When Garth Hudson died on 21 January, at the venerable age of 87, there was relatively little fanfare in the mainstream media. The loss of a multi-instrumentalist from Windsor, Ontario, whose last live and studio recordings had been in 2013 was not obvious headline fodder. Something profound had indeed happened, however, because Garth Hudson was the last surviving member of The Band.

It started in Arkansas

In 1957, a young Arkansas-born singer, Ronny Hawkins, newly discharged from the United States Army, formed a band called The Hawks in Helena, Arkansas; his bandmates were session guitarist Jimmy Ray “Luke” Paulman, Paulman’s brother George playing a stand-up bass, and his cousin Willard “Pop” Jones on piano. They quickly recruited a high-school student from nearby Turkey Scratch, Levon Helm, as their drummer, and when Helm graduated the following year, the Hawks travelled north to Toronto. The band’s ostentatious rockabilly style, Hawkins resplendent in a pompadour, tight trousers and pointed shoes, was popular in Canada, and their first tour (initially as the Ron Hawkins Quartet) lasted three months.

The association with Canada would be of seismic importance. George Paulman, distracted by drink and drugs and allegedly deemed too “rural” for sophisticated Torontans, was quickly ejected from the line-up, and gradually Hawkins attracted a group of Canadian musicians: guitarist Robbie Robertson, rhythm guitarist Rick Danko, singer and pianist Richard Manuel and, in December 1961, Garth Hudson.

Hudson was 24 years old, a versatile musician who could play the piano, organ, accordion and saxophone and had studied music for a year at the University of Western Ontario. Hawkins was two years his senior, but Helm was only 21, while Robertson, Danko and Manuel were all 18. He had initially declined an invitation to join the band, but eventually relented on two conditions: that Hawkins buy him a sophisticated Lowrey electronic organ, and that the other members of the band pay him an additional $10 a week in return for music lessons.

Enter Bob Dylan

In 1963, the four Canadians and Helm, the Arkansan, parted company with Hawkins due to musical and financial disagreements and spent their time touring, playing in bars and clubs, usually as Levon and the Hawks. In August 1965, they were introduced to Bob Dylan when he came to see them play Le Coq d’Or Tavern in Toronto; he had been encouraged by his manager’s secretary, Mary Martin, a friend of theirs from Toronto who told Dylan, “You gotta see these guys”.

It was only weeks after his controversial performance at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island, where he had played with electric instruments for the first time. History records that the traditionalist folk music lovers of Newport recoiled in horror at Dylan’s “betrayal”. The truth is more complex: having played three acoustic songs at a workshop on the Saturday, Dylan had been irritated by what he regarded as condescending remarks made by festival organiser Alan Lomax when introducing the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and had decided to perform a fully electric set on the Sunday. “Well,” he said to one of his roadies, “fuck them if they think they can keep electricity out of here, I’ll do it.”

He played three songs, Maggie’s Farm, Like a Rolling Stone and Phantom Engineer, and, while some audience members were unimpressed, he was not universally booed. Returning to the stage, he performed Mr Tambourine Man and It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue on an acoustic guitar, and was applauded and cheered. Nevertheless, he would not return to the festival for 37 years.

Dylan was about to begin a six-month tour of the United States and Canada, and initially hired Helm and Robertson to join his backing band. After only two concerts, however, they felt the pull of loyalty and told Dylan they would only continue if he hired Hudson, Danko and Manuel too. He agreed, and from September 1965 to May 1966, they toured as Bob Dylan and the Band. There were also attempted studio recording sessions, with disappointing and scanty results. Robertson and Danko contributed to Dylan’s next album, Blonde on Blonde, released in June 1966 and now regarded as one of the greatest albums of all time.

The following month, however, Dylan, exhausted and over-reliant on amphetamines, was injured in a motorcycle accident near his home in Woodstock, New York. The circumstances of the crash are still mysterious: no ambulance was called and he did not seek hospital treatment. However, he retreated into seclusion, saying later “I had been in a motorcycle accident and I’d been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.”

The declaration of independence

Hudson and the others returned to touring, occasionally backing other artists including, fleetingly and improbably, strange semi-novelty act and ukulele player Tiny Tim. In February 1967, Dylan was ready to work again and invited the quintet to Woodstock; Hudson, Danko and Manuel rented a large pink house in West Saugerties which they dubbed “Big Pink”. Joined by Robertson and, eventually, Helm, they made a series of recordings with Dylan which would only emerge in 1975 as The Basement Tapes. But something else was happening.

By October, they had finished their work with Dylan, and, still living at Big Pink, began to write some of their own songs. Albert Grossman, the manager they shared with Dylan, approached Capitol Records and they were signed initially as the Crackers. Joined by talented young producer John Simon, who had previously worked with another Canadian folk star, Gordon Lightfoot, they began recording at A&R Studios in Manhattan in early 1968. The initial sessions yielded Tears of Rage, Chest Fever, We Can Talk, This Wheel’s On Fire and The Weight, two of which were co-written by Bob Dylan, and, gradually, they adopted a new name: once Bob Dylan’s band, they now became simply The Band.

Music from Big Pink, the Band’s debut album, was released in July 1968. It had been recorded quickly and straightforwardly, with no overdubbing; Simon had asked the Band what they wanted the record to sound like, and the response had been “Just like it did in the basement”. While it was only a modest commercial success, its critical influence was profound. Al Kooper, writing in Rolling Stone, pronounced:

This album was recorded in approximately two weeks. There are people who will work their lives away in vain and not touch it.

Eric Clapton was so affected by Music from Big Pink’s laid-back authenticity and musical roots that he left Cream, the supergroup he had formed two years before with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, and explored new styles, initially as Derek and the Dominoes and then purely as a solo artist. Roger Waters hailed it as the “most influential record in the history of rock and roll” after the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and claimed that it “affected Pink Floyd deeply, deeply, deeply”; George Harrison admired the camaraderie and musicianship of the Band.

“A passport back to America”

For me, Music from Big Pink has to be considered as half of an informal diptych with The Band, the group’s second album released in September 1969. If the former had unleashed memorable tracks like The Weight and I Shall Be Released, the latter was an even more thoroughgoing exploration of Americana, deeply influenced by Helm’s Southern roots and still-significant memories of the Civil War, by then a century distant. In a 1997 documentary, Robbie Robertson recalls Levon Helm’s father remarking in passing “The South will rise again,” and he was fascinated by the deep attachment to history and mythology which seemed in the ether below the Mason-Dixon line.

The last years of the 1960s saw an explosion and a fragmentation of popular music, with artists tearing off in a dozen directions: Pink Floyd launched into sprawling, messy, introverted psychedelia, Fleetwood Mac began to tack away from their blues roots into more mainstream rock, Joni Mitchell was adding texture and depth to her acoustic folk and the Beatles simply stopped, having changed the face of modern popular music. One genre which was drawing increasing interest was, for want of a better word, Americana: the tradition folk, country and bluegrass music of white America.

The Byrds made early headway. When 21-year-old Gram Parsons joined the band’s ever-shifting line-up in early 1968, he brought a renewed country sensibility which heavily influenced their next album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, recorded in Nashville, Tennessee. It was the first genuinely successful country rock album, followed within months by Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, but before it had even been released, Parsons had left the Byrds and was forging deeper into country music with the Flying Burrito Brothers. The following album, Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde, remained substantially in Parsons’s musical debt.

They were far from alone. At the turn of 1967/68, the Golliwogs, a group of Californian musicians who venerated the music of the South, renamed themselves Creedence Clearwater Revival and within two years had released four albums: a self-titled debut was followed by Bayou Country, Green River and Willy and the Poor Boys, all in 1969. The young Linda Ronstadt, from an Arizona pioneer family, briefly fronted a folk-rock trio called the Stone Poneys then went solo, her first album, Hand Sown… Home Grown an astonishingly polished alternative country record. The Everly Brothers, who had found success with close harmony rock and roll, rediscovered their Tennessee heritage with Roots (1968).

The Band’s pair of albums, Music from Big Pink and The Band, were part of this milieu, of course, but they were much more besides. Perhaps, as four of the five members were Canadians, they had the profound insight which only outsiders are granted. There was something potent, too, in the intensity of their characters and talent.

Robbie Robertson was a flamboyantly gifted guitarist as well as a first-class songwriter, but he was also deeply interested in cinema and influenced by the imagery of Luis Buñuel. Richard Manuel, whose falsetto marked out so many of the Band’s songs, was a nervous introvert who became addicted to alcohol and heroin (he would take his own life in 1986, aged just 42).

Garth Hudson, those critical few years older than his bandmates, was gloriously freewheeling and individual: his innovative use of the organ, which he used to play in his uncle’s funeral parlour, began as a completely distinctive sound but would gradually bleed into popular music over the decades. His air of detachment, looking out from behind a bushy beard with an expression of benign bafflement, was symbolic, but he simply ploughed his own furrow.

Those two albums went to the heart of country, folk and bluegrass with a sharpness and profundity all of their own. The critic and writer Greil Marcus said of The Band that “it felt like a passport back to America for people who’d become so estranged from their own country that they felt like foreigners, even when they were in it”. There is a lot to unpack in that sinuous sentence, but it sums up the importance of the Band’s work. They were, in a sense, not only making new music but also engaging in cultural archaeology, recovering a sensibility that had been lost and forgotten.

Giants of Americana

This legacy is sometimes beneath the surface of popular music, but it endures. Without Music from Big Pink and especially The Band, it is hard to imagine the folk- and country-influenced rock and pop of the 1970s: James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Gram Parsons’s muse Emmylou Harris, the Bellamy Brothers, the Doobie Brothers, Steve Earle, Poco, the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band and, looming over them all in commercial terms, the Eagles, whose original four members had been Linda Ronstadt’s backing band.

Established artists who delved into Americana, like Dylan, the Rolling Stones, George Harrison and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young knew the Band’s work and revered it. Even later mainstream country artists who might initially think of themselves as umbilically connected to the Grand Ole Opry, like Garth Brooks, Tim McGraw and Travis Tritt, felt the tremors of their influence; so too have crossover artists like Hootie and the Blowfish and the Dixie Chicks. The Band did not invent Americana but they set up hugely significant early milestones.

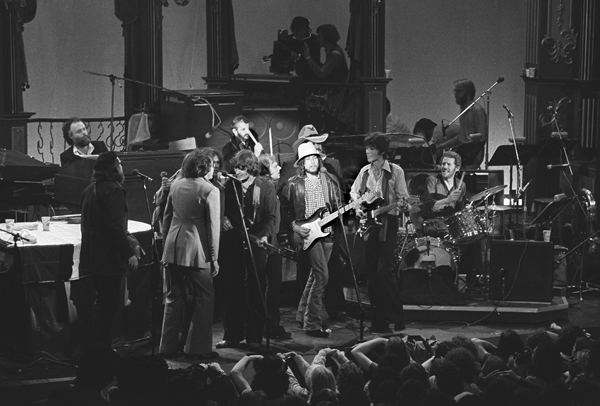

As a discrete unit, their life was brief. There were five more studio albums, Stage Fright, Cahoots, Moondog Matinee, Northern Lights–Southern Cross and Islands, but on 25 November 1976, Thanksgiving Day, they played what they billed as their “farewell concert appearance” at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. They were joined by a number of special guests, and the list underscores just how potent the Band’s legacy and influence were: Eric Clapton, Neil Diamond, Dr John, Bob Dylan, Emmlyou Harris, Ronnie Hawkins, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Ringo Starr, Muddy Waters, Ronnie Wood, Stephen Stills, Neil Young, the Staple Singers.

As if that were not enough, the event was filmed and turned into a feature-length documentary, The Last Waltz, by Martin Scorsese, released in April 1978. Michael Wilmington, writing in The Chicago Tribune, called it “the greatest rock concert movie ever made—and maybe the best rock movie, period”, and a 2020 review in Rolling Stone was headlined “Why The Band’s ‘The Last Waltz’ is the greatest concert movie of all time”.

There would be desultory reunion attempts in the decades which followed The Last Waltz, but the Band’s moment had passed. Manuel took his life in 1986, while Rick Danko died in 1999, aged only 55. Levon Helm died in 2012, then Robbie Robertson, at 80, died in 2023. Now Garth Hudson, the oldest member of the group, is the last to go.

The rock and roll scene of early 1960s Toronto was not an obvious starting point for a collection of musicians who would do so much to create modern American roots music, nor was it predictable that it would be four Canadians and an Arkansan who would do so. But then, nothing was straightforward about the Band. They made music because they could and because they had to, something impelled them to create, in a dazzling variety of ways. They could not have been designed or contrived.

Go and watch The Last Waltz. It is not a collection of the best performances of every one of their songs, but it is a perfect encapsulation of a creative force that was immense and profoundly respected by peers and critics. It is a strange, chaotic, buzzing headache of a film, in some ways, but that, too, is true to their nature. It is also a gallop through the history of American music. Not just a band. The Band.