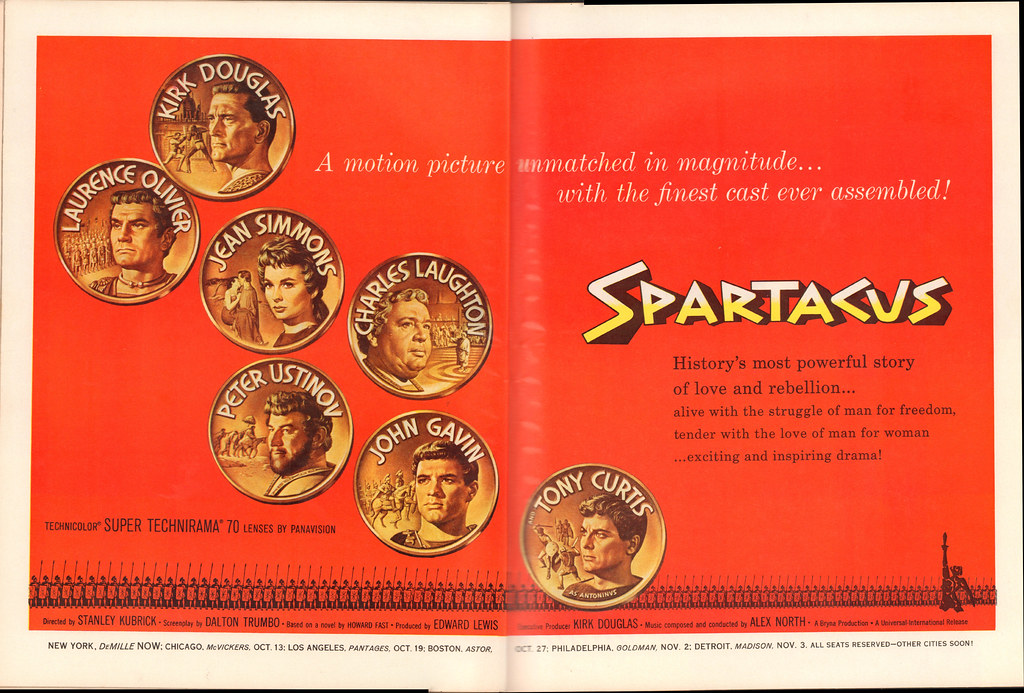

We’ve all seen Spartacus. It’s a classic of the sword-and-sandals genre, as well as part of the slender canon of films directed by Stanley Kubrick—only 13 feature films and three short documentaries over the course of his career. The story of a slave rebellion in ancient Rome which became the Third Servile War, it has enlivened many a bank holiday afternoon, and features a formidable cast, from its leading men, Kirk Douglas and Laurence Olivier, to the character studies provided by English greats Charles Laughton and Peter Ustinov.

Spartacus was a box office hit when it was released in 1960. It was the highest-grossing film of that year, bringing in $17 million, and Variety noted wryly that “Kubrick has out-DeMilled the old master”. Critics were divided, some savaging Douglas’s stiff performance as the eponymous slave, while Hedda Hopper, one of the titans of the review pages, was blunt: “The story was sold to Universal from a book written by a commie and the screen script was written by a commie, so don’t go to see it.” But people did.

In 1991, the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles, having recently staged a tribute to Kirk Douglas, asked Universal Pictures for a print of Spartacus. The original negatives were in a poor state, the colours having faded badly, while Kubrick’s own print of the film, held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, was considered a priceless archival source and could not be released. A restoration project followed, which gained the backing of Steven Spielberg, using the original studio black-and-white separation prints.

Stanley Kubrick himself, although he had disowned the original film, gave his blessing to the restoration and provided guidance by telephone and fax from London. The new print allowed the restorers to reinsert scenes which had been deleted from the original cinematic release, mostly because they were considered too violent for 1960’s audience (an opinion confirmed in test screenings).

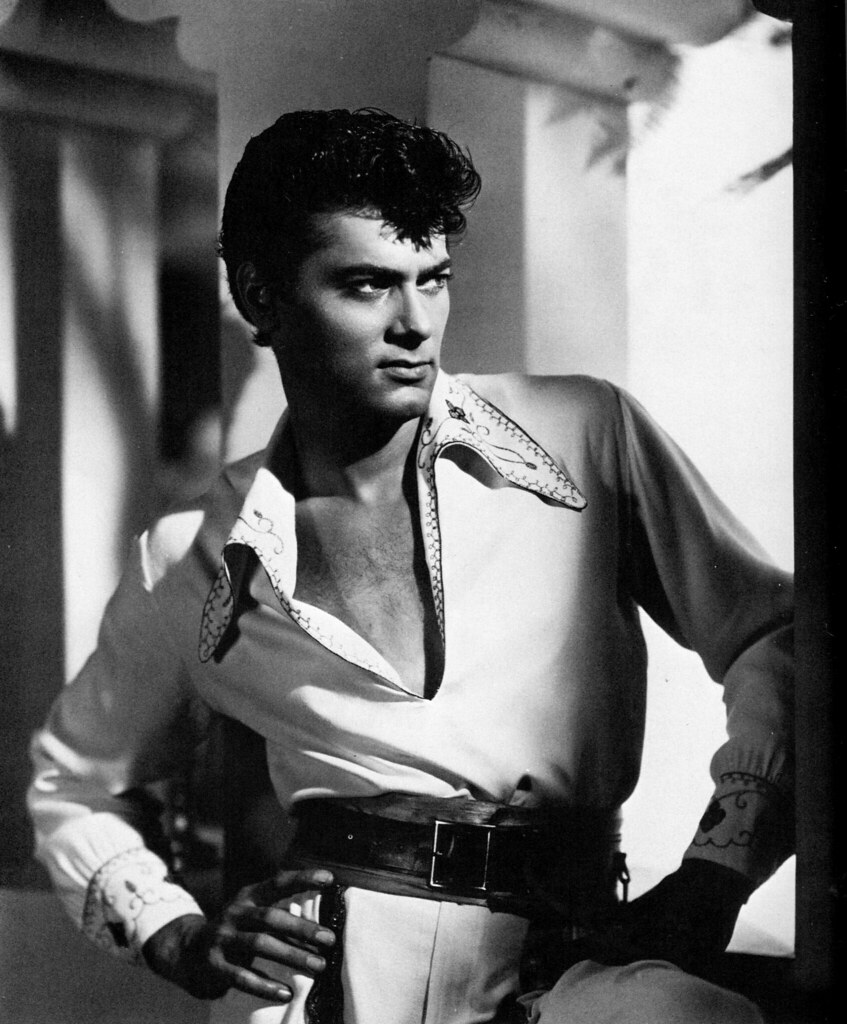

One restored scene is of particular interest, and was not omitted because of its violence but because of its ambivalent attitude towards sexuality. Marcus Licinius Crassus, a rich and aristocratic Roman general played with archly feline campness by Laurence Olivier, is bathing, attended by his slave, Antoninus (then-Hollywood heartthrob Tony Curtis). Embarking on an extended culinary metaphor, Crassus lays out a subtext which, even for the 1960s, was not particularly ‘sub’; it would have taken a naïf soul indeed not to realise that the general is trying to seduce the slave.

The dialogue is, to the modern ear, thunderingly suggestive, and is worth quoting at length.

Crassus: Do you eat oysters?

Antoninus: When I have them, master.

Crassus: Do you eat snails?

Antoninus: No, master.

Crassus: Do you consider the eating of oysters to be moral and the eating of snails to be immoral?

Antoninus: No, master.

Crassus: Of course not. It is all a matter of taste, isn’t it?

Antoninus: Yes, master.

Crassus: And taste is not the same as appetite, and therefore not a question of morals.

Antoninus: It could be argued so, master.

Crassus: My robe, Antoninus. My taste includes both snails and oysters.

What had been, in 1960, a brave attempt by scriptwriter Dalton Trumbo to reflect the nuances of Roman (and Greek) attitudes to same-sex love and intimacy is now a straightforward depiction of homosexuality. But Trumbo, who had been blacklisted for refusing to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee in their search for communists in the movie business in 1947, had been too bold. The National Legion of Decency—a disheartening name if ever there was one; it was a front for the Catholic Church and most local chapters were run by parish priests—had vetoed the scene, and it fluttered to the cutting room floor.

Restoring the scene presented some challenges. The main one was vocal: the soundtrack had been lost and the frames were silent. Revoicing Antoninus was easy enough. Tony Curtis, though 66 by this stage, re-recorded his racy lines. But Lord Olivier (as he had become) had died in 1989. A quirkily ingenious solution was found: Olivier’s widow, Dame Joan Plowright, suggested that Anthony Hopkins, a gifted impersonator among his other talents (he would go on to mimic fellow Port Talbot native Richard Burton in advertisements for British Gas), stand in for her late husband. Hopkins was particularly fitting as he had been a disciple of Olivier during the latter’s stint as artistic director at the National Theatre.

So the four-minute scene was brought back to life and unleashed on a new, and more broad-minded, audience, three decades on. Does it add much to the film? Arguably not: the theme of sexual ambivalence is not explored further and the bathing scene remains a rather arch little oddity, occasion for a titter but little else. It is a technical curiosity, however, and very skilfully done. If you watch it now, it is very easy to forget that it is not Olivier’s voice at all; remarkable since the great thespian had extremely distinctive tones which were a gift to impressionists, and Olivier himself verged on self-parody at times.

But ‘oysters vs snails’ stands out as a hint of something much more complicated—dare one say even more interesting?—than the noble resistance and tragic fate of Spartacus and his fellow slaves. It is as if someone has drawn back a veil to reveal a quite different film: a film, perhaps, that Kubrick ought to have made…