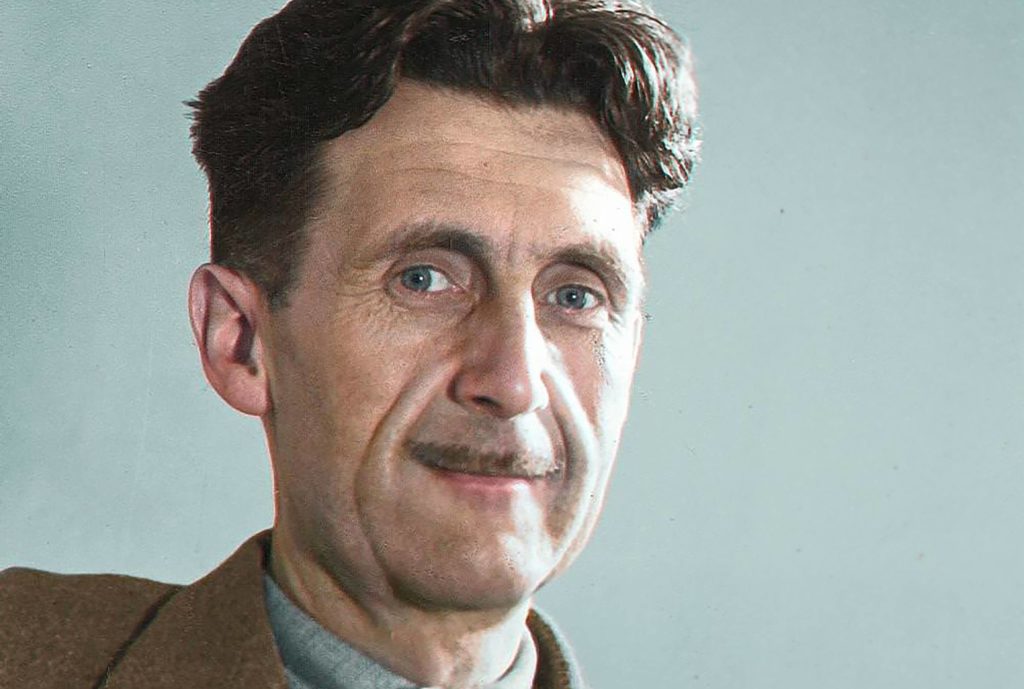

Something is distilled by the wilderness which surrounds Barnhill. The house in which George Orwell wrote the seminal novel 1984 sits at the northern end of the Hebridean island of Jura, an hour’s drive and then a 90-minute walk from the small ‘town’ of Craighouse at the south end of the same eastern coastline. Walking the farm track up to Barnhill you’ll pass cattle, gently rolling hills and cotton grass. In the summer sunshine, looking back over the azure sea to the Mull of Kintyre, the landscape feels dreamt—almost painted—with its richness of colour. In mid-winter, no doubt, the bleakness and exposed “ungettable-at”-ness that Orwell describes would have given a sense of trepidation, almost foreboding.

If you do take the journey, the best way to view the house is not up close but from the winding track that snakes down from above the hill and the ruined sheep corral, giving you a view of the lea in which Barnhill sits and the tidal race over which it looks. We were incredibly fortunate to be granted special permission to visit the house which is privately owned, and found a dwelling still much as Orwell would have known: there is no mains electricity nor central heating, and the walls are still mostly wood-panelled, giving a parsimonious but not uncosy feel throughout. Orwell wrote in the upstairs bedroom, often from his bed, but sometimes at the window overlooking the barley field that was in front of the house and the swirling eddies running down the sound of Jura.

His diaries from his years there reveal a sense of peace wholly at odds with the other work he was writing at the time. His interest in nature is omnivorous: he notes birds, rabbits, snakes, deer and the gamut of British flora. He works hard on being subsistent: detailing his fruit crops, digging potatoes, turnips and carrots; he has luck fishing for saithe but less so with his lobster creels, and notes a shark he sees from the ferry while crossing to the mainland.

Ask around today and there are still stories on the island from his time there: a tall man riding a motorcycle on the unforgiving road (there is only one) and sharing the time of day and a dram (always a double) with the postman. By all accounts he was a liked, if private, man; not quite a recluse but highly valuing his disconnectedness and independence. He was ill though. It was necessary to burn the sheets of his bed when he stayed at neighbouring farms due the the risk of infection from the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him in London’s University College Hospital in 1950. The day after he passed, his sister Avril and adopted son Richard, then five, first heard the news in Barnhill’s kitchen when listening to a BBC radio broadcast.

Walk for another hour or so north of Barnhill and you’ll pass Jura’s ‘last’ buildings, former farms now abandoned, before venturing up and over the boggy heaths. At the top of the island is the Gulf of Corryvreckan that, between Jura and Scarba, mashes the racing tides and currents above an underwater stack, resulting in the infamous whirlpool or ‘maelstrom’: one of the largest and most dangerous in the world. On returning from picnicking on a remote beach on the island’s western coast, Orwell nearly drowned there. After he allegedly misread the tides, his boat lost its outboard motor and he, Richard and his nephew Harry ended up on a nearby island after the boat capsized. As Richard told The Daily Record many years later, “We scrambled to the land and were picked up by a lobster boat. It could have gone badly. The tide was running and we could have been dragged away and been drowned. There would have been no 1984.”

Tides of time

It’s tempting to think of Corryvreckan’s tempestuous tidal races as a metaphor for the dystopian violence depicted in 1984, but what feels more telling of Orwell’s time on Jura—and perhaps the contrast fed his thought process—is his celebration and appreciation of the natural world and his very individual interactions with it. In his life there, we see nothing of the crushing, total power he depicts in the novel. It is a very quiet, cherished freedom, that although played out on the delicate fringes of civilisation—and of Orwell’s own mortal coil—is poignant.

Like so many millions, I found his work seminal in forming my understanding of society and the world. This was not because I knew that Big Brother was bad, but that power structures, in seeking their own justification, are at best clumsy and at worst abhorrent. In such parameters their narratives, usually deliberately, suffocate intellectual liberty. Orwell knew this. His depiction of the myth of an enlightened and civilised British Imperialism in Shooting an Elephant and Burmese Days, is better than most journalism from the time. In A Clergyman’s Daughter, in the heart of a middle England home the beleaguered Dorothy comes across “a little sandalwood box labelled Piece of Bread touched by Cecil Rhodes at the City and South Africa Banquet, June 1897”. That satire still speaks today.

Orwell’s own life reflects his belief in liberty as much as his writings. Disillusioned with the Indian Imperial Police, he leaves to become a writer, he lives as a tramp, he fights fascism in Spain and is shot through the throat doing it, he then witnesses Stalin’s purge of the communists fighting for the Republic and has to flee before the Soviet agents come for him. He was by no means a passive observer: his detailing of daily life, his own and the lives of his characters, gives his work a perennial, very human appeal: stories abound of those behind the Iron Curtain being incredulous that 1984 could have been written by someone who had not suffered daily life in the Soviet Union.

When the Soviet state finally collapsed seven years after 1984, liberty had, to an extent, won. People did not have to live in fear, and ideology had lost its long trial against society. However, a generation later, we are still experiencing the manipulation of information and truth to coerce, divide and control. While all these modern phenomena, from state sponsored digital disinformation to fake news to truth erosion, deserve their own unique examinations and redress, the routes to power taken via manipulation of information are the same ones Orwell witnessed and wrote about. Doublethink is real: in Myanmar today Orwell’s critique of the excesses and moral short-comings of British imperialism, Burmese Days, is sold abundantly. 1984, on the other hand, is essentially banned—as if the books are not connected, as if the state is admitting something beyond its own obtuseness.

Donald Trump sits perfectly in the ‘Orwellian’ prism. He encourages violence, alludes to an imaginary period of ‘greatness’, uses childish language to describe other states and peoples, lies in the face of compelling evidence and unashamedly traduced his own authority via Twitter. The only thing that matters to him is the narrative, truth is merely an ephemeral and unwanted by-product. Trump’s legacy will be the fear he has instilled in comfortable liberals by showing them how easily all semblance of decency and integrity are removed from power. Ultimately, he is refusing to be responsible by denying the reality in which he operates. In Britain today this disconnect is wantonly championed by the intellectual cowards who have taken over the Conservative Party.

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Orwell wrote consistently on the erosion of objective truth—a process continued today by those who believe in ‘alternative facts’. In 1942, he wrote the following passage in retrospect of his time in Spain, having told a friend “history ended in 1936”.

A British and a German historian would disagree deeply on many things, even on fundamentals, but there would still be a body of, as it were, neutral fact on which neither would seriously challenge the other. It is just this common basis of agreement, with its implication that human beings are all one species of animal, that totalitarianism destroys. Nazi theory indeed specifically denies that such a thing as ‘the truth’ exists. There is, for instance, no such thing as ‘science’. There is only ‘German science’, ‘Jewish science’ etc. The implied objective of this line of thought is a nightmare world in which the Leader, or some ruling clique, controls not only the future but the past. If the Leader says of such an event, “it never happened” – well, it never happened. If he says “two and two are five – well, two and two are five. This prospect frightens me more than bombs – and after our experiences of the last few years that is not a frivolous statement.

Looking Back at The Spanish War Autumn 1942 (published May 1943)

In this world, the ‘fiction’ Orwell was creating in his bedroom in Barnhill has an indelible importance.

All the confessions that are uttered here are true. We make them true. And above all we do not allow the dead to rise up against us. You must stop imagining that posterity will vindicate you, Winston. Posterity will never hear of you. You will be lifted clean out from the stream of history.

1984

Asking Orwell’s ghost to tell us what he would have thought of our world today is not the point, but we must accept that the work of 1984 is never finished. The book is not a warning, it is an acknowledgement. The liberty and very English ‘decency’ that Orwell craved are to be fought for everywhere, against totalitarian ideas that deny the pluralism of the world. Today, that fight is in football crowds and on social media, but it is also a fight that should define us as free-thinking individuals, able to speak with, and for, truth in a world of informational currents that are much more numerous and much stronger than any Orwell encountered.

In 1944, Orwell’s column for Tribune detailed the good luck he had had in his garden with some rose bulbs he had bought from Woolworths before the War. It is easy to imagine the alleged outrage the column created: how could he write about something so frivolous at such a time? Orwell’s anecdotal response, or certainly his purpose for writing about rose bushes was that, at such times, these words on nature were more, not less, important. He almost certainly meant simply to remind us that, even in the darkest times, there is good and beauty in the world. However, reading these lines almost 80 years later, it is striking how they hold a beacon to individual thought and perspective—to small liberties and small, but telling, truths: something every bit as beautiful as the roses he describes or the Hebridean wilderness that surrounds Barnhill.

Alex Matchett is the editor of CulturAll