Can art really be enjoyed remotely? Can it be restored remotely? To answer these questions, look at the Rijksmuseum’s new website: the reconstructed version of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch is, as of today, displayed on the site, allowing virtual visitors to explore discoveries made in the course of the iconic artwork’s restoration and expansion during ‘Operation Night Watch’. A video revealing how the reconstruction came about provides ripe learning opportunities for the art-curious and can be found here.

There’s a great sense of excitement and mystery about the restoration: it’s a century-spanning tale of missing canvas pieces; of artistic intent; of the evolution of art restoration processes and the skills behind them.

Each generation has used the tools available to it to attempt to reconstruct the painting. Now we are doing the same, using the most advanced techniques currently available.

Pieter Roelofs, Head of Paintings and Sculptures, Rijksmuseum

View of Kloveniersdoelen in Amsterdam, Zacharias Webber (II), 1665, Rijksmuseum collectio

From archival research to artificial intelligence

The Night Watch was originally painted for the Great Hall (Groote Sael) of the Kloveniersdoelen, the headquarters of several companies of the city’s militia. The painting formed part of an ensemble together with six other large group portraits, all painted between 1640 and 1645, but less than forty years later the building had lost its original purpose and a new home was needed: in 1682 the Amsterdam Burgomasters decided to relocate the paintings to the newly-built Town Hall (the present-day Royal Palace on Dam Square).

Here they encountered budget issues: no funds to finish the intended decoration scheme. Time to move again. The paintings were moved, over the course of ten years, and treated in their transient homes, but the archival team note that it wasn’t standard practice in the seventeenth century to “specify on which paintings work was being done […] we cannot know for certain if Jan Rosa [a distiller, painter and appraiser whose name often shows up in the city archives in connection to the repair of paintings] also treated The Night Watch, let alone what he did exactly”.

Eighteenth century records would also prove hard to come by: there is mention of an order to clean “the large painting by Rembrandt hanging in the room of the Kloveniersdoelen” but records are lacking as to how or by whom this would have been carried out. There is, however, the work of painter, connoisseur and restorer Jan van Dijk (c. 1690–1769), who was keeper of the Town Hall between 1746 and 1766 and who in 1751 and 1752 treated all paintings in the Small War Council Room, including The Night Watch.

The restoration team behind Operation Night Watch say that in 1756 van Dijk published a small volume called Kunst en Historiekundige Beschryving en Aanmerkingen over alle de Schilderyen op het Stadhuis te Amsterdam (Art and Historical Description and Comments about all the Paintings in the City Hall in Amsterdam), in which he lamented the fact that the painting was cut down in size to fit between the two doors of the small war council room. On the left side, two whole figures had been removed, and on the right side part of the drummer.

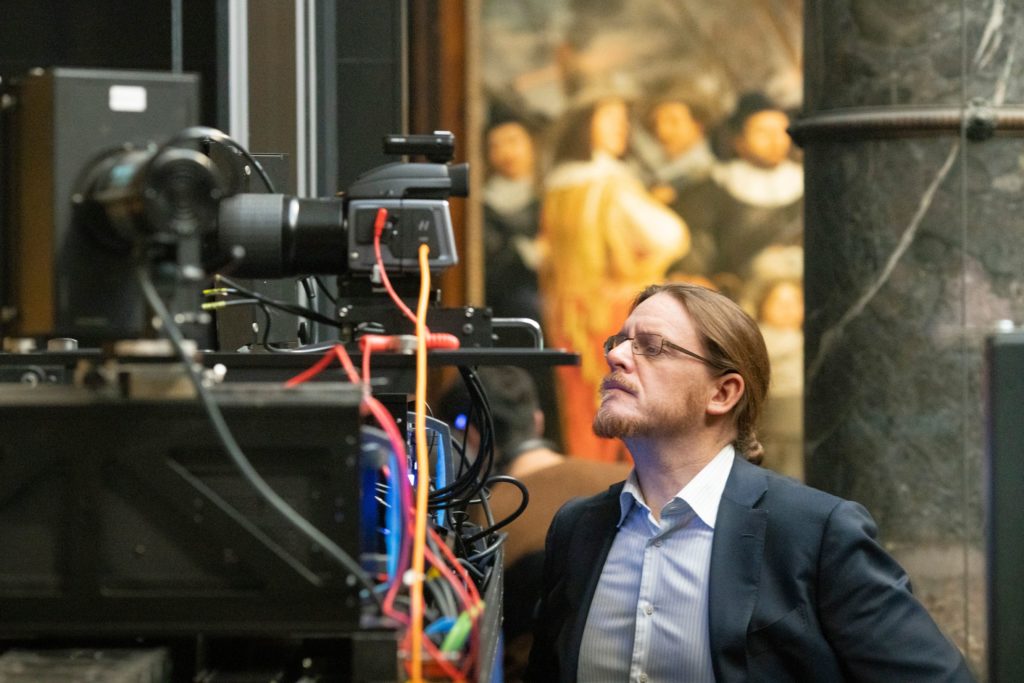

From these archival findings and losses via nineteenth century arguments as to whether the painting had been cut or not, The Night Watch progressed to the care of twenty-first century scientists, who used the neural network of artificial intelligence to tell the computer involved in the restoration to recognise what colours Rembrandt used, and what brush marks he had made. The video explains the process and how, with great care and great attention, the Netherlands’ most cherished artwork has used the most modern of methods to return to its former glories.

This project testifies to the key importance of science and modern techniques in the research being conducted into The Night Watch. It is thanks to artificial intelligence that we can so closely simulate the original painting and the impression it would have made.

Robert Erdmann, Senior Scientist, Rijksmuseum

IMAGE TOP: Rijksmuseum/Reinier Gerritsen