Hannibal Lecter, Thomas Harris’s murderous but sophisticated psychiatrist, is probably one of the most recognisable villains in cinema history. Sir Anthony Hopkins immortalised the doctor in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs, and went on to reprise the roles in Hannibal and Red Dragon. He even has an origin story in the wilds of wartime Lithuania, which seeks to explain how he became what he did.

His first appearance on celluloid, however, was not in via Hopkins but that other British cinematic heavyweight Brian Cox, who took the role of “Hannibal Lecktor” (sic) in Michael Mann’s stunning 1986 film Manhunter. Hannibal is neither the star nor the chief villain but somehow casts his pall over the whole enterprise.

Thomas Harris unleashed the world of Lecter in 1981 with his novel Red Dragon, of which Manhunter is a free adaptation. At the initial planning stages, the film was to share the book’s title, but Dino de Laurentiis, whose DEG Group was in charge of production, worried that the relative failure of Year of the Dragon, the noirish crime thriller made by Michael Cimino in 1985, would taint anything associated with dragons.

Mann created an icon of 1980s sensibilities. William Petersen (later to find fame in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation) leads the cast as troubled but intuitively brilliant FBI Agent Will Graham. We see him at first in a wide shot of a Florida beach, perched on driftwood, while his former boss, Jack Crawford (the reliably superb Dennis Farina) implores him to come back to work to catch a new and deadly serial killer who strikes every full moon. The image of wide, clear blue skies and near-white sand is stark and brilliant, showing us the paradise to which Graham has escaped. (The below contains plot details.)

Escaped? Yes: the FBI agent was responsible for catching and arresting Hannibal Lecter in a duel of wits which will resurface, but he was badly injured and left with terrible psychiatric wounds too. Now he lives in peace with Molly (Kim Greist) and young Kevin (a brilliant David Seaman), fencing in a turtle hatchery and messing around in boats. The palette is paradisiacal, Greist a vision of blonde curls and white linen, so that we are left in no doubt as to what Graham will be leaving behind if he heeds Crawford’s call.

The villain whom the FBI are desperate to catch is as savage as he is mysterious. He kills on the full moon, and he has slaughtered two families, the Jacobis in Birmingham, Alabama, and the Leedses in Atlanta, Georgia. The killings are violent and sexual: parents and children are murdered then the women violated, all having shards of mirrors inserted into their eyes so that (it turns out) the killer can watch himself at work. Bite marks on the bodies have led the police to nickname the killer “The Tooth Fairy”.

There is never any doubt that Graham will agree to help, but Crawford promises to keep him at a safe distance; he simply wants his extraordinary empathy (there is no other word for it) for the most damaged psyches to help understand, predict and identify the Tooth Fairy. Crawford knows the clock is ticking until the next full moon.

Graham visits the Atlanta crime scene, and we are given a harrowing insight into the sheer violence of the crimes. There is blood everywhere: Graham says into his dictaphone, “Even with his throat cut, Leeds tried to fight because the intruder was moving to the children’s room,” a dry observation which is as stomach-churning as it is heart-breaking. We hear that Mrs Leeds was shot in the stomach but lived for another five minutes or so, conscious of the devastation of her family.

It is the twitching, nervy persona of Petersen’s investigator which drives the film. He knows, as does Crawford, that to understand the killer he will need to push himself to dark places, and he smokes constantly. Clad in an ’80s wardrobe which would have been perfect for Mann’s TV masterpiece Miami Vice, he stalks around hotel rooms and gradually absorbs the horrors, peeking into the disordered mind of whoever has committed these brutal crimes.

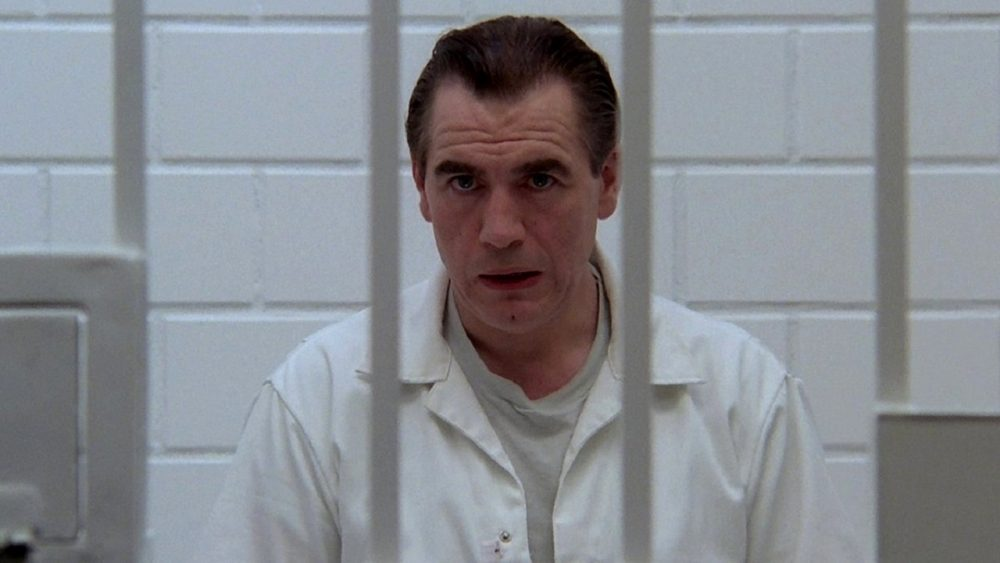

To reawaken his detective skills, Graham decides to visit Hannibal in the secure hospital in Baltimore where he is confined. Everything is clinical and bright white—there is none of the schlocky dankness of The Silence of the Lambs—and it is here that we meet Scottish actor Brian Cox as the homicidal and cannibalistic psychiatrist. Hopkins made Hannibal a Grand Guignol figure, all campy twirls and sinister politesse, but Cox took a very different approach. The doctor is dressed in a pressed white prison jumpsuit, and greets Graham conversationally, almost warmly. But the menace oozes. His eyes flicker menacingly and the destructive power of him, the horrible awareness of what he has done and could do, is frighteningly apparent.

It is an uncomfortable encounter. Graham knows the risks he is taking by exposing himself to Hannibal again, and the audience sees how fragile is the recovery he has made. He is wary and cautious, and Hannibal can sense weakness. The verbal sparring is fearsome to watch. Hannibal goads Graham, saying that the FBI man must think, since he caught the psychiatrist, that he is the smarter.

“I know I’m not smarter than you,” Graham says flatly.

“Then how did you catch me?”

“You had disadvantages.”

“What disadvantages?”

“You’re insane.”

The audience may laugh, and the line is objectively funny, but what are its implications? Hannibal presses them home.

“The reason you caught me, Will, is we’re just alike.”

[Spoiler alert]

Cox is superb. Outwardly unprepossessing, he makes it very clear that he is capable of anything, and his mind moves preternaturally swiftly and with intense cunning. Graham squirms, as well he might, not only because Hannibal can seemingly read him with ease but also because there is a grain of truth in what he says. The Scottish actor based his performance on 1950s Lanarkshire serial killer Peter Manuel, portraying Hannibal as a man who simply doesn’t care about right or wrong. Knowing that his vocal work would be critical to the character, he auditioned with his back to the casting agents.

We are well into the film before Mann unveils the Tooth Fairy, in the guise of Francis Dollarhyde, a tall and socially awkward man who works in a film developing lab in Gateway, Missouri. He is played by Tom Noonan, who stayed in character all the time he was on set and did not meet Petersen until the filming of the story’s climax. Noonan, tall and muscular (he weight-trained to bulk up for the part), is an outsider. He speaks slowly because of a cleft palate, covering his mouth with his hand when he does so. It makes him shy and unapproachable.

A tiny glimmer of redemption is offered when he meets blind co-worker Reba McClane: unable to see him, she nonetheless hears the hesitancy in his speech and is blunt with him. It opens him up, and a romantic relationship quickly develops.

The orderlies in charge of Hannibal discover a letter from the Tooth Fairy to their charge, written on toilet paper with a bite mark confirming its provenance. The FBI discover that the two monsters will communicate through the personal ads in the National Tattler, a tabloid whose star reporter, Freddie Lounds (Stephen Lang), has history with Graham: he sneaked into the hospital where Graham was being treated after his arrest of Hannibal and photographed the stab wounds in his abdomen. Now he outs Graham as being involved in the Tooth Fairy case, exposing him in the way he had promised his wife would not happen.

At this point the film takes a turn which is, if possible, even darker. Graham’s family are spirited away to safety, and he must leave Molly and Kevin. Now he realises the depth of the battle he is in with the Tooth Fairy. Graham understands that they must both now go to a very dark place, one which leads inexorably to a climax, and one from which only one of them can return. It is now one-on-one. As Graham says bitterly to him, “Just you and me now, sport,” the last word spat out.

Lounds (who was played by the great Philip Seymour Hoffman in the 2002 remake Red Dragon) is simply a pawn in all of this. When the FBI plants a story in the Tattler, Lounds is kidnapped and brutally murdered by the Tooth Fairy. Meanwhile the FBI is unable to break the code between the two killers, and the personal ad is allowed to run. When they finally decipher it, it is chilling: it gives Graham’s home address and tells the Tooth Fairy, “Kill them all—save yourself.”

It is Graham’s extraordinary intuition which breaks the case. Watching the home movies of the two slaughtered families, and musing that the Tooth Fairy is primarily motivated by visual imagery, he realises that the killer must have seen these very movies themselves. They are quickly tracked down to the laboratory where Dollarhyde works, and the killer’s identity revealed.

So we come to the film’s nerve-jangling climax. The police rush to Dollarhyde’s house in the foggy reeds outside St Louis, but it is Graham and Crawford who arrive first. Crawford urges Graham to wait for the SWAT team, but the investigator sees that there is a woman, Reba, inside with Dollarhyde whom he is about to kill. There is an assault on the senses. Inside is playing, at deafening volume, In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida, Iron Butterfly’s dark, dense, brooding rock masterpiece. Graham is determined to stop the Tooth Fairy’s murderous exploits and runs towards the house, hurling himself through the full-length kitchen window. He is brushed aside by Dollarhyde, who kills several policemen coming to assist, but pulls himself together just in time to shoot the Tooth Fairy again and again.

At last the seemingly invincible killer is felled. Hit by several Glaser Safety Slugs, which house birdshot suspended in liquid Teflon and cause devastating wounds, he collapses in a pool of blood which fans out like wings.

Michael Mann directs a masterpiece of tension and wrings outstanding performances from his fine cast. But mention must also be made of director of photography Dante Spinotti, who gives the film its inimitable aesthetic. As well as the Mann signature blue tint (see his 1995 Heat), there are distinctive 80s colours to several scenes, with the stark azure-and-white of the Florida coast to the bleak “neon angst” running through the film.

The soundtrack is also first-rate. The Prime Movers, Red 7 and Shriekback deliver nerve-jangling synthesiser classics: This Big Hush is a creepy, hoarse ballad guaranteed to make hairs stand on end, while Strong As I Am is a rage-fuelled anthem which soundtracks Dollarhyde’s fury.

Manhunter is an ineffably 80s film but this, strangely, does not date it but marks out its extraordinary strength as a feature. Michael Mann creates his own world, with its own palette and soundtrack, angsty, moody and frightening. His cast delivers first-rate performances, and William Petersen, as the handsome but haunted FBI agent, produces a career highlight.

There is not a second wasted —several scenes, like Hannibal’s childhood and an exploration of Graham’s trauma, were stripped out as extraneous—and the result is a taut, scalpel-sharp thriller which burns itself into the consciousness.

Box office returns in 1986 were not especially high. But Manhunter is an edgy and stylish classic. More than just a police procedural or serial killer yarn, it peers into the darkest parts of the human psyche. It is a mighty two hours that any fan of cinema should watch again and again.

[This review is dedicated to my father, Leonard Wilson (1948-2017), who loved Manhunter as one of his favourite films, and celebrated it above all the subsequent Lecter iterations. I hope that by writing this, I have shared his passion for serious and compelling cinema.]