It was Brazilian legend Pelé whose playing style popularised the description of football as o jogo bonito, “the beautiful game”. The phrase had been reported before, by such unlikely sources as Stuart Hall and HE Bates, but it was that cusp of the 1960s and 1970s, when football was being transformed from a monochrome blur on a screen to the wild, over-vivid technicolour of Mexico ’70, that saw the game transformed in the public consciousness. It was still a sport with mass appeal and working-class roots, but now it had its own aesthetic, its own dynamism, almost its own philosophy.

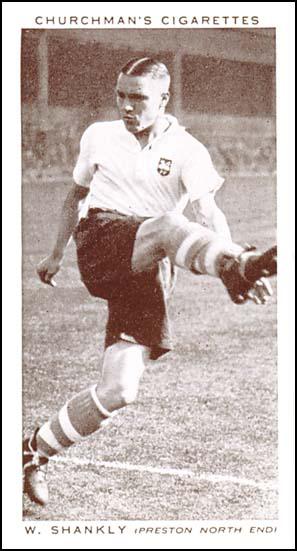

Today, of course, it is all-conquering. It may be a half-century since Bill Shankly observed dryly that “Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you, it’s much more serious than that.” But he was right. Football (or soccer, in North America) is easily the most popular sport in the world, with an estimated 3.5 billion fans across the globe. The big names in terms of players, managers and clubs are international brands and huge income-generators. Neymar Jr, Paris Saint-Germain’s Brazilian superstar, is estimated to be worth $185 million; Spanish legends Real Madrid are worth considerably north of $4 billion.

What is it, though, about football which appeals so powerfully to the hearts and minds of people across the world? What’s the special resonance it has? How has it come to have an attraction which is not only almost universal, but also in many cases very profound?

Football, of course, comes in many forms: from the electrified crowds rapt by Champions’ League final, to a non-league Sunday afternoon fixture in front of a hundred spectators, most of whom know the players personally. That spectrum is at once huge—from the elite athletes of the Premier League to part-timers who feel their lungs burning by full-time—and at the same time very narrow: whatever you are going to watch, you will find a game of the same sport, played by the same number of people, of a standard far beyond anything you could achieve. So it’s aspirational and idealised. It’s (at least) the next level.

It is also an easy sport to understand. Two teams, two goals, one ball; the objective simple, score more often than your opponents in two periods of 45 minutes. A child could understand it—children do—and, more importantly, a passing observer can pick up the rudiments in seconds, without any prior knowledge or language requirement.

Yet, in its simplicity lies its very richness and drama. The players are at once superman and everyman, doing something we have all done but at a level which we can sometimes barely comprehend. They may be earning thousands of dollars a second, but they are playing on a field, with a ball not utterly unlike that which friends would pass back and forth in the park. But focus the eyes of millions, or billions on to one stadium, one pitch, no matter how grand and well-appointed, and it becomes a cockpit, a theatre for a transcendent experience which is so much more than a simple game. Like all good sports, football wears its history heavily: a true fan will smile or nod or grow misty-eyed at memories of Gazza’s tears at the Stade delle Alpi in 1990, or Maradona’s ‘Hand of God’, or the Busby Babes and their grim end on the slushy tarmac of Munich in 1958.

To be an avid fan is to plug into this tightly woven tapestry, the threads of which were first taken up more than 150 years ago. Narrative snakes through it inextricably, and each game is a story in microcosm. It has each of the five components of any narrative: characters, setting, plot, conflict and resolution. Each is simple and easily sketched. That’s why football speaks to so many of us on an elemental level. It is the story of everything, played out in 90 minutes with the drama of a battle but not of the jeopardy.

It’s not just a football match, then. Shankly was right. It’s much more serious than that.

(This article was first published on Behind the Spine.)