There are the immediate, compelling things about which we care. Has my granny had her jab? Is my daughter being bullied at school? How long will I be on hold before I can sort my internet problem?

Beyond that front row, there are things that, if we have time or a quiet Saturday morning when our thoughts are less reactive, we might consider.

They’re less in-your-face, more a thought luxury, but when you think of them you realise that maybe they’re not a luxury, they’re not the icing on the cake, they’re the cake.

One of those things for me is looking. As I’m lucky enough to have good eyesight, I see all the time. Looking, that binocular encounter with the world, is on tap. Effortlessly, like electricity, my eyes power my life. They are an outward miracle of sorts.

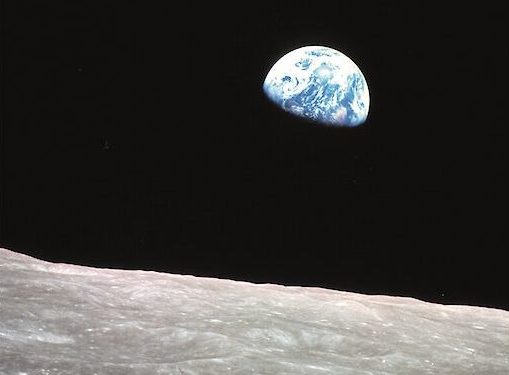

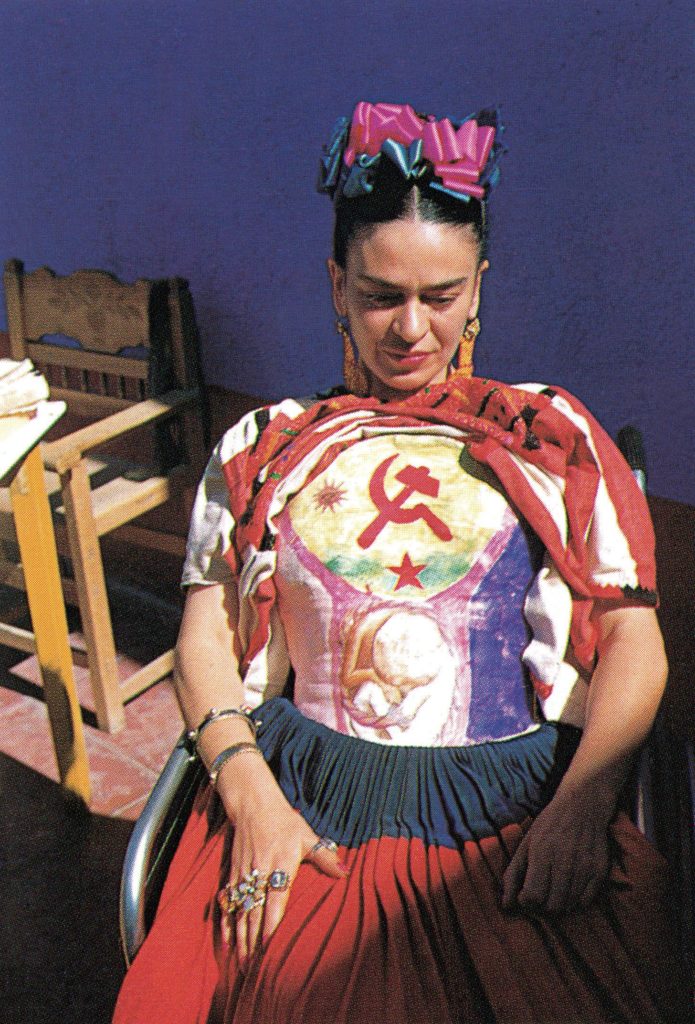

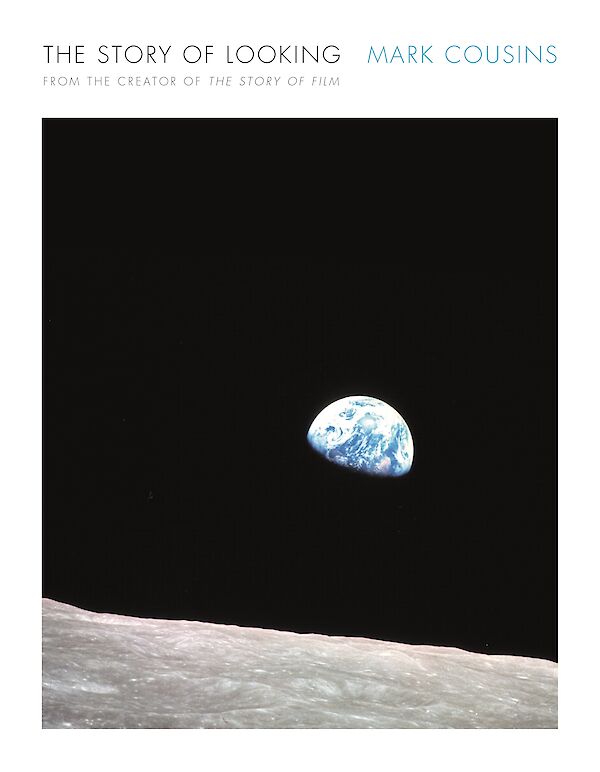

It seems obvious to say, but most aspects of life relate to this miraculous paradigm: Andy Murray’s split-second analysis of the trajectory of a tennis ball as it comes barrelling at him; Christopher Columbus’ first glimpse of what he thought was India; Frida Kahlo’s painting and repainting of her own body; anatomists’ dissections; the images beamed from the Mars Perseverance rover; Haussmann’s redesign of Paris; David Bowie’s Heroes (inspired by a glimpse of lovers at the Berlin Wall); Albert Einstein seeing the Bern clock tower and a tram and, as a result, coming up with the idea of relativity; the films of Agnès Varda. In sport, conquest, art, astronomy, urbanism, music, physics, cinema and so many other fields, looking is an initiator or enabler.

We are used to the idea of our work lives and our love lives, but when we say that we have looking lives, the world reshuffles. History reshuffles.

I’ve been thinking about this recently for two reasons. The first was in order to write a book, The Story of Looking, in which I tried to write about the reshuffle. The second was because my eyesight suddenly worsened. In my early fifties, I developed a bad cataract and so the visual world went milky. Like many children, I wasn’t good at verbal learning at school, and was downgraded as a result. But I did strikingly well in art, physics, chemistry, woodwork etc—our art schools, football clubs and engineering colleges are full of people like me. As I grew up, I found that looking was my rocket fuel and consolation. I became a filmmaker, and drew and painted when I felt overwhelmed by stress. The cataract meant that the lifeline, the crutch, was weakened. I was upset. In addition, I’d done a DNA test and the result said that I had one of the genes for macular degeneration. I worried that the fuzziness in my eye might be that too.

Luckily the NHS moved fast, my Bengali-British eye surgeon Pankaj Agarwal was an expert, and now I can see even more clearly. Every morning when I open the blinds, I feel that I look at the world like Frida Kahlo looked at her body—with fascination, as if it is a machine or a myth or an animal. As I write this, I can see some snow on the hills south of Edinburgh. I watch as stonemasons cut and fit sandstone to re-clad a tenement building opposite. I glimpse the ghostly reflection of my face in the laptop’s screen and wish I looked more like my younger self. I notice the colour of the hyacinths on my desk which have just bloomed—dusty pink when fully opened, but salmon and green in their buds.

Looking tells me where the horizon is, that my partner has put on her mascara, that spring is here, that the diurnal cycle continues. It is a bridge to sexuality, power and ethics.

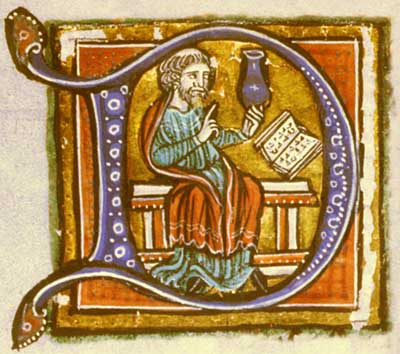

But the key thing I discovered in writing the book and undergoing my own operation was that looking isn’t wholly outward. I’m not taking visual information from the outside world into my brain and filing it away. Something less expected is happening. In Baghdad in the 800s CE, a scientist called Hunayn ibn Ishaq suggested what that might be. He said that we see because a kind of circulatory air travels forward from our brain, out into the air, bounces off objects—my hyacinths, for example—then back into our eyes. Of course we now know that there is no such circulatory air, but neuroscience has discovered that there is far more back-to-front electrical brain activity when we look than front-to-back. When I look at these hyacinths on this desk today, what I’m really doing is remembering all the previous flowers and hyacinths I’ve seen and using these previous impressions to work out what this particular pink and salmon thing is.

Hunayn was, therefore, metaphorically right. In a way we are projecting when we look. Psychologists know about such projection (traumatic flashbacks), Paul Cézanne knew about it (he was painting what he called “the optical experience developing within me”), Andy Murray knows it, and Virginia Woolf knew it (her writing is so visual and entwined with memory).

Such projection can be troubling, of course. If we tend to see what we know, it’s harder to shift dated or stereotyped impressions of people and situations. But it also means that looking is accrued and related to wisdom. It is mutual, twinned collaboration between me and the world around me.

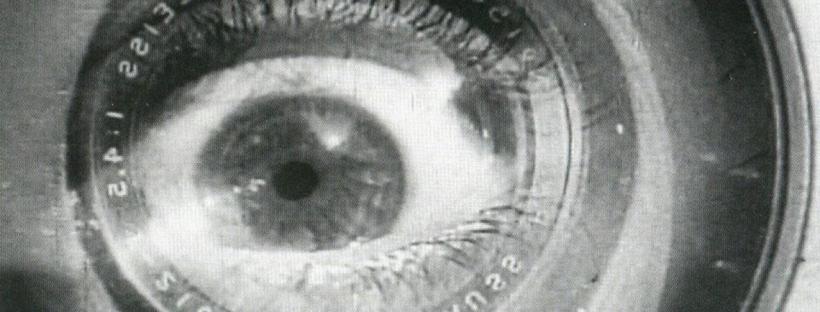

I filmed my cataract operation, so I saw Dr Agarwal cut into my eye and replace my old cataract with a new one. My eye looked like a jellyfish. The new cataract looked like an insect unfurling its wings.

The film adaptation of The Story of Looking will be released in 2021.