In 1571, 38 year-old French Renaissance thinker, lawyer, civil servant and statesman Michel de Montaigne retired from public life, eschewing company and the great outdoors to instead exist alone in a tower: the ‘citadel’ of the Château de Montaigne; the home of his landed gentry family. His best friend, Étienne de La Boétie, had died of plague some seven years earlier: a retreat to the tower was a chance to process this great loss.

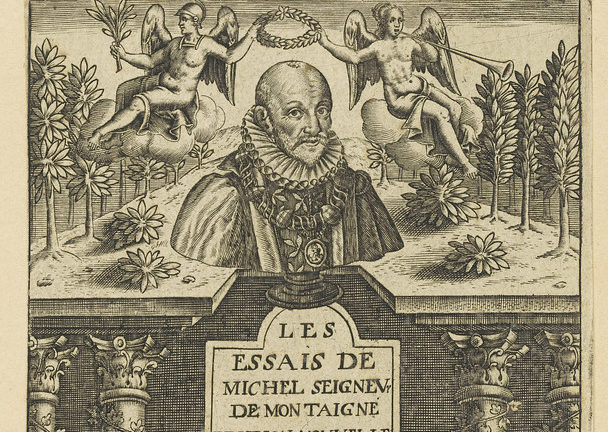

His seclusion was nothing if not productive. In the tower, Montaigne wrote his Essays: three volumes and 107 chapters focused quite unapologetically on Montaigne’s own thoughts and feelings. How lovely, it’s easy to think, for him to have had a castle within which to take refuge from life’s cares and furthermore to write at length about matters close to him. Lucky old Montaigne, a family estate near Bordeaux — all right for some.

On the other hand, seclusion in a tower sounds rather lonely, especially in the light of such agonising personal loss, and set against the wider climate of a raging bubonic plague epidemic. Bordeaux, writes Robert Zaretsky, was, in the late 1500s a hot spot for bacteriological plague. An image persists to this day of an isolated Montaigne scribbling away in his library within the tower, its thick stone walls providing a refuge from the world, his lone figure sitting in a chair, surrounded by a thousand silent tomes, back arched over a parchment, eyes straining to see by candlelight. However, this image never quite reflected reality. Reports of Montaigne’s seclusion were, to all intents and purposes, greatly exaggerated.

In Jane Kramer’s New Yorker article Me, Myself, And I: What made Michel de Montaigne the first modern man? it is accentuated that Montaigne was never really confined to his tower in the twenty-year period in which he wrote Essays, or at least not to the extent that has been carried through in common wisdom in the intervening centuries since the Renaissance statesman lived. It seems Montaigne went “to the best parties in the neighbourhood”, attended “all the important weddings” and corresponded with “beautiful, educated women” who read his drafts. Montaigne also left his castle in 1580, for travelling, and again in 1581 to become the mayor of Bordeaux.

Monastic seclusion? More like fine living… Though this is a serious point. Montaigne’s self imposed seclusion worked because he was able manage his interactions and, by contrast, revel in a self-won solitude. He uses Chapter XXXVIII of Essays to address solitude and discuss the benefits of time spent in one’s own company, a recognition that while he was alone much of the time he had the option of seeing other people and socialising. Though circumstance made his retreat prudent during a time of plague, it was an example of his own free will being exercised, not limited.

The Covid pandemic of 2020 brought with it enforced lockdowns for many hundreds of millions of people around the world: people were advised to self-isolate, to distance themselves, to stay home. Celebrities found to be breaching lockdown regulations were shamed in the press, and rightly so. Faced with months of self-isolation, many people used the time indoors on creative, reflective and productive pursuits: to use a very small example, in May 2020 Oxford University Student Counselling Service advised students to journal their thoughts, while in October, Frieze Art Fair became an online event for the first time. This is in a wider climate of UK schoolchildren both unable to return to school and lacking the technology at home to participate in online learning.

While great efforts have been made by the educational and cultural sectors to encourage people to take up meaningful hobbies and creative pursuits, more needs to be done to alleviate loneliness and the stultifying effects of tedium. An online art fair is certainly a chance for enthusiasts to see new and exciting art (albeit through a screen), but to what extent are participants able to communicate with and learn from each other? Equally, to what extent is journaling actually therapeutic? Yes, Montaigne used his time in his tower library to process his grief through writing Chapter XXVII of his Essays “On Friendship”, but he also had an active and varied social life, both in person and through written correspondence: he was not completely alone.

The UK government has a Local Connections Fund which aims to “help local organisations bring people and communities together as the country recovers from the coronavirus pandemic”, but it remains to be seen how small grants “worth between £300 and £2500” will benefit those most at risk from isolation. The Good Things Foundation, a social change charity based in Sheffield, states that 11.3 million people living in the UK do not have the basic digital skills they need to thrive and connect in today’s world.

That fact speaks volumes. The digital channels so many of us have opened socially and professionally in 2020 may feel like second nature but there is a huge, vulnerable section of society isolated twice: by the physical lockdown and then by the barriers to digital access. However, by addressing this social need for digital connectivity, our cultural institutions have a chance to further their boundaries, engaging new audiences.

I acknowledge that Covid regulations are there for a vitally important purpose, and will adhere to them wholeheartedly, but greater efforts are needed to connect a wider range of people in meaningful online cultural debates, stimulating virtual events and inclusive digital art launches. Then we might really see the productivity of solitude sought by Montaigne and our Covid-stricken cultural institutions.