Lunch is almost a binary meal. At one extreme, the pressures of modern living have reduced it to its bare essentials, merely a pause to take on fuel for the next part of the day, frills and expense at a minimum. It is often consumed — ‘eaten’ seems too luxurious a word — standing up, or at one’s place of work; bites snatched between continued tasks, speed an essential component.

There is another lunch. The extended, relaxed, convivial meal which begins not long after noon and ends… well, it ends when it ends. One of the joys of this kind of lunch is that, from hors d’oeuvres to digestifs, it retains a sparkle, a shimmer of possibility. Even after a dedicatedly sybaritic episode, a good chunk of the day will remain. One can nap and recharge the batteries, or refill a glass and reinforce oneself that way. There is always another adventure to be had.

My dream lunch guest would certainly have opted for the second kind. His career was marked by indulgence as much as it was by talent, and his reputation grew and grew with every passing year. Of course, things were different then, behaviour once routine now unprofessional at best: but L.P. Hartley was quite right about the past being ‘a foreign country’.

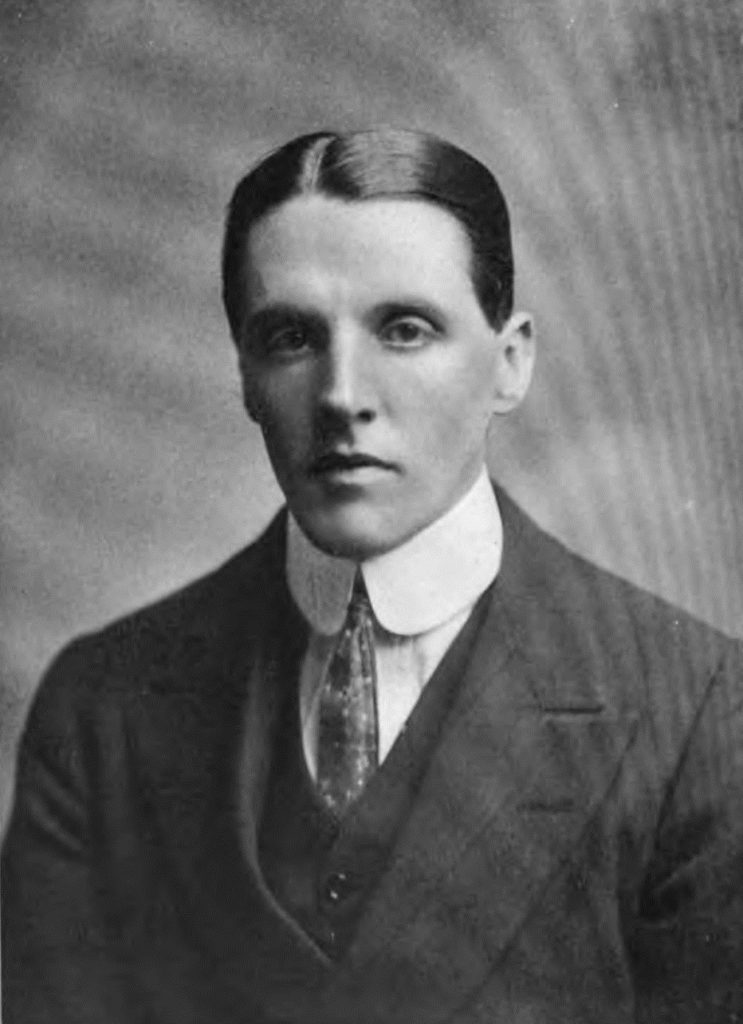

Frederick Edwin Smith, always known as ‘F.E.’, was born in Birkenhead, improbably enough, in 1872, the year of the first FA Cup Final, and also the year in which Monet began painting the first work of Impressionism. F.E. was to become a brilliant barrister, a stinging wit and a precocious Conservative Member of Parliament, and seemed destined for the very top until, in 1919, he was appointed the youngest lord chancellor since Baron Jeffreys in the 17th century. Although a unique and distinguished office, his placing in the House of Lords cut him out of the business of government that happens in the House of Commons; as a peer, he recognised he would never be prime minister, and boredom set in.

A man of constitution

When F.E. was bored, he drank. It was recorded by Neville Chamberlain that he was passed over for a second stint as lord chancellor in 1928 for fear he might be seen drunk in the street. Two years later, he was dead, of pneumonia brought on by cirrhosis of the liver. As one of the royal physicians had predicted, “Mentally, he’s a colossus. But he’ll tear himself to pieces by the time he’s sixty.”

Why F.E.? He was sharp as a razor. At Oxford he traded verbal blows with Hilaire Belloc and dominated the Union, while picking up a First in law. The courts were a natural theatre for his very precise, English wit. When a judge told him wearily, “I have listened to you for an hour and I am none the wiser”, he replied, with a smile: “perhaps not, my lord, but far better informed”.

Another member of the judiciary unwisely and pompously asked F.E. what he thought he was on the bench for. “It is not for me, Your Honour,” he answered, “to attempt to fathom the inscrutable workings of Providence.”

Moreover unlike many great wits, F.E. was clubbable rather than a bore. With Winston Churchill, he founded the Other Club in 1911, a dining society for prominent politicians and others. Smith largely wrote the rules of the club, which summed up him and his circle. Rule 2 was simple: “The object of the Other Club is to dine.” But Rule 10 gave a sense of how seriously the members conducted themselves: “The names of the Executive Committee shall be wrapped in impenetrable mystery.”

So a lunch with F.E. it will be, and a good lunch. Assuming I can suspend my avoidance of alcohol, we will start with cocktails at the Donovan Bar in Brown’s Hotel. The modernism of the surroundings may shock my guest, but a dry martini will reassure him that all is well. And a single martini is an abomination, so we shall have another round. Indeed, it may have been F.E. who first remarked that martinis are like breasts: one is never enough, and three is too many.

Thereafter we could go to the Savoy Hotel, the original home of the Other Club; I suspect F.E. would also be at home in Rules in Covent Garden, with its Edwardian booths and plush velvet. But I cannot let the great man have it all his own way, so we will go to the Boisdale in Belgravia, run by the fabulously louche and sophisticated Ranald MacDonald (whom I think F.E. would have liked). There is plenty of red meat here for us, including cuts of exquisite Buccleuch beef, and a comfortingly long wine list (though F.E. would need a bit of guidance through some of the more far-flung offerings from New Zealand and California). He would know what to do with a Gevrey-Chambertin or a Pétrus.

I have questions for my guest. Why was he seemingly drawn to causes which would eventually seriously unfavour him? What drew him to the people of Ulster, and a reckless attachment to their rights which verged on seditious? Why did he devote so much energy to opposing the disestablishment of the Church in Wales? More than that, though, I want to know what the Edwardian Bar was like, by then at its height of fame and frequented by some of the greatest advocates. Smith was one of the best of them all and one of the best paid. By the eve of the First World War, he was earning £10,000 a year, nearly £2 million in today’s money.

After lunch we will certainly want a cigar on the terrace. What Edwardian gentleman would not? I would ask him why he took the lord chancellorship in 1919, knowing it would end his front-rank political career. Did he have some premonition that he was not destined to make old bones? I want to hear him talk about ambition. His own was frank and aimed high. He announced at the age of ten that he would be lord chancellor, and so he eventually was. His career path was carefully planned: a dazzling speaker in the law courts, earning (and spending) huge amounts, then into the House of Commons with a monster of a maiden speech, described as the most accomplished ever.

When I think of F.E. I think of the extended lines of a Spy or Punch cartoon, the lean figure bending forward to hector or persuade, the long face and black hair almost demonic. There is a sense of the energy burning off F.E., like some kind of electrical current. He has been filled with the power of destiny, but he cannot contain it forever.

“Was it all worth it?” I will eventually ask as we smoke our coronas and regard the skyline. A smile on those sometimes-pursed lips. A spark in the eyes.

“I rather think so. Don’t you?”