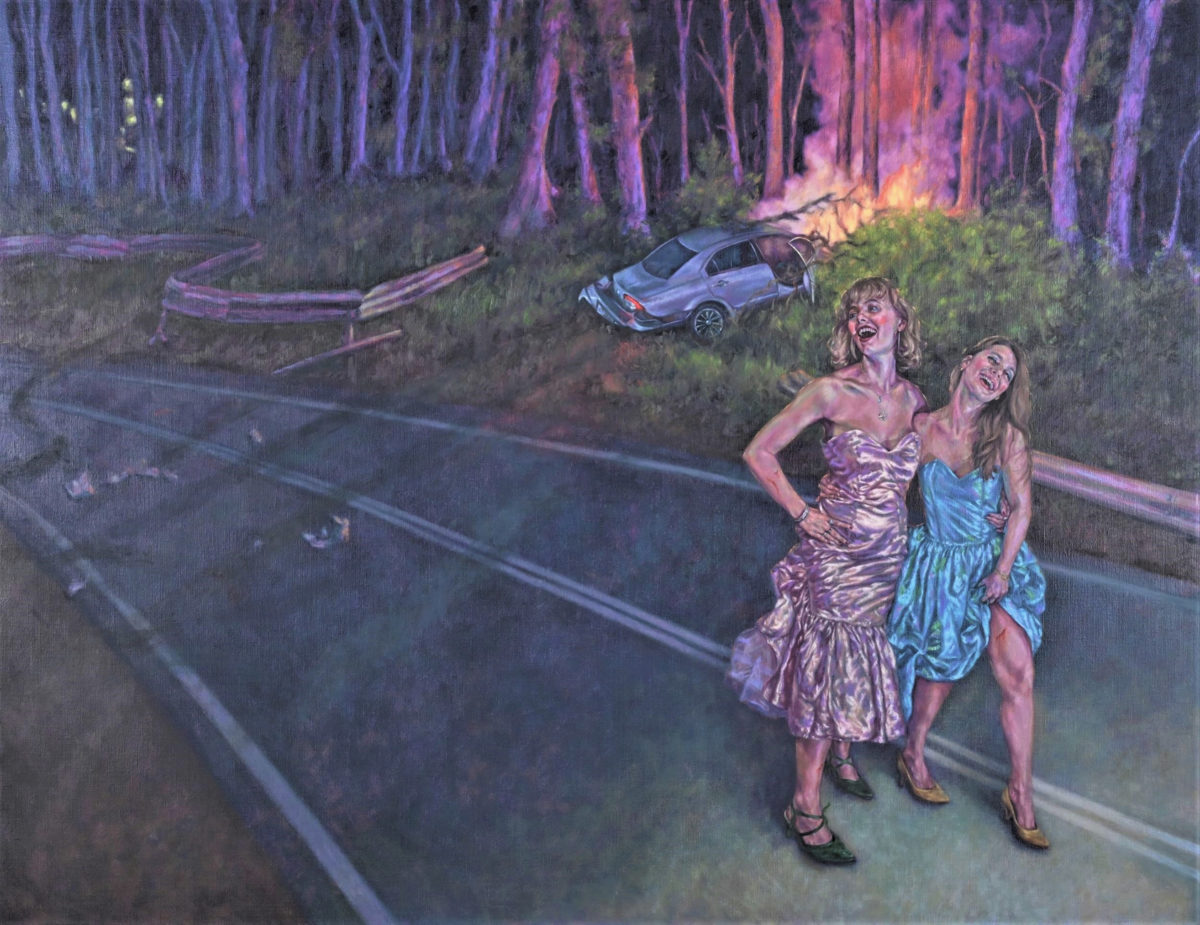

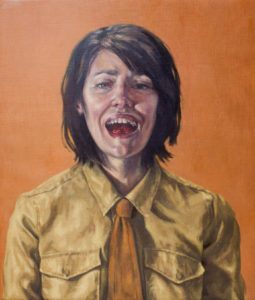

Your forthcoming show – Crime Spree – features subjects really enjoying themselves: laughing joyously and un-selfconsciously while going on the rampage. What inspired this theme?

I’m always thinking about where and how women take up space and disrupt politeness, how they circumvent the impulse toward self-control and containment. There’s an element of violence and threat embedded within a lot of the Laughing works. Mostly the women have done something, or are doing something, catastrophic. Initially, they were doing it purposefully to free themselves from traps, that was my guiding principle, but, increasingly, I have started to think about threat and danger and how women might retaliate. Women are not generally considered a threat, quite the opposite. Largely women go about the world observing the potential of threat and danger, are self-conscious and monitor their behaviour, because they are nervous in the world. It’s interesting to think about examples when women didn’t do that so I’ve been looking into vintage and historical gang culture, Victorian girl gangs, pipe-smoking women from the 40s, Teddy Girls…instances of women getting together in a pack and having an edge of threat and danger about them.

I’ve also been thinking a lot lately about historical examples of individual women engaging in violent acts, murderesses, reactionaries, in relation to my ongoing concerns about the particular prohibitions which are placed on women within society. Plenty has been written and said about this, but it is always interesting to me, the particular kind of opprobrium placed on women who are violent, women who misbehave.

And so I pose my laughing women this scenario: what if there were no guilt, no shame?

I continue to find their response exhilarating.

The seed of Crime Spree was sewn when I saw Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as St Catherine of Alexandria (1615-17), recently acquired by the National Gallery, London. I saw the painting at the library in Walthamstow when it was touring, and I was agog. I knew and loved her work but that particular painting had incredible presence, it just captivated me. It made me think about historical depictions of women, and the kinds of imagery which has been regularly revisited: the female saint, brandishing, bearing, grasping the means of their martyrdom, in particular. They don’t always look triumphant. In fact, they can look quite the opposite: broken, or beatific and soft, which really belies the violence of it all. Simultaneously, you’re being asked to contemplate violence visited upon the physical body in order to release the transcendent soul, and yet somehow these women are supposed to look radiant and beatific despite it all. Artemisia’s painting is so rare in that, yes, it is doing what those paintings do, there is St Catherine, her self-portrait of course, with the wheel, but this is not a woman who has been subjected to violence. I mean, it’s inevitable when you look at Artemisia’s work that you overlay on to it everything you know about her autobiography, but there is a palpable sense that she’s someone who would not allow anyone to subject her to anything, and if that happened, she would avenge herself. It’s such a powerful painting.

Previously you’ve referred to writers such as Hélène Cixous, and have mentioned her piece ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’: when Cixous writes that ‘Our glances and smiles are spent; laughs exude from all our mouths […] we never hold back our thoughts, our signs, our writing, and we’re not afraid of lacking’, is this the sort of sentiment these paintings could be said to contain?

Yes absolutely and isn’t that a beautiful passage? I’ve spoken about how her writing sparked a flame not yet extinguished. I could also mention Marina Warner, the great author and cultural historian and her book, No Go the Bogeyman, which I read when it came out. I’ve no doubt that the section on making mock to free oneself from the fear of dangers real and imaginary lay dormant in me for many years biding its time to inspire images. In it she quotes Freud:

“Humour is clearly one of the chief and most successful ways in which popular culture resists fear. Freud distinguished jokes from humour, commenting ‘Humour is not resigned; it is rebellious. It signifies not only the triumph of the ego, but also of the pleasure principle, which is able to assert itself against the unkindness of real circumstances.”

What artist should everyone know about, but not enough people do?

I often encourage people to look at the work of “Outsider” artists, Art Brut to use another term. There’s often a false hierarchy between artists who are schooled and those who are untrained and often worked in isolation. I’m conscious of how romantic this might sound, but I do feel that with some Outsider artists there is pronounced impression in their work that they were not aware of confines, rules and expectations, that their work was unfettered and ran wild.

Choosing only one is tough but I’ll suggest Lee Godie.

What’s your preferred method of painting – do you work from life?

I really don’t have a preferred methodology and my process evolves over time. My guiding principle is that I must manifest the paintings in my mind by whatever means necessary. Sometimes that means painting from life, it can involve film and photography, memory and imagination. I’ll do whatever the painting requires.

Will we ever escape The Gaze?

No I don’t think so because for many there is no will to extinguish it or even to acknowledge that it persists, it titillates and pleases and will continue to do so. I’ve sometimes thought that one of my jobs as an artist is to identify what for me constitutes a female gaze, while recognising that none of us operate in isolation from all that we have seen, both the nourishing and the noxious, nor can we render ourselves immune.

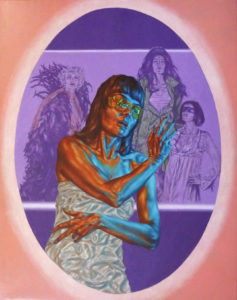

A few years ago I painted a series of works attempting to wrestle with this – my THREESOME paintings in which I tried to employ strategies of resistance to the tired tropes of female representation. The flesh tones of my heroic protagonists were been denatured by a saturation of neon colour, their stylised gestures all uncannily performative, frozen in a gestural polari. Each was flanked by a triumvirate of characters from a very specific history of queer cinema, that of the lesbian as seen by male directors. The actresses who played these roles have been replaced by mannequins who are mere approximations of the original women. I was asking questions about authenticity and spectatorship which I’ll no doubt continue to return to in future work.

Which of your paintings would you say best evokes what you want to say?

That’s an almost impossible question to answer because one’s relationship to the work evolves….plus there’s always an overburdening hope for the next picture to be made. Having said that I immediately knew which one I would choose. Laughing With My Mouth Full.

Roxana Halls’ show Crime Spree runs from 4th September to 2nd October 2021

at Reuben Colley Fine Art Gallery (RCFA), Birmingham. IMAGE TOP: Laughing While Crashing © Roxana Halls (detail), collection of Luke Jennings, author of the Killing Eve novels.