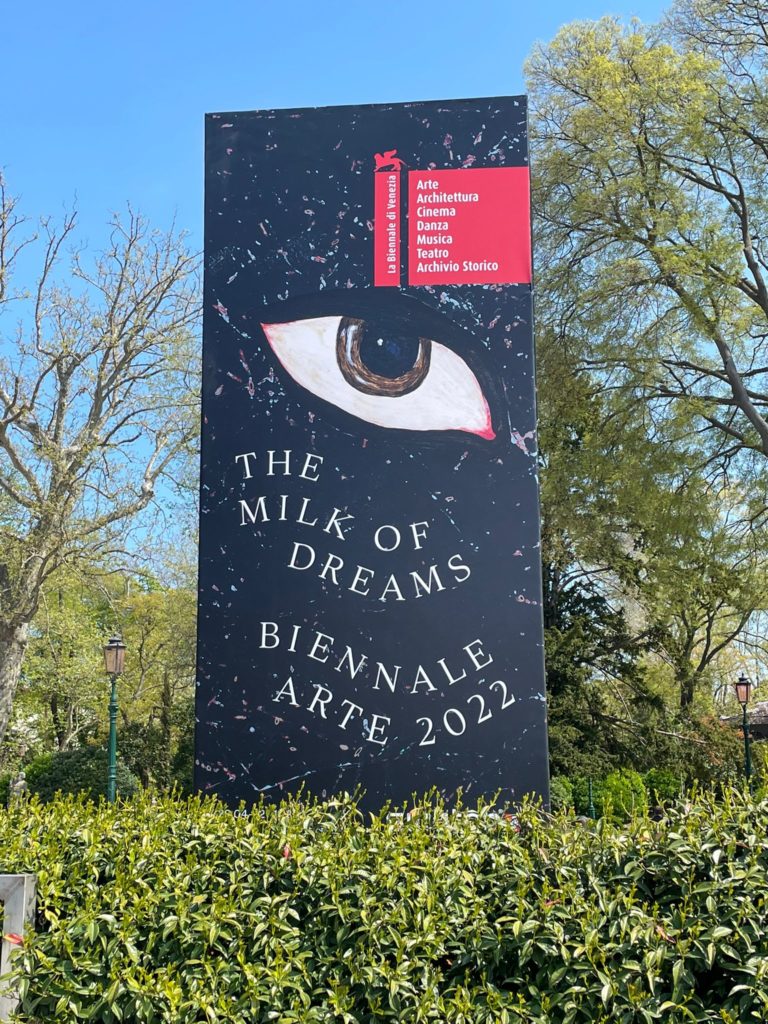

This year’s Biennale is curated by Cecilia Alemani and is entitled The Milk of Dreams. It takes its title from a book by British-Mexican surrealist Leonora Carrington, an illustrated tale of origins in an untethered, unrestrained world, but one which also describes the unbearable pressure on the individual; this mirrors Carrington’s own life, marked by confinement in psychiatric institutions.

The idea of reinvention under pressure was central to Alemani’s vision for the Biennale. The world lies, by common consent, at a critical point, emerging from a deadly pandemic which has killed more than six million people worldwide and continues to exact its fearsome toll. How can the world of art play its part in this rebirth, how can it help the world articulate its response to the pandemic?

This is what art does. It is not simply for show, for aesthetic delight: it gives us a visual, verbal and emotional vocabulary to process our feelings, to explain to us what we know but cannot express. Good art does not simply show but it unlocks, reveals and interprets.

The main site of the Biennale, the collection of national pavilions, is at the Giardini, on the shore of the lagoon. In the April sunshine, it is a magical site, a kind of world in miniature, the pavilions like the islands of Venice itself. There are 30 of them, 29 for favoured nations and the Central Pavilion itself, built in 1894. Walking around the Giardini before it opened to the public—but still humming from the presence of eager critics—felt like stepping into a new (but also old) world, culture emerging from its chrysalis, or perhaps from suspended animation.

The quotidian world of events intrudes into this artistic idyll. The imposing Russian pavilion is closed and shuttered up, the régime of Vladimir Putin being persona non grata after the invasion of Ukraine in February. The Israeli pavilion wrestles, as it always must, with the identity and reputation of the Jewish state, while the Nordic countries have pooled their capacity into a Sami exhibition, showcasing the lifestyle of the indigenous people of Scandinavia and the existential threat they face from the encroachment of modern economic life.

For all that, the 2022 Biennale remains an intensely and fundamentally human experience. To quote the curator, Cecilia Alemani, it is intended to:

Sum up many other inquiries that pervade the sciences, arts, and myths of our time. How is the definition of the human changing? What constitutes life, and what differentiates plant and animal, human and non-human? What are our responsibilities towards the planet, other people, and other life forms? And what would life look like without us?

Its three themes—the representation of bodies and their change, the interplay between humans and technology, and the connection between bodies and Earth—bring us back to the questions we are forced to ask ourselves about the post-covid world. What are we here for? How do we react to such a widespread global event? How can we make ourselves both more resilient and more sustainable?

Art cannot answer these questions in their entirety. But it can, will and should step into the gap to show us the way to answers, reflecting the human spirit back at us but also shining a light forwards to our onward journey and, perhaps, to our progress.

The Venice Biennale opened to the general public on 23 April. It runs through most of the year and will close on 27 November. Reviews of highlights, lowlights and quirky moments will follow in this journal.