A few months ago, I wrote about the prevalence of sequels in contemporary cinema. There has been a glut of follow-on movies in 2024, and the reason is straightforward: by making a sequel, you tap into an established audience and proven intellectual property. The public already knows what it can expect, so half of the marketing is already done. It risks creative sterility, but it makes financial viability more likely, and that is the bottom line. It always has been.

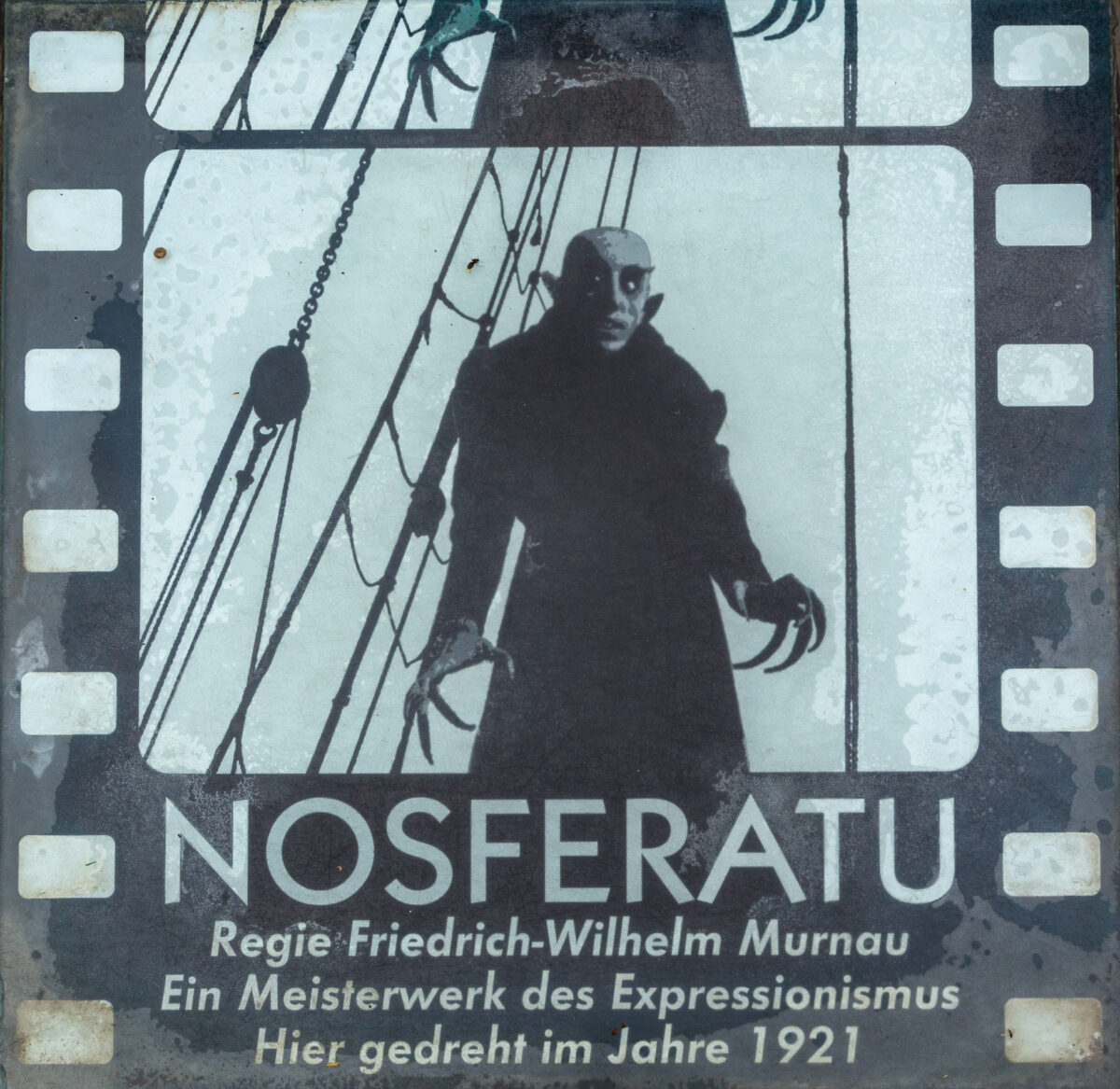

Some of the same logic which drives sequels can be applied to remakes. The framework in established and the storyline known, uncertainty minimised. Sometimes a director can achieve a strange and seemingly contradictory promise of presenting a familiar plot but reimagined or reinterpreted to offer surprise. How could you cover more bases? Last year Disney brought The Little Mermaid back to the screen in a live-action version of the original animated feature, while director Calmatic remade the 1992 Woody Harrelson/Wesley Snipes comedy White Men Can’t Jump. At the end of this year, folklore and mythology devotee Robert Eggers has set his sights higher, and will release a remake of the 1922 German Expressionist masterpiece Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens (“Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror”).

An homage by Eggers to a classic

This is a passion project for Eggers, almost a decade in the making. It was announced in July 2015 by Jeff Robinov’s Studio 8, hard on the heels of Eggers winning the directing award at the Sundance Film Festival for The Witch, his self-penned feature debut. But Eggers was uncomfortable with such an ambitious undertaking being his second film: he said in an interview that “it feels ugly and blasphemous and egomaniacal and disgusting for a filmmaker in my place to do Nosferatu next”. A few months later, Anya Taylor-Joy, who had starred in The Witch, was cast as heroine Ellen Hutter, but, like many films, momentum seemed elusive, and Eggers transferred his energy to The Lighthouse, an atmospheric, black and white psychological thriller which premiered at Cannes in May 2019.

Two years ago Nosferatu regained some pace. Sweden’s Bill Skarsgård was cast in the lead role as Count Orlok, and Lily-Rose Depp replaced Anya Taylor-Joy. Filming began in the Czech Republic in February 2023, and by May Eggers, his cast and crew were done. The film will be released on Christmas Day this year, distributed in the United States by Focus Features and internationally by Universal Pictures. It will be Eggers’s fourth feature.

Nothing in cinema is sacred, we know that. If there had been any doubt, it was swept away by Gus Van Sant’s nearly shot-by-shot remake of Psycho in 1998, a baffling endeavour which neither reinvigorated Hitchcock’s magnetic original despite a respectable cast headed by Vince Vaughn and Anne Heche, nor did much to pay tribute to it, standing alongside as an awkward, full-colour half-sibling. Despite that, remaking Nosferatu is a challenge of monumental proportions, because it is not merely a great and pioneering film—though it is undoubtedly that—but because the original is hedged with dark glamour, myth and a degree of superstition.

The making of a masterpiece

Nosferatu began in part as a cheat. It was an unofficial and unauthorised adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel horror masterpiece Dracula (1897), and although several details were altered to distance it from the source material and the book was acknowledged as the source in the original German intertitles, it was not a watertight legal defence against copyright infringement. Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker’s widow and literary executor, was alerted to the film’s existence by an anonymous letter from Berlin after it opened in March 1922, and was furious. She was struggling financially, so decided to begin legal action against Nosferatu’s producers, Prana Film, demanding not only financial compensation but also the destruction of the negative and all prints of the film. She eventually won, the German court ruling in July 1925 that the reels be surrendered to her but, thankfully, some prints which had been sent abroad survived.

There was another, darker, eerier side to the film. Prana Film had been founded in 1921 by producer Enrico Dieckmann and artist and architect Albin Grau. The latter, in his mid-30s, was a keen occultist who had chosen the enterprise’s name after a Theosophical magazine and hoped to make films on occult and supernatural themes. Grau claimed that he had been inspired to plan a vampire story by an incident in 1916 when he had encountered a Serbian farmer who told him his father was a vampire and one of the undead. It was under his influence that Nosferatu featured strong occult themes, its set bedecked with Enochian symbols.

For the screenplay, Dieckmann and Grau turned to 41-year-old Austrian actor, director and writer Henrik Galeen, who had six features to his credit going back to 1915’s Decla-Film horror The Golem (in which he had also played a starring role). Galeen was an admirer of Hanns Heinz Ewers, a well known author, poet and philosopher from Düsseldorf who had spent the First World War in the United States as a vocal advocate of imperial Germany’s cause. Many of Ewers’s works dealt with occult, mythological and folkloric subjects, and he lectured extensively on “the Religion of Satan”. He was also a friend and correspondent, perhaps inevitably, of Aleister Crowley.

Galeen’s text was steeped in myth and dark romanticism. To Stoker’s original story he added the notion of the vampire bringing with him plague-carrying rats, nodding to folk memories of mediaeval Europe and the continent-wide catastrophe of the Black Death, which had killed as much as half the population. Stylistically, the screenplay was rhythmic and metrical, an aspect of Galeen’s Expressionism; the critic Lotte Eisner, in her Murnau. Der Klassiker des deutschen Films, one of the seminal texts on German Expressionism, would later describe it as “voll Poesie, voll Rhythmus” (“full of poetry, full of rhythm”).

And of course there was the director. F.W. Murnau was a towering man of 33, who had spent the latter years of the First World War in the Imperial German Air Service and been involved in eight severe crashes without serious injury. He was born Friedrich Wilhelme Plumpe but seems to have taken his pseudonym from the market town of Murnau am Staffelsee in Upper Bavaria. At least six-feet-four, though some sources placed him closer to seven feet in height, he was a cinema obsessive, and some contemporaries found him cold and imperious. His friend and lover, Hans Ehrenbaum-Degele, had been killed on the Eastern Front in 1915, and it had caused Murnau to become more withdrawn and detached, as well as more immersed than ever in film.

Shortly after returning to Germany at the end of the War, he started a film studio with actor Conrad Veidt, and his early films—many now lost except for some fragments—featured many dark, supernatural and paranormal themes: Satanas (“Satan”), Der Bucklige und die Tänzerin (“The Hunchback and the Dancer”) and Der Januskopf (“The Janus Head”), an adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, all made in 1920, Schloß Vogelöd (“The Haunted Castle”) of 1921 and Der Brennende Acker (“The Burning Soil”) of 1922.

Murnau was hardly alone in his exploration and the dark and eerie. This was the era of the Expressionist movement, which turned away from the priority of realism to explore inner emotions and indulged in bold experiments with plots, sets and cinematography. In the few years between the end of the War and the filming of Nosferatu, the German film industry, financially straitened but creatively booming, would produce strange, unsettling and pioneering masterpieces like Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari (“The Cabinet of Dr Caligari”), directed by Robert Wiene, Karlheinz Martin’s Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morn to Midnight”) and one of Fritz Lang’s earlier directorial works Der Müde Tod (“Destiny”).

Creating a horror archetype

The final piece in this weird jigsaw was the casting of Nosferatu’s lead character, the vampire Count Orlok. Murnau’s collaborator Conrad Veidt was approached for the role but had to refuse for scheduling reasons (he appeared in 16 films in 1920 and 11 in 1921), and after a lengthy search the producers chose a little-known 41-year-old actor called Max Schreck. A Berliner by birth and upbringing, he had been fascinated by the theatre since childhood and had trained at the Staatstheater in the early years of the century before joining Max Reinhardt’s company.

From 1919 to 1922, Schreck worked at the Munich Kammerspiele under director and manager Otto Falckenberg. As well as his stage roles, he made his first steps into cinema, with a début in Ludwig Berger’s 1920 Der Richter von Zalamea (“The Mayor of Zalamea”) and a part in Berger’s popular Der Roman der Christine von Herre (“The Story of Christine von Herre”) of the following year. Fellow performers found Schreck an oddity; like Murnau, he was solitary and distant, and liked to walk alone in forests, retreating to an interior mental and emotional world.

What would seal Nosferatu’s place in the cinema pantheon was Schreck’s physicality. He was renowned for his ability to play grotesques, and as Count Orlok he gave an iconic performance which resonates and chills more than a century later. Already tall and lean at six-feet-three, with deep-set eyes and a prominent nose, Schreck wore a bald cap, jutting ears and long, talon-like fingers to portray the vampire. He wore a close-fitting double-breasted coat which emphasised his thin silhouette and carried himself with an unsettling stillness, an inhuman and ineffably sinister figure. So familiar now is his hunched posture, shoulders high and spindly fingers extended menacingly, that you can buy a lamp which casts Orlok’s shadow on the wall.

The legend of Nosferatu

Fame breeds fame, or perhaps we should call it infamy. There is strangeness enough about Nosferatu but the film’s legend had spawned its own lore. When it was first released, there were rumours in the industry that “Max Schreck” did not exist at all—perhaps given credence by the fact that in German Schreck means “terror” or “fear”—but was a pseudonym being used by another actor, Alfred Abel. He and Schreck were very close in age, perhaps bore a passing resemblance to one another if Count Orlok’s make-up and costume were taken into account, and both had worked under Max Reinhardt. Abel had also acted in two of Murnau’s earlier films, Phantom and Der Brennende Acker.

In 2000, director E. Elias Merhige took this canard further with his quirky and atmospheric Shadow of the Vampire. Starring John Malkovich as F.W. Murnau, the film posits that Schreck (played by Willem Dafoe) was not only not a little-known theatre performer but was, in fact, a genuine vampire. The screenplay by Steven Katz depicts the making of Nosferatu, and has Murnau keep Schreck separated from the rest of the cast and crew except when actually filming. Another actor, Gustav von Wangenheim (Eddie Izzard), who plays the protagonist Thomas Hutter, explains that Schreck wishes to remain wholly in character and will only appear in costume and make-up.

It is a surprisingly effective and unsettling picture, and the performances from Malkovich, Dafoe and Izzard, as well as Cary Elwes and cinematographer Fritz Arno Wagner and Udo Kier as Albin Grau, are outstanding. What is most telling, however, and which illustrates the power of Nosferatu and its cultural impact, is that the apparently far-fetched premise is very easy to accept and absorb. Well, you find yourself thinking, what if Schreck really was something other than an obscure German actor? What if there was something more sinister about him?

Another ripple of unease came in 2015, when Murnau’s grave in Stahnsdorf, a few miles east of Potsdam, was broken into and the director’s skull was stolen. Wax residue was found near the site, suggesting that candles may have been lit for some kind of occult ceremony, and the cemetery administrators revealed that it was not the first time Murnau’s burial site had been disturbed. It might mischievously be noted that in German and western Slavic traditions, vampires could be killed by decapitation and the burial of the head away from the body. Murnau’s skull has to date never been found.

Robert Eggers is not the first director to reinterpret Nosferatu. The iconoclastic and innovative German director Werner Herzog adapted the Dracula story in 1979 and titled his film Nosferatu the Vampyre; the setting is cribbed from Murnau’s film and Klaus Kinski as Count Dracula is made to resemble exactly Schreck’s Count Orlok. Herzog once said “Murnau, I consider to be the greatest German director, and Nosferatu the greatest German film”, and the result was considered by critics to be not only a reverent homage to the original picture but also an atmospheric and impressive film in its own right.

In 2014, David Lee Fisher launched a campaign on crowdfunding platform Kickstarter to raise money to make a new interpretation of Nosferatu. He raised $60,000 in two months, and 18 months later announced the casting of actor, mime artist and contortionist Doug Jones as Count Orlok. Jones had played the sleepwalking minion Cesare in Fisher’s 2005 remake of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. The film has not yet found a distributor, but had a premiere at the Emagine Theatre in Novi, Michigan, in December 2023 followed by a limited release.

Eggers has chosen a formidable cultural artefact to recreate. Nosferatu is a challenging summit to attempt on several counts: it is a pioneering and iconic example of German Expressionism, highly stylised and instantly familiar; in Count Orlok it has one of the most recognisable and imitated characters in the history of horror (surely the only cinematic figure to be portrayed by both Klaus Kinski and The Fast Show’s Paul Whitehouse); and the original film, more than a century old, has its own weighty accumulation of legend about it and its production.

A remake now cannot have the visceral, historic impact of Murnau’s original production. In 2019, even Eggers himself seemed uncertain of his undertaking. “I don’t know,” he admitted to entertainment website Den of Geek, “maybe Nosferatu doesn’t need to be made again, even though I’ve spent so much time on that.”

On the other hand, his previous work, especially The Witch and The Lighthouse, shows a meticulous and affecting Gothic horror sensibility, and his reverence for the source material is profound. Bill Skarsgård as Count Orlok could be an inspired casting decision, while Nicholas Hoult has the confident innocence for a convincing Thomas Hutter. Although Lily-Rose Depp, cast as Ellen Hutter, carries the “nepo baby” burden of famous parents, she received positive reviews for her performances in My Last Lullaby and The King. Willem Dafoe’s appearance as Prof Albin Eberhart von Franz is a generous nod to Shadow of a Vampire.

We should, like Professor van Helsing in Stoker’s novel, try to keep an open mind. Perhaps Eggars will remember the words of Hutter’s employer, the estate agent Herr Knock: “It will cost you some effort… a little sweat and… perhaps… a little blood.” It seems an appropriate price for the tale of a vampire.

(Note: F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens entered the public domain in 2019. The film can be seen in its entirety here.)