What were the social legacies of The Crusades back in Europe?

I’m so glad you’ve asked that. It is a question that doesn’t get asked enough. One of the “lores” to the Crusades, is that it is “just warriors”, “the goodies vs the baddies” – weapons and battle and everything you get in computer games – that’s just the military aspect of the Crusades. But that’s never been the call for me. The call for me is quite dark, it is about money. It’s about the waxing and waning control of the Papacy, it’s about political allegiances and it leads to genocide on huge scales.

The social impact is so important. When you think that the annual income of a country was being spent on a single crusade. Just in terms of the personnel it would be akin to World War II in that there would be no young, strong men around and when you remove those people, society grinds to a halt in many respects: women, the elderly and children can continue to run a state as far as they can. But crops can fail, harvests can go, you have no one to protect you so outlaw behaviour and criminal behaviour all increases. It’s deeply destabilising to take thousands of young, healthy, fit men and basically send them to either slaughter or to be gone for long periods of time. So yes, deeply disruptive and not a nice time to live through.

You mentioned the genocide, what specific examples are there?

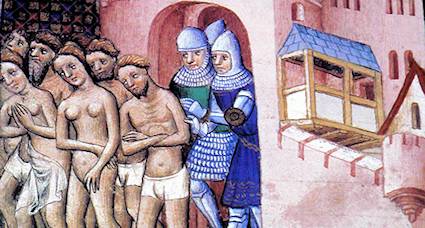

The attacks on Jews are well known, so through most of the Crusades there is a huge decimation of Jewish areas, Jewish populations, thousands and thousands either killed directly or driven to suicide through poverty and being hounded. So that was sort of the “first wave” but you have so many examples of persecution against so many different groups. I’m working on the Cathars at the moment. They were thinking differently but they were impoverished, they were a sect if you like and they were extreme and aesthetic but they weren’t any major political threat. And yet the Papacy decided they had to be annihilated and it was a complete annihilation.

One of the famous stories about a particular attack on the Cathars is about a particular town [Béziers], full of thousands of people where the soldiers were saying “How do we know who is a Cathar and who isn’t? We might be killing innocent Christians, we might be killing good honest people.” The bishop just says: “Kill them all, God will know after death who was right and who was wrong.”

There is an absolute blind murdering of people and it is happening all over through the Crusades. As you move thousands of people, you displace thousands of people, you antagonise thousands of people so, it is all about death and displacement. That’s a negative way to talk about the Crusades but it’s the human side.

Was it simply “you’re either with us or against us”? Or were their political motivations to find scapegoats, or all of these things?

Absolutely, their political machinations are totally underpinned by money. That’s what you learn about in Lost Relic Hunters. There’s such a huge amount of investment in the Crusades that certain rulers and states, like the Venetians, were vulnerable to bankruptcy. They have to take something back and that leads to Christians turning on Christians and it becomes very indiscriminate. Even from the beginning [there is catastrophe]. On the People’s Crusade, possibly a hundred thousand people met their death; this was all on the strength of Pope Urban II’s rousing political speech.

I mean, it is horrible when you think about it. If it was playing on now, and we watched this, we’d see a maverick leader fire up a group of people through their words and then send them off to death and disruption. We get small versions now but this was on a different level.

What happened to The People’s Crusades? People just went up and starved obviously, because there was nothing to provide?

But also massacred. At various points, as they are moving across towards the Holy Land they are losing lots and lots of people to famine, travel, they are being attacked, they are being picked off, and finally there is a battle and just a massacre. Only, I think, 3,000 people got out.

What happens on the Fourth Crusade and the Sacking of Constantinople in 1204?

The sacking of Constantinople is really problematic because is the moment where Christians turn on Christians, but it is not unprovoked. There has been all sorts of insults and promises of armies and promises of support that haven’t materialised; it’s a building antagonism and it finally spills over. But I think the symbolism of it is not dissimilar from the huge symbolism of the sacking of Rome [in 410 AD], in that it is something nobody ever thought possible.

That’s what happens in the sacking in Constantinople – and it is astonishingly brutal and all I can think of is that it got out of hand. Human excess took over, greed and that destructive barbaric element of humanity just destroyed the city. There are moments in history where that happens and they are pivotal moments. As a historian I tend to think of history as a fluid set of gentle waves, sort of moving along. There are very few moments where there is a line in the sand and you go “wait, we’ve woken up in a new era!” but there are those occasional moments such as this and the Battle of Hastings, that are pivotal. Things like the Sacking of Constantinople change the world.

When you get those big moments, I think to live through them must be utterly traumatic. We are having a taste of trauma, at the moment. But these traumas I’m talking about are cataclysmic. The effects of Black Death: cataclysmic, the effects of the Crusades: cataclysmic. So, it’s keeping these things in perspective I think.

Was there major antagonism towards the Orthodox church before that or was the Sacking of Constantinople more down other machinations of the Crusades?

There have always been antagonisms between different strands of the Church. When I do Medieval Art with my students I say “Are you looking forward to it?” and they say “No, it’s all going to be about religion and the church… I hate the church!” And then I try to explain to them, that even that term “The Church” is a nonsense. There is a set of powers that represent ideologies that are constantly shifting, so the Christian church in the year 500 is completely different from the one in 900, or that in 1200. They morph and change their basic ideas on a regular basis. And you have schisms, you have an anti-pope, and you have the Orthodox Church. And all of these things they are all part of Christendom but it is a little bit like saying “The Celts” which is a term for an entire geographic region of people. They would have hated the people at their doorstep, maybe more than any other exterior enemy and one group of Celts would have disliked an other group of Celts hideously. It is the same in Christianity. With Western and Eastern bishops it has never been a happy relationship. But I think, in terms of The Crusades, it is not really about the church, it is not really about a difference in belief. A line has been crossed but it had been crossed before, people talk about Christian turning on Christian but the Cathars were Christian, there were many other sects and heresies that were persecuted but Constantinople was just on such a big scale and it was justified entirely by greed.

On the new series of Lost Relic Hunters: collector Hamilton White is described as “in a league of his own”. Is he, and are all his pieces original? Are we seeing more amateur historians and is this a good thing?

It was really amazing meeting Hamilton for the first time. He is an unusual character but he is so like me in that shared love of historical objects. I love handling objects from the past and he is the same and it goes right back to his childhood and his very early coin collections. He is obsessive about connecting with the past through material culture and so it was lovely.

He is a detective, and he wants to hunt these things down. I think there is nothing better than that: I was a young archaeologist, I joined young archaeology clubs, getting in the ground, seeing where the artifacts come from and having a go with the metal detector, just thinking of it in your own garden, finding something, it doesn’t have to be something expensive but it is something from the past and as you hold it you’ve got a little window, there in your hands to a time that is gone. It is like a mini time machine. So I couldn’t encourage children enough. But also visit museums, go and see the real deal. Go and see the really good ones, and don’t just see them as priceless objects and think “I could never afford this, this belongs to the elite or the rich”. It is not, they are for everyone and they will take you on a journey if you take time with them.

I was in Crete’s Palace of Knossos, working with an archaeological team there and a guy handed me this little tiny drinking cup and it just looked like a plastic cup for us today. He said “look at this” and there was a great big thumb print. He said “put your thumb there, you’re touching the hand of someone four thousand years ago!”

What’s the most remarkable relic or historical object you’ve come across?

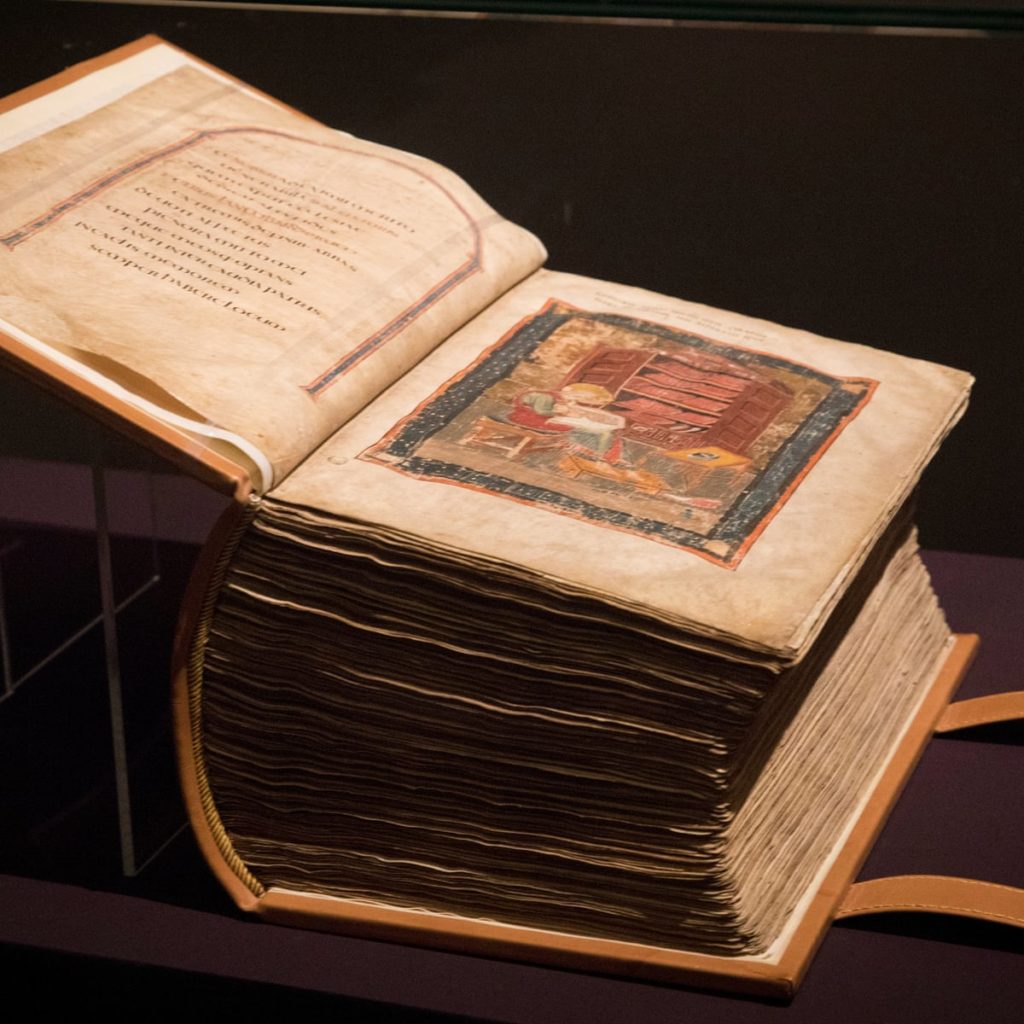

Wow! Hard… I’m going to go with The Codex Amiatinus, which is the oldest single bound copy of the Bible in existence. It is in Florence but it was made just outside Newcastle in the monastery of the Venerable Bede. He and the first-generation converts converted from Anglo Saxon pagans and from this world of Odin they needed to learn about the word of Jesus in the Middle East – though they were up in Newcastle.

The monastery was all glass and plaster and painted pink and inside this building the abbot collected the finest relics, the finest artworks, the finest bits of scholarship from all over Christendom. He was constantly travelling, picking up books, picking up art, picking up information and bringing it back to this monastery, where this little boy Bede grows up and fills his brain with all the knowledge.

In this remote northern space, they set a project to making not one but three single codex Bibles. It would have been like being at Silicon Valley during the development of the microchip. And they have to get their hands on all this information and they have to get the personnel to get this thing written. They needed a thousand calves, for the skin, for the vellum, to make each one. So that is three thousand calves. The one that survives, weighs the same as a Great Dane dog. So to lift it takes two men – it is enormous…

My dad worked in Silicon Valley when the microchip was being invented. He came home with a prototype and he had it on his finger. I was really young, and he said “Look at this. This is going to change the world”, I remember thinking “What? What is that? Rubbish”. But he was right: it’s when computers went from filling up rooms to being at the end of your fingertips. And that is how I feel about the Codex Amiatinus. It is one of those objects that changed how everything was done from that day onwards.

Dr Janina Ramirez appears in the latest series of Lost Relic Hunters, airing on Sky History on Mondays at 9pm

Her forthcoming book Femina is available to pre-order here.