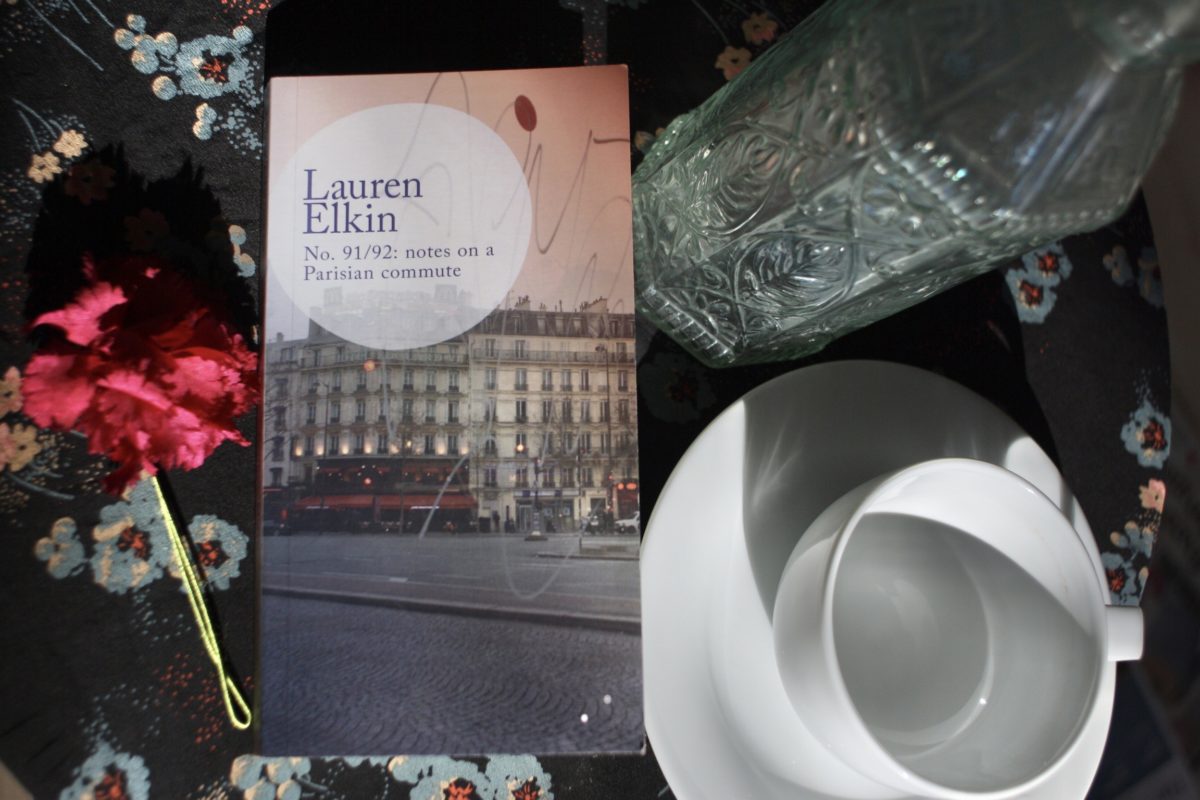

The Parisians on the bus in Franco-American writer Lauren Elkin’s book No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian commute stare at their notifications: they tap and swipe, tap and swipe, their phones appearing “little wells of blue glowing in the thick dark of morning”. As Elkin makes her usual journey through the French capital on two buses one Thursday afternoon, the quatre-vingt-onze followed by the quatre-vingt-douze, she measures this period of her life not in coffee spoons but by what she calls the “Parisian measure of Haussmannian buildings”, one “every couple of minutes”.

Despite its frequent vistas of architectural grandeur, there is the marked tedium of the commute: the squabbling infants, the crawling pace of traffic, the people who won’t give their seats to those more in need. Against this, anecdotes betray Elkin’s fondness for her “anonymous fellow bus-riding Parisians”. Commuters abound, and the sense of curiosity is infectious: “why?”, asks Elkin. “Where are they going? What are these lives that live in such increments, between one stop and another?” Her daily travels, lived between 2014 and 2015, are bejewelled with sartorial appraisals, such as that silently given to a Parisian whose “glittery sandals are awful” but the rest of their outfit is “good”. On another day, a young woman sports fetching mulberry-hued lipstick. Elkin finds herself thinking that the young woman’s hair roots, while box-fresh now, will one day cede to flecks of grey.

Passing thoughts about ageing give way to existential despair. At one point, Elkin finds herself re-evaluating the topic of a talk she was intending to give about Zadie Smith, thinking instead that she ought to “do it on that Thatcher quote, what was it again? Something about being a loser for taking the bus after 30. I’m 36”. On another occasion, she muses on the possibility of a new commute, a commute on the Paris Metro, if she gets “a job at another school, a permanent job” after her child is born. The sadness that follows is documented in fragments; thoughts borne amid the sighs of fellow bus-riding Parisians.

There follows the terror of the Paris attacks of 2015, which François Hollande refers to as an “act of war”. The attacks result in brutal panic attacks, “rational friends” avoiding the metro and the whole of Paris gamely “trying to survive and be happy”. Elkin relates how the attacks have the unanticipated effect of bringing the community together somewhat: “Paris is not a ghost town, despite what they’re saying on the American news”. As the city’s inhabitants continue to duck and weave through the great metropolis, they are undefeated, together.

Impressions of passers-by are interspersed with reflections on the writers Elkin enthuses about in her university teaching job. Readers will enjoy the musings on Georges Perec’s An Atttempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris and how learning to appreciate infra-ordinary might make quotidian life a bit more special. It is “tough” to notice everything in day-to-day life, but it is “freeing”.

Remarkably, the book was written entirely using the Notes app function on an iPhone. At the September launch at the Institut français in London, Elkin spoke of how at the time of writing these notes, she was “en mode flâneuse, qui regardait autour de moi [In wanderer-observer mode, looking all around me]”, as she travelled on buses 91 and 92 over a period of seven months, the journey taking “une petite demi-heure [half an hour]“, from her flat to the American University in Paris. Her note-taking is inspired, in part, by a sign published by RATP advising commuters to be vigilant with their mobile phones: “your telephone is precious. It may be envied”. Elkin elects to use her phone to document the world around her, she deems these methods of doing so to be “exercises not in style but in vigilance”.

Would Elkin, now resident in Liverpool, write in a similar fashion about her journeys on transport through the famous maritime city and home of The Beatles? “No”. She responded at the launch, “I would not wish to seem flippant. […] I have the impression that a lot of the people on the buses locally have very different backgrounds to mine. I think [the task] would be for somebody who comes from Liverpool, or who knows the city incredibly well”.

No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian commute offers absorbing and compelling vignettes: you will look, read it, and look at passing fellow citizens with renewed interest and, if lucky, a touch of Elkin’s unfeigned curiosity for life’s passing moments.

No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian commute is available from LesFugitives, publisher of contemporary French writing in translation.